In the Introduction to Section 3, we provided a link to the Communication Program at UCSD. We identified the Communication Program as one of the critically needed resources that LCHC could draw upon in seeking to make its new home. As we begin to describe the program of research and theory that occurred between the mid 1980s and roughly the turn of the century, we will also elaborate on how the Communication Program developed into a Department and the ways it influenced, and was influenced by, LCHC.

Upon LCHC’s arrival at UCSD, the Communication Program was under intense pressure to reform itself or be disbanded. Student numbers had grown out of proportion to faculty available to keep the Program afloat, never mind reform itself. Owing to the internal dynamics of UCSD, reform was the path chosen. This choice required the curriculum to be thoroughly revised in order to make it intellectually coherent, and it required the hiring of additional faculty in order to be able to carry out the redesigned curriculum. These changes needed to happen very quickly – at the time, only 3 ½ regular faculty positions, including Mike’s, were allotted to the Program, which was responsible for educating more than 300 majors. These numbers were far beyond the limits of campus norms.

Consequently, as a part of the arrangements that made it possible to move the Lab from New York to San Diego, a small number of temporary faculty positions were made available as a “starter kit.” Arrangements were made for members of LCHC to occupy those temporary positions, often splitting teaching and research time to create a full time position with the potential for them to compete for positions that we hoped would open up if the reforms to the program were successful. Hence, most of the key personnel in the Lab also participated as instructors in the Communication Program. The resulting cross-pollination of ideas across several academic disciplines proved beneficial to both the Program and to LCHC.

The curriculum that was in place when we arrived at UCSD was divided into three areas designated as “macro,” “micro,” and “media.” Sociologists and political economists filled the former two categories, and a documentary filmmaker filled the latter. That organization was a convenient fit for the faculty already at UCSD who were teaching in the Communication Program, but it did not at all fit the notion of communication that we arrived with.

Based on LCHC’s developing understanding of communication as a form of joint mediated activity embodied in cultural practices, including our studies of the psychological and social consequences of literacy using this approach, we proposed a different tripartite division of the curriculum that was represented by a generalized semiotic model. We referred to these parts as “Communication and the Individual,” “Communication and Culture,” and “Communication as a Social Force.”

This overall conceptual schema provided a perfect fit to the institutional organization of UCSD, which relied upon a three quarter system. Simultaneously, it mapped directly onto what we were coming to understand as a cultural historical activity theory. We proposed a “spiral curriculum,” beginning with an introductory course that encompassed all of the media developed from the appearance of cave art to the emerging new forms of digitalization. This introduction was then divided into three courses corresponding to the three constituent perspectives (the person, the cultural medium, the political-social-economic order) and continued with specialized courses including “media methods” courses that allowed students to put theory into practice in a variety of ways. An “integrative seminar” that brought the various parts of student experience together completed the curriculum. The activities that fell under the previous category of media, which in principle had meant video film making, were integrated into the category called “media methods.” These courses were re-conceived as theory-practice courses in which students engaged in some form of communicative practice ranging across all of the media, including oral and written language, radio, film, theatre, television, and that “new medium,” the digital computer.

This curriculum implemented by a combination of faculty who were present when LCHC arrived, members of the Lab, and a few additional temporary faculty began to function in the spring of 1979. Still understaffed, but not so understaffed that an effective education was impossible, the new “triangular” curriculum went into effect with the blessing of the campus administration. The students kept coming, and the curriculum had been rendered intellectually acceptable to the relevant faculty committees.

At this juncture, a new problem presented itself. Again, by virtue of established campus practices, programs could not hire tenure track faculty. Such faculty could only be hired in Departments and then shared with the program. Fifty-fifty was the basic model – half teaching in one’s department and half in the program. This seemed to be a wise policy assuming that the program was small – an interdisciplinary effort which departments could contribute to at no particular expense. However, the Communication program was so large that even it would required an addition of approximately 20 tenure track faculty members, only half of whose teaching could be in the program, to bring the teaching ratios up to University-wide norms.

As a purely practical matter, the contradiction between very high student demand and glaringly high faculty-student ratios meant that something had to be done to allow the system to function effectively.

In principle, it would have been possible to appoint a succession of three-year temporary instructor positions, but that route conflicted with the notion that the program should arise from the interests of faculty in established, disciplinary departments, where standards of excellence were carefully guarded. Even after the new curriculum was in place, campus committees were convinced that the Program could not attract scholars acceptable to existing departments. That illusion was shattered rather quickly. Within three years, three scholars accepted, and even welcomed, positions at UCSD to be in the Communication Program.

Having allowed the Communication Program to grow in numbers to the point where it had to be fixed up or closed down, and having learned that the ideas underlying the curriculum attracted first-rate scholars who wanted to engage with issues of communication, the University began to take seriously the repeated calls to convert the Communication Program into a Communication Department.

A more detailed account of these events can be found by following the Communication Program link. However, with respect to LCHC, these changes meant that additional faculty dedicated to Communication could be hired and that perhaps 1/3-1/4 of these people would share the Lab’s general orientation to this nascent discipline, hence serving both institutional entities simultaneously.

LCHC’s New Faculty and Their Scholarly Programs

The Communication Program, which had become a Communication Department in 1982, played an important role in the process of LCHC’s development. Not all of the changes were happy ones: none of the LCHC faculty who had carried a heavy load in stabilizing the program in a manner that allowed it to become a department were deemed worthy of continued employment on tenure track lines. These losses clearly damaged our ability to work in ethnically diverse communities and continue our training program focused on such work. At the same time, however, it made it possible to attract outstanding scholars who greatly expanded and enriched LCHC’s research program.

Carol Padden & Tom Humphries

In 1983, the Communication Department hired Carol Padden, a Deaf linguist who specialized in the study of sign language and culture. She and her husband, Tom Humphries, whose work at the time was focused on the higher education of deaf students at a nearby college, joined LCHC. Their presence brought a completely new dimension of diversity to the Lab, including a new set of and concerns about inequality to add to the portfolio of the Lab’s concerns.

Tom Humphries

Carol’s doctoral research focused on the long-standing question of whether or not American Sign Language (ASL) is a fully formed language in the same sense that the world’s oral languages are fully formed. For many, the phrase “deafandum” was the reigning belief.

An important result came out of Carol’s thesis research that was a surprise to many scholars at the time — ASL includes the sign/movement equivalents of phonemes (sounds) in oral languages. Moreover, these sign phonemes obey rules in the same ways that phonemes do in spoken language. Here is how Carol and her colleague David Perlmutter (1987) summarized this basic result:

“Sign language phonology provides novel support for generative phonology. Without explicit rules and grammars, one would focus on sounds and signs themselves – entities so different that the commonality of oral and signed languages would go undiscovered. Once the rules that account for the lexical and phonological structure of ASL are discovered, however, it is striking that they interact in ways predicted by the theory [that accounts for the analogous patterns in spoken language – MC].”

The strong conclusion from this research, which is currently common wisdom, was that ASL is a full-fledged language.

Satisfied that proof of the linguistic status of ASL had been established, Carol then addressed a troubling fact about the development of deaf children: they generally fared poorly in schools. One of her first projects was to study a large sample of deaf children attending either a residential school for the deaf or a special education classroom for deaf children in a public school (Padden, 1993; Padden & Ramsey, 1997; Padden & Ramsey, 1998).

Padden and her colleague Claire Ramsey confirmed a major, but poorly understood, finding in the field — deaf children of deaf parents were better readers and writers of English than deaf children of hearing parents. Something about the way that deaf parents communicated with their children helped those children when they encountered the need to read and write in English at school. An obvious potential explanatory factor was that the children had acquired ASL. Nevertheless, this hypothesis still raised questions about how deaf children could learn to read and write an oral language in a writing system that represents an oral language, particularly considering that such children could not hear and that their language could be considered as different from spoken English as Russian or Chinese.

Some idea of how teachers seek to arrange for deaf children to acquire literacy in English was provided by observing the teachers and their pupils in regular classroom lessons and in specially arranged tasks that called on the children who had acquired ASL to “read aloud” in sign.

On the basis of their observations, Padden and Ramsey (1997), reported that:

“Chaining is a technique used by some teachers to form a relationship between a sign, a printed word, and a finger spelled word or sometimes all of them together. In this technique, a teacher might, for example, fingerspell a word, then immediately point to the same word printed on the blackboard, and fingerspell the word again. Or, a teacher might produce a sign and then fingerspell its English translation immediately after. This technique seems to be a process for emphasizing, highlighting, objectifying and generally calling attention to equivalences across texts and languages” (1997, p. 6).

It is easy to see how, from this description, knowledge of ASL is critical to children establishing the relationship between the signing and the acquisition of literacy. Without such knowledge, the children would have nothing to map finger spelling or printed English words on to. Understanding how deaf children who know ASL read and write English is still a challenge to researchers (See Mayberry et al., 2011).

More…

This line of research, focused as it is on individual children in school situations, provided lot of important information about life factors associated with literacy achievement. However, it left relatively unanalyzed the persistent finding that deaf children of deaf parents consistently outperformed children who acquired ASL outside of the family. To understand how this kind of family advantage is created, it is necessary to step outside of the classroom seen through the lens of instructional routines and to consider a complex web that included the experiences of children with significant hearing loss. This meant going outside of the classroom and into the lived reality of deaf people.

The everyday lives of hearing-impaired people was the focus of work carried out jointly by Carol and Tom in 1984, which resulted in the publication of Deaf in America. Their book explained why it is important to understand the existence and nature of Deaf Culture, which they argued should be understood in the same way that cultural anthropologists traditionally use the term culture. Carol and Tom explain the logic of their approach in the introduction to a book they wrote many years later, when broad acceptance of the notion of Deaf Culture had become prominent:

“Following James Woodward’s example, we adopted the convention of using the capitalized “Deaf “ to describe the cultural practices of a group within a group. We used the lower case “deaf” to refer to the condition of deafness, or the larger group of people of individuals with hearing loss without reference to this particular culture… (Inside Deaf Culture, 2005, p. 1).”

Carol and Tom hoped to be “agents of a changing discourse and consciousness” (p. 2) and used the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” in order to describe a culture a group of people who, as they put it, “did not have any distinctive religion, clothing, or diet – or even inhabit a particular geographic space they called their own” (p. 1).

In their reflections on this period of work, Carol and Tom provide an unusually clear statement of interconnection between this work and LCHC’s traditional concerns about diversity and inequality. They pose the question, “How can two conflicting impulses exist at the same time – to eradicate deafness and yet celebrate its most illustrious consequence, the creation and maintenance of a unique form of human language?” Then they generalize this question as one example of a wide variety of cases:

“This conflict of impulses, to “repair” on the one hand, and to acknowledge diversity on the other, must be one of the deepest contradictions of the twenty-first century. Deaf people, whether they like it or not, live their lives in the middle of this contradiction. They share their predicament with disabled and ethnic groups …” (p. 165).

In conjunction with the other people who gathered at LCHC during this decade, these common concerns generated a myriad of productive collaborations among LCHC members and the Communication Department.

Jim Wertsch

Jim Wertsch had a long history of involvement with LCHC that extended back to connections and collaborations during and after the time that Jim was a post-doctoral fellow in Moscow. Officially located at the Pushkin Russian Language Institute, a part of Alexei Aleivich Leontiev’s research group, Jim also spent considerable time studying with Alexander Luria and Vladimir Zinchenko. All of these associations, combined with Jim’s careful reading of the full range of extant Vygotsky texts, made him a “bridge figure” in creating continuity between the early generation of non-Russian scholars attracted by Vygotskian ideas and the next generation of scholars who followed in that tradition. This aspect of his work has taken on renewed interest in light of a subsequent decades-long debate between those who associate themselves with Alexei N. Leontiev’s interpretation of Vygotsky as an activity theorist and those who oppose that “continuity” view and champion Vygotsky’s “cultural historical” approach as distinct from activity theory.

Jim Wertsch

The major lines of work that Jim published in the 1980s and early 1990s establish the outlines of the disagreement among Vygotsky’s followers and Jim’s early attempts to introduce Bakhtin into the discussion as a means of enlarging on Vygotsky’s proposals for a materialist psychology.

To make the architecture of the discussion clear, we begin with his publication of an edited volume in 1981, The Soviet Theory of Activity. This volume laid out the case for continuity, as it was formulated by the time by Alexei N. Leontiev and his followers. It provided the American community interested in the fate of Vygotsky’s ideas in the U.S.S.R its first overall look at the branch of Vygotsky’s legacy that became closely associated with activity theory. It was here that one found a concise statement by Leontiev of his overall approach, the application of that approach by Vladimir Zinchenko and colleagues to the analysis of movement, and a series of articles articulating the theory and providing empirical examples of its use.

In 1985 Jim published Vygotsky and the Social Formation of Mind, which was the first synthetic presentation of many key Vygotsky writings for an English speaking audience. His treatment included the way in which the basic ideas were tested and appropriated by developmental and cross-cultural psychologists, including the research program of LCHC. It also included a prescient discussion of what the notion of activity would entail if it were to be integrated with Vygotsky’s approach. Put as succinctly as possible, Jim’s proposal, which coincided in many respects with the approach adopted by Zinchenko, was to modify Vygotsky’s focus on word meaning as the basic unit of analysis for the study of consciousness to the unit of mediated action:

“The analytic level in Leontiev’s theory concerned with action fulfills Vygotsky’s requirement that a unit be applicable to interpsychological as well as intrapsychological functioning. It is also compatible with Vygotksy’s account of mediation…The analytic unit of action avoids the shortcomings of word meaning while preserving its strengths” (p. 208).

In this same monograph, Jim addressed questions of context and mediation of interest to the Lab dating back to its involvement in cross-cultural research. In particular, with respect to the issue of culture and context specificity, he argued that a central role in transfer is played by the “decontextualization of meditational means,” while staunchly contending that to think of a “context free” mediated action is a contradiction in terms.

The last chapter of this monograph can be viewed as a kind of introduction to his next book, Voices of the Mind, published in 1991. The focus of the final chapter is on the decontextualization of meditational means in order to relate psychological processes (mediated action) to social institutions. In developing this line of thought, he focused in particular on the work of Bakhtin. He wrote, “Unlike Vygotsky, who provided only the general outline of an account of contextualized significance, Bakhtin endeavored to understand “language in its concrete living totality” (p. 225). The similarity between Jim’s concerns and the interests of both LCHC and the Communication Department should be clear just from the summary of these books.

While he was at UCSD, Jim’s interest in forms of semiotic mediation, reaching as it did beyond dyadic conversation into discourse, made him an active participant in ongoing academic work at UCSD focused on nuclear discourse. This interest brought him into interaction with a broad range of social scientists at UCSD concerned with the issue of “mutually assured destruction” and into the arena of cultural memory, topics that were latent in the line of sociocultural studies that he helped to create. These efforts brought the Lab into close contact with colleagues in Southern Europe and Latin American with whom exchanges were initiated and collaborations begun. It was a heavy blow to LCHC when Jim and his family moved back to the mid-west.

David Bakhurst

Bakhurst

Luckily for the Lab, David Bakhurst arrived at LCHC shortly after Jim left. His arrival helped to maintain (as well as to broaden in new directions) the Lab’s interest in Vygotskian theory. In a sense, Jim had created a link to his and David’s interests. In developing his argument about action as a unit of analysis for the study of consciousness, Jim referred to the work of Evald Il’enkov. Ilyenkov himself pointed back to Spinoza, which coincided with Vygotsky’s interest in Spinoza, highlighting the anti-dualism of Vygotsky’s enterprise. Their point of convergence was human action, “caught in the act” – as moment of performance.

David, too, had a prior history with LCHC. In 1983, when the Coles were in Moscow in connection with exchange activities (See Chapter 10), they also attended lectures that David gave as part of a clandestine seminar at the Institute of General and Pedagogical Psychology organized by Felix Mikhailov.

The topic of his lectures was philosophical issues central to the Soviet philosophers and psychologists such as the nature of personhood and the sociocultural origins of ideality. David’s work deepened our understanding of long standing controversies in anti-dualist, Western philosophy. One of the seminars was transcribed, translated, and published d in Studies in East European Thought.

The focus of David’s own work was Ilyenkov, who we soon learned, had “been adopted,” in David’s terms, by the circle of Vygotskian psychologists led by Vasilli Davydov and Vladimir Zinchenko. Like Mikhailov, Ilyenkovtook a special interest in the development of blind/deaf children, for whom a special educational program had been worked out by other psychologists inspired by Vygotsky (see, Meshcheryakov and Levitin). This combined interest in developing a materialist, anti-reductionist philosophy of human consciousness in conjunction with an “applied program” designed to promote the development of the blind/deaf created an immediate point of contact between David’s interests and those of Carol and Tom.

Because of LCHC’s involvement in Soviet-American exchange activities through both Mike and David, Mikhailov and a blind/deaf psychologist, Alexander Suvorov, came to UCSD so that speakers of two very different forms of sign language could communicate with each other. Carol and David subsequently wrote about this line of work together, The Meshcheryakov experiment: Soviet work on the education of blind-deaf children (see also, this summary).

We can best capture the attractiveness of David’s interpretations of, and elaborations upon, the work of Ilyenkov for our attempts to understand the relationship between mediation and activity, by quoting liberally from the talk that obtained him a job at the Communication Department.

A central question David (1988) posed in seeking an alternative to Cartesian dualism via Ilyenkov was “How do material objects acquire the ideal properties which make them suitable objects of thought and experience?” The short answer, provided by Ilyenkov, is that objects acquire ideal properties by virtue of their incorporation into human, culturally organized, social practices:

“Ideality is rather like a stamp impressed on the substance of nature by social human life activity; it is the form of the functioning of a physical thing in the process of social human life activity” (Ilyenkov lchcautobiod in Bakhurst, 1988, p. 37).

David (1988) explains this idea, following Ilyenkov, with the example of a pen:

“And it is to this “ideal form,” impressed upon nature by human activity, to which the objects of the natural world owe their status as possible objects of thought … The pen is certainly a material thing, But how do we distinguish this thing’s being a pen from its being a lump of material stuff? … What would an account of this object in purely physical terms fail to capture? Ilyenkov would say that the object exists as an artifact in virtue of a certain social significance, or meaning with which its physical form has been endowed, and it is this fact which would be lost in any purely physical description. It is this significance which constitutes the object’s “ideal form.” Where does it get its significance? In the case of the pen the answer seems clear: the fact that it has been created for specific purposes and ends and that, having been so created, it is put to a certain use, or more generally, that it figure in human life activities in certain ways. One might say, with Ilyenkov, that social forms of activity have become objectified in the form of a thing and have just elevated a lump of brute nature into an object with a special sort of meaning” ( p. 37).

David generalizes the example of the pen because for Ilyenkov the transformation illustrated by the pen is “not just an alteration in the physical form of the natural world, but its wholesale idealization of it; man transforms nature into a qualitatively different kind of environment.”

These ideas were obviously important for LCHC efforts to understand and develop the line of ideas we associated with Vygotsky and Leontiev. Mike adopted them in his thinking about the design and implementation of the Fifth Dimension (5thD); Don Norman took up his own version of these ideas in his work on “cognitive artifacts;” and Yrjö Engeström followed with a discussion of “when is an artifact?”

Crucially, these same ideas were of great interest to colleagues in the Communication Department. David concluded his talk by pointing out that Ilyenkov’s ideas, which were so attractive to our Russian colleagues, also provided an “innovative and distinctive” model for the study of Communication. It follows from Ilyenkov’s ideas, he argued, that:

“…the study of mind, of culture, and of language (in all of its diversity) are internally related: that is, it will be impossible to render any one of these domains intelligible without essential reference to the others. But if that is so, then it won’t just be a good idea to combine the study of psychology, sociology, and language, it will be absolutely imperative to do so. The development of an interdiscipline which seeks to grasp mind, culture, and language in their internal relations will be essential if we are to understand the human condition” (Bakhurst, 1988, p. 39).

Yrjö Engeström

As in the case of Jim Wertsch and David Bakhurst, LCHC’s involvement with Yrjö Engeström began several years before his arrival and was closely connected with contemporary research flowing from the Vygotskian tradition. Mike and Yrjö met in 1984 at an Activity Theory Conference in Utrecht hosted by an early precursor of The International Society of Cultural-historical Activity Research.

Immediately recognizing their mutual interests, they initiated a series of visits and began to make each other’s work known among their regional colleagues. From LCHC’s perspective, Yrjö was a scholar who was deeply immersed in developing Leontiev’s approach to activity theory, which he treated as a complement to Vygotsky’s work not as an opposing scientific and ethical program of research. Where Jim had brought us news of the “activity turn” in Soviet psychology carried out by Leontiev and his disciples and had discussed the sorts of modifications in Leontiev’s ideas that would be needed for it to be consistent with Vygotsky’s ideas, Yrjö created an entire research program pursuing his proposal for a consistent theoretical framework.

An extended version of Yrjö’s talk when he came to visit LCHC in 1985 was soon published in our Newsletter. Drawing heavily upon material that would appear in Learning by Expanding,

his talk addressed many of the key theoretical and methodological concerns that swirled around the Vygotskian legacies worldwide. A few selections from that paper provide a clear picture of why Yrjö’s work fit so well with the Lab’s concerns and efforts to combine mediation and activity in our theory and practice of research on learning and development.

First, he argued that resolution of a variety of critical issues in developmental psychology (he chose the relation between learning and development as one example, the relation between individual and society as the other) could not be attained unless a third, mediating factor were introduced into the binary relation under consideration. For him that third factor was activity. To us, human activity in general and particular systems of activities are culturally organized. Developing the activity/culture/context relationship in our theorizing about human development was a genuine meeting ground.

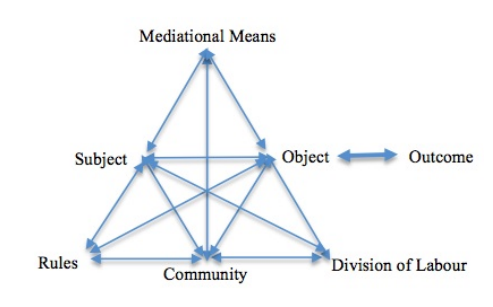

Second, Yrjö introduced his “expanded triangle” in which the subject-mediator-object relationship is expanded to include the community, its division of labor, and its social rules. He argued persuasively that:

“It is essential that human activity cannot be reduced to the upper sub-triangle alone. Human activity is not only individual production. It is simultaneously and inseparably also a social exchange and a social distribution” (p. 26).

Third, Yrjö emphasized the universal tendency among those who concern themselves with children’s development to assume the presence of more knowledgeable, authoritative people organizing individual experience “for” the child or the less capable person – the “top down” constraints on the “bottom up” process of children actively engaging their worlds. This orientation, he argued, obscured the need to understand how the new is generated from the old. It also left psychologists without anything to say about societal development. Eschewing the idea that there is a great leader who can serve as the vanguard and teacher of the masses, developmental psychologists, and activity theorists as well, were left impotent to address ongoing issues of social concern in a coherent manner. So when Yrjö spoke of a zone of proximal development, he was challenging the field and society to create ways to be active agents in their own development.

All of these points resonated strongly with LCHC’s traditions, biases built into its organization. The cultural mediation of development was, for, us the essential third factor in this form of anti-Cartesianism. Culture was understood not as a static structure of meanings, but a material process that is historical at its roots. Any methodology designed to study it must study activity systems over time. Yrjo’s emphasis on discoordinations as symptoms of underlying systemic processes fit perfectly with the way in which we had come to understand the process of reading acquisition.

Yrjo’s third emphasis posed an un-resolved question. How are we to understand the process of development? Zones of proximal development were difficult enough to arrange for given our ability to create conditions to be able to show how children actively appropriate (not copy) the given. But how does newness, qualitatively new ways of being human beings, come into the world? The only way we were going to find out was to try to implement our theoretical claims in new modes of social practice and try them out. The answer in both LCHC’s case and in Yrjo’s program of research, was to include theory-driven efforts to change the situation – e.g., some form of intervention research (see Engeström’s Selected Publications).

During the years he spent at LCHC, Yrjö was deeply involved, both in California and in Finland, in developing a nascent program of research into adult work activity that he and his colleagues referred to as “Developmental Work Research (DWR).” Yrjö characterized this approach in the following terms:

“There are three theoretical and methodological ideas that characterize developmental work research. First, the unit of analysis is a collective, object-oriented activity system, mediated by artifacts, community forms, division of labor, and rules. Individual actions and situations, as well as failures, disturbances and innovations, are analyzed against the framework of the entire activity system…

Secondly, causes of disturbances, innovations and change are seen in deep-seated contradictions within the activity system. Contradictions are identified through analyses of the dilemmas, conflicts and discoordinations that manifest them in everyday practice, both historically and in the present. Qualitative changes in the activity involve resolutions of the contradictions, leading to the formation of novel ones…

Thirdly, change and development are studied as long-term collective learning processes. They often lead to the local expansive construction of new artifacts and new models of shared practice, not just to new cognitive structures within the minds of individual subjects” (1991, p. 78).

The cleaning study and its progeny

The prototype of DWR was Yrjö and Ritva Engeström’s study of the work of office cleaners and their trainers in Finland. The idea was to expand beyond “training” in adult education to emphasize contexts of learning and development. They analyzed the varying histories and perspectives of all the participants through participant observation at work, interviews, videotaping specific cleaning tasks performed, and simulated recall interviews of those videotapes.

This project included accounts of cleaning work over historical time taken from written narratives and textbooks on cleaning. The historical data suggested the existence of conflicting models of this form of work. One was “a model of home cleaning” (with competencies presumed to be acquired by housewives), and the other was a “model of rationalized cleaning work” (competencies of wage laborers with minimal specific training). Neither model appeared adequate for the work required to clean offices. While the new approach did not take hold in that company, as Ritva notes, the lasting impact was to be found as a demonstration of the approach and in the response of participants who found this new emphasis on learning transportable to other employment.

The “cleaners research” served as a prototype for a series of studies that compared Finnish and American practices in a variety of institutional settings. The projects focused on problems emerging in and around organizational changes in health care and in courtrooms. In one of their publications, the Engeström group studied the mechanisms of organizational forgetting as part of the change process. One of their examples was a urology clinic in which there was no formal mechanism for providing the workers with the clinic’s history. Current workers had no sense of the larger history of their own work. They only had access to artifacts, records, and histories about the clinic directors and the organizational plant. Histories relevant to patients and staff were not preserved among the memorabilia. A number of studies that elaborated different parts of the analytic scheme in different circumstances filled out the larger DWR agenda.

Yrjö undertook another multi-site research project in the early 1990s that compared Finnish and U.S. settings with colleagues and students in both countries, this time related to the organization and change of courtroom processes. This research continued the focus on looking at the innovations participants use and to make sense of, organize, and cope with challenges in their work – both in spite of and in response to external pressures. In each study, participants’ responses to breakdowns and repairs in the flow of their interactions were analyzed as innovative responses to system pressures that were internal and external to the activity system, pointing both to the sources of those pressures and to possible future forms of their work.

One study focused on changes in the court calendaring process and a delay-reduction program that increased pressures to move proceedings along. In addition, it looked at how judges innovatively manage the subsequent increase in workload. The article showcased one judge and attorney’s joint use of an “issues conference.” This included the judge’s innovation, which was a list of items to be covered such as a conference as tools in an efficient repair strategy to keep court proceedings flowing for example when some aspect of the routine or protocol went awry. The analysis (Engeström, 2005) depicted court proceedings as a:

“[Z]one of proximal development…an invisible battleground. In the ongoing work activity, disturbances occur continuously. Disturbances are dealt with both regressively and expansively. Innovative solutions appear. But innovations may be blocked by ruptures in the intersubjective understanding between the participants of the activity system” (p. 216).

More…

Technology in context

As a final example in this sampling of notable projects during Yrjö’s years at UCSD, we include a study in 1993-4 with student Virginia Escalante on the development and deployment of a new postal kiosk called the “Postal Buddy”. Working with a digital design company, the USPS designed the Postal Buddy, a freestanding electronic kiosk that was supposed to enable immediate, online change of address as well as easy purchase of customized business cards, address labels, and stamps. The manufacturer of the Postal Buddy designed the system to be extremely user friendly and likable, with a touchscreen, instructions spoken by a human voice, and a somewhat human-like external appearance.

The study exemplifies, first, developing understanding of the concept of “an artifact” mentioned earlier in connection with David Bakhurst’s work. Second, the study offers a critique of early work in actor-network theory (offering as an alternative DWR for linking micro and macro level analyses of the development and use of the kiosks). The authors note:

“Connections an exchanges between nodes in a network can be adequately characterized only on the basis of historically grounded understanding of the inner working of the nodes of the network, this requires an articulated conceptual model of the anatomy of an activity system” (DWR 2005 p. 284).

Engeström and Escalante proceed to question both the assumption that that intended end user of the technology as simply one of several nodes an a network and the notion that users use tools “for its own sake” (p. 280). The authors ultimately showed that users were coming to the kiosks with different needs and expectations than imagined for them by the people who authorized and developed the kiosks. Ultimately, postal customers did not find the Buddy appealing, fun, or an acceptable substitute for people (Developmental Work Research, 2005, p. 261-262).

In addition to this main line of research around work activity, Engeström directed the research of a number of graduate students who carried out empirical studies of adult activity, approached from the developmental work orientation with a focus on new forms of communication (bespeaking the strong overlap between Yrjö’s interests and those of the nascent Department of Communication). Each case posed issues of appropriate methods of data collection, the comparison of cognate intellectual movements such as actor network theory, ethnomethodology, or other strands of organizational, communication or education theory (See Brown, 1996; Foot, 1999; Rhyne, 1995; and Sammond, 1999).

This brief summary of the major projects Yrjö carried out at UCSD makes clear his importance both to LCHC and to the Communication Department, where he became a professor in 1988. Eventually the conflicting demands of living on two continents was resolved by the Engeström family moving back to Finland.

David Middleton

When Yrjö was offered a professorship at UCSD in the spring of 1987, he was still heavily entangled in academic life in Helsinki, which required significant reorganization if this research program was to be located Southern California. By good luck, David Middleton was available to teach for a year at UCSD while Yrjö got his affairs together in Finland.

David brought with him enthusiasm for Morris dancing, discursive psychology, and a willingness to engage the cultural historical, activity based approach that was taking shape at UCSD. His influence on LCHC has been a lasting one in making the theoretical and methodological relevance of discursive approaches to psychology to LCHC’s concerns.

One mark of David’s influence on the Communication Department and LCHC was a conference and later a book on social/collective remembering (see also Cole’s preface to the book). The book is an instructive example of what it meant to think about LCHC as a kind of intellectual incubator. David went on to do foundational work in the development of a discursive psychology, enriching our developing version of a Vygotskian-inspired developmental science.

Olga Vasquez

In 1989 Olga Vasquez came to LCHC as a post-doctoral fellow, trained in anthropology and education at Stanford University. Having grown up in a migrant worker family and having taught school before entering graduate school, Olga conducted research using computers in non-school settings, including an ethnographic study of immigrant children who acted as cultural brokers in the process of their development.

Instead of spending one post-doctoral year at LCHC writing up the results of her work and then looking for a job, Olga became intrigued with the research being conducted with the 5thD. A conspicuous shortcoming of the 5thD in the Boys and Girls Club was the failure of Latino community, largely immigrant Mexicano children to participate, despite considerable efforts on part of those who were implementing the program.

Olga set out to create a locally sustainable, community controlled activity setting that would provide optimal conditions for this very important, but very marginalized, population. Fortunately for all concerned, Olga obtained a faculty position in the Communication Department and continued to develop her activity system, La Clase Mágica, using the 5thD as a model. Over subsequent decades, this work has continued to expand (see Chapter 12).

LCHC as an Incubator

It should be clear from the preceding narrative that an extraordinary combination of people participated in the development of this new instantiation of LCHC. It was now a research unit with several full-time faculty members involved, each with their own projects, all of which were now exploring the broad domain of bio-cultural-social-historical activity-grounded theorizing. Moreover, both collectively and individually, we were able to collaborate in a productive manner with other groups of scholars with allied interests at UCSD, further broadening the range of topics that came before us in our collective discussions.

The introduction to a document prepared for the UCSD Administration (1992) succinctly characterizes the intellectual currents that constituted LCHC in a report to the UCSD Administration during this period of LCHC history:

Within psychology, the approach adopted by LCHC is variously referred to as cultural-historical psychology, cultural psychology, or a cultural context approach to psychology. It is distinguished from alternative approaches in psychology by its rejection of the idea that “the mind is in the brain,” treating mind instead as a phenomenon distributed among people and their artifacts, including language and social institutions. This approach is also closely linked to social science movements referred to as ecological psychology and activity theory which ground their analyses in the everyday culturally organized activities of people as well as a variety of social science enterprises which fall within the general rubric of socio-cultural studies.

Because of its emphasis on culturally organized activities as the locus of its theorizing and empirical research, the staff of LCHC has always included scholars representing a variety of social science disciplines, including psychology, sociology, education, linguistics, philosophy, and anthropology (for which “culture” is a foundational concept). At present, for example, the core faculty of LCHC hold degrees in anthropology, education, artificial intelligence, and philosophy. It is also a multi-ethnic, multinational faculty consisting of two Anglo Americans, one Mexicana/Latina American, a Finn, and an Englishman (p. 1).

Thanks to the presence of the scholars who joined LCHC during this period and to the timeliness of its academic and social preoccupations, LCHC continued to function as a “strange attractor” for scholars interested in our discussions about culture, development, technology, activity, and the ever-present reproduction of social inequalities. The people who participated in this work were in agreement that we needed a more adequate form of social science, even if they differed with respect to how they theorized the issues and the domains of social life upon which they concentrated.

Not only from other parts of the UCSD campus, but also from all over the world, many people began to visit LCHC. Through the efforts of various LCHC faculty, these visits were often used to crystallize discussions topics of common interest, organized as interdisciplinary conferences that gave rise to books that placed different, but allied, lines of scholarship into dialogue with each other. Two such enterprises illustrate the way that the Lab served as an incubator for participants’ later lines of thought and practice. One focused on the question of memory, and the other focused on work.

Memory

While a great deal of LCHC’s early work was focused on the role of culture in the development of memory, the study of memory continued long after cross-cultural research, or studies of memory development in children, were a focal concern.

Of particular influence in our thinking on this issue was the work in the after-school clubs at Rockefeller University, where we were impressed with the many ways in which overt remembering activities were more of a group process than an uninterrupted, individual performance.

It was only natural, given the people then at LCHC, that the topic of memory would be an important intellectual meeting ground. In April of 1986, the Lab conducted a workshop on “Collective Memory” that included a number of UCSD colleagues and several LCHC visitors. This workshop resulted, first, in a special issue of the LCHC Newsletter . The topic was later expanded into a book, Collective Remembering.

In the introduction, David Middleton and Derek Edwards (1988) specified the limitations of canonical modes of research on memory in the following succinct terms:

“…within that great variety of work [on memory], from psychoanalytic accounts of ‘repression’ to computer simulations of ‘memory processes’, the predominant focus of enquiry has been the study of memory as a property of individuals, or at the very best extending beyond individuals to include the influence of ‘context’ on what people remember. There exists a certain ‘repression’ for recognizing the social as a central topic of concern. When social ‘factors’ are considered, they are invariably treated as a social ‘context’ enriching the physical ‘background’ against which people exercise an individual ‘capacity’ to remember. To treat the social as only situational to, or at best facilitative of, a person’s memory is still to attempt what might be described as a ‘single-minded’ approach” (p. 1).

This characterization of prior theorization certainly fit much of our own cross-cultural and developmental research in the 1960s and 1970s. But, as noted, very similar concerns had surfaced in the research on ecological validity, where we saw clear examples of remembering as a social, collaborative, constructive process at work. A clear illustration of this process at work is given in Chapter 7 when children set out to remember how many rooms a child has in her (very spacious!) New York apartment.

All we had were clear instances of the phenomenon of memory as a socially distributed, culturally mediated process. We had encountered the problem of “going beyond social factors” close up, but we had not worked out the full implications of what we had witnessed. David’s introduction to the papers from the original conference characterized the changes that confronted those who sought to address the shortcomings of a “social factors” approach as follows:

“Acknowledging that information and knowledge can also be located in the world beyond the individual, be that a physical or social environment, certainly shifts the balance of the analysis away from a “single minded” and “egocentric” cognitivism but it begs the question of just what mediates the relationship between the two” (p. 2).

David then linked the issue of collective memory to the fundamental problematic of the lab, the relation between culture and cognitive development.

Consideration of the notion of collective memory and the activity of collective remembering provides a link between culture and mind in the following sense. The properties of a culture, embodied in its artifacts, tools, social customs and institutions, language and terms of reference provide a historical dimension to everyday living that enables knowledge of what has already happened or been achieved to be used in the service of present and future activity. Our modes of being and doing are cultural products that constitute a guiding constraint concerning what form our present and future actions should or could take.

The concerns expressed in the papers, and the methods that different scholars were bringing to the problem almost thirty years ago, remain central areas of concern at this text is being written.

Work

As one of the central forms of activity organizing adult life, work was a topic of interest from the very inception of LCHC. After all, our earliest studies of everyday adult activities became a key benchmark against which we evaluated questions concerning the role of mathematics in everyday life. But, work as a distinctive form of activity first became a central concern for LCHC owing to the Sylvia Scribner and her research group at the City University of New York (see also this special issue of the LCHC newsletter).

Throughout the 1980s, adult work settings were the focus of intense research of memory in “everyday settings,” many of which were specialized work settings: as a bartender, a waitress, a candy seller, as well as many more. The Quarterly Newsletter for these years is a rich source from which to get a sense of the broad interest in analyzing the cognitive constituents of various kinds of work as a way of studying “cognition in context.

These interests were brought together following Yrjo’s arrival in a “Work Research Conference” at LCHC in 1988, which focused on how workers within organizations interpret, represent, and share knowledge in conducting their work tasks.

We followed up from this conference through contact with a number of like-minded researchers, resulting in a book on Cognition and Communication at Work several years later. The range of authorial expertise and topics exploring these themes was enormous. For example, Lucy Suchman reported on the collaborative problem solving that takes place among airport workers. She analyzed the complex coordinating challenges that arise when the operations staff interacts with the ground crew and pilots of an aircraft that cannot be properly unloaded because the exit ramp at the gate has not been properly connect to the plane. She shows how individuals working in different parts of the airport, who are initially preoccupied with their own tasks, become mobilized into a coordinated unit in order to repair a breakdown. A similar result is reported in a case involving the London Underground. Chandra Mukerji, by contrast, highlights how workers at Scripps Oceanographic Institute work to pump up the reputation of their laboratory’s director as a means of creating a unique “laboratory signature” and increase the quality of the overall operation.

We followed up from this conference through contact with a number of like-minded researchers, resulting in a book on Cognition and Communication at Work several years later. The range of authorial expertise and topics exploring these themes was enormous. For example, Lucy Suchman reported on the collaborative problem solving that takes place among airport workers. She analyzed the complex coordinating challenges that arise when the operations staff interacts with the ground crew and pilots of an aircraft that cannot be properly unloaded because the exit ramp at the gate has not been properly connect to the plane. She shows how individuals working in different parts of the airport, who are initially preoccupied with their own tasks, become mobilized into a coordinated unit in order to repair a breakdown. A similar result is reported in a case involving the London Underground. Chandra Mukerji, by contrast, highlights how workers at Scripps Oceanographic Institute work to pump up the reputation of their laboratory’s director as a means of creating a unique “laboratory signature” and increase the quality of the overall operation.

Reviewers of Cognition and Communication at Work nicely summarized the overall contribution of the volume in the following terms (Porac & Glynn, 1999):

These are just two of many such conferences and subsequent publications that took place during this busy period in Lab history. For further examples, see the brief summaries in the 1992 Document.

Chapter Nine Compositors: Katherine Brown and Michael Cole

Back to Section Four

Forward to Chapter Ten