Details about the header picture

In this chapter, we focus on research that built directly on the lines of work we began while LCHC was at Rockefeller University, and then we turn to the new lines of research that became possible because of the Lab’s cross-country move from New York to California. First, we present two studies in the re-located LCHC that were devoted to the study of ethnic diversity. The first study focused on bilingual reading instruction and was conducted by Luis Moll, Esteban Díaz, and their colleagues. The second study, spearheaded by Alonzo Anderson and his colleagues, concentrated on the participation of preschoolers in literacy practices in Anglo- African- and Mexican-American working class households, neighborhoods and schools.

Next, we turn to studies that followed directly from the work on ecological validity at Rockefeller. The first we refer to as the “Oceanside School Project” (it was conducted in Oceanside, about 25 miles north of UCSD), in which we sought to embed “same tasks” in “different contexts.” This work was carried out in a school setting where the tasks were embedded in curriculum units designed and implemented collaboratively with two teachers in a mixed 3-4th grade classroom. The second follow-up study began as a way to further investigate the important set of issues posed by the child identified as learning disabled during the after school activities. This line of work ended up as a model system for re-mediating reading difficulties.

Two additional lines of work were intertwined with and informed these empirical studies. The first involved the infusion of microcomputers and computer networks into LCHC research and teaching practices. The second involved a new generation of collective theoretical work that grew up alongside the empirical projects.. However, because each these topics is so substantial, we have chosen to devote special chapters to each. We will make clear potential links for those who wish to “skip forward” as appropriate.

Reading in two languages: A teaching experiment

In 1978, the existence of an achievement gap among Hispanic students was no less an issue than it is now. We (Luis Moll and Esteban Diaz) undertook a study of bilingual instruction focused on the organization of elementary school reading instruction as a potential barrier facing Hispanic children (Moll & Diaz, 1983; Moll & Diaz 1987). The classrooms we studied were in a bilingual school south of downtown San Diego. The children were classified generally as limited English speakers.

This school featured a “dual instruction” reading arrangement whereby students spent half of their day in a Spanish-language classroom, and then rotated en masse to a separate English-language classroom for the remainder of the school day. The teacher in the Spanish-language instruction setting was fully bilingual. The teacher in the English-language classroom was a monolingual English speaker. This dual-language arrangement allowed us to study the children “doing reading” in two distinct language environments.

We videotaped the instructional interactions of the three reading groups, which were organized according to ability, in each of two third-grade classrooms. The videotapes documented the types of activities that were dominant in each lesson, and they provided a window into understanding ideas about what counted as reading in the different ability groups among teachers and children. We came to view these lessons through a Vygotskian lens, focusing on the way that language mediated the different kinds of practice associated with the designated ability groups.

In the Spanish-language classroom, the children were divided into three groups, ranked according to their assessed reading ability. The goals and practices that organized instruction differed markedly according to ability grouping.

- In the low reading group, instruction focused on a combination of decoding and simple, text-bound comprehension questions.

- In the middle group, there was more emphasis on comprehending the story by appealing to details in the text than was evident in the low reading group. The children were required to formulate their answers in complete sentences, while fragmentary answers were accepted in the low group.

- The high reading group presented the sharpest contrast in terms of the teacher’s expectations and the nature of the activities. The most obvious change was that the children were required to write book reports.

Here is how we wrote about the characteristics of this highest group:

“This activity typifies the most advanced reading related activity found in this classroom. The students have to select books of interest to them, and without teacher help, read them, analyze the contents, and write reports. Through the process of writing reports, the children practice reading and at the same time display their mastery of all the skills we observed in the three lesson environments. This activity culminates in the children’s carrying out independently there a ding behaviors with new materials and creating a new product (i.e., the book report) in the process (c.f. Wertsch, 1979). Again, the children are observed to successfully assume the mediations that are the responsibility of the teacher during the reading lesson we have described” (Moll, Estrada, Diaz, & Lopes, 1980, p. 56).

There were also marked qualitative changes in the ways the teacher interacted with high reading group students. In contrast with the two lower-level groups, the questions in the high reading group were more spontaneous and informal. They were also less text-bound, drawing upon related matters outside of the text itself. The teacher pursued questions that arose from the exchanges with the students and the topics developed by these exchanges. Furthermore, the emphasis was on communication of generalizations drawn from the reading.

What struck us when we made these observations was the way in which, within each reading group, the teacher stretched toward more and more developed forms of literate communication, putting the children’s practice in “the basics” within the context of comprehending the text as a whole.

These observations in the Spanish language reading class did not seem much different from many other well-run classroom-based reading lessons, either in organization or in intent. However, when we observed the same children during their reading instruction in the English-language classroom, we were in for a shock.

The English-language classroom was also divided into three ability groups. However, the level of reading that was focused on was at a much lower level for every group: instruction for all the children in the English-language classroom focused on providing the children with practice in producing correct word sounds.

Strikingly, even for the highest reading group in English, which consisted of the students the highest reading group in Spanish who were writing book reports and using the text as a basis for deeper comprehension discussions, the English teacher focused on the level of individual words, and comprehension never entered the instructional sequence. Here is an example:

- Student: Jill … Jill likes to hide she likes play. She likes play tricks … tricks when …. when …

- Teacher: Well!

- Student: “Well, then, said Henry. Where can we be hiding?

- Teacher: Monica?

- Student: Let me think, said Rose. Then she saw a …

- Teacher: She

- Student: She saw

- Teacher: Sheees…

- Other student: Said

- Student: She said …..

At times, the teacher would explicitly focus on word sounds, as in the following example:

- Teacher: All right, put your books down. All right, I’m gonna read you some words …I want you to tell me the beginning sound and we’ll do some, you do the end sound. “Glad.”

- Student: “guh”

- Teacher: “Eat.” (Looks at another student) “Eat.”

- Student: “eee”

- Teacher: OK, eee. “Fun” (looks at another student).

Even when issues of comprehension did arise, the teacher structured his questions in a way that reduced the students to providing one-word answers:

- T: “Sue played in the playground after lunch.” Where did she play?

- S: (The students bid to answer)

- T: Julio.

- J: Playground.

- T: All right, on the playground. Who was it? Who was doing this?

- S: Sue

- T: All right. When was it? When was it? Eduardo.

- S: After lunch.

- T: All right, after lunch. “Joan had dinner at night at their own house.” When did she have dinner?

- S: At night. (Lesson continues)

We found these results genuinely perplexing. What could it mean for children to be able to speak and comprehend spoken English, clearly the case for the students in the highest level reading group that read for comprehension in Spanish, but to be at the very beginnings of “learning how to read” (which their teacher interpreted as phonics drills) in English? The explanation for these differences, we argued, arose for three interconnected reasons (Moll & Diaz, 1987).

First, the English language teacher adhered to a “bottom-up” decoding-then-comprehension theory of instruction, so the lessons focused on decoding because the children still spoke accented English. They appeared, to the teacher, to be unable to decode correctly. There was, then, a confounding of pronunciation and decoding.

Second, because the teacher did not speak Spanish, she could not test her own interpretation of the children’s capabilities.

Third, there was no communication between teachers in the English and Spanish classrooms. The English teacher was present in the morning, while the Spanish teacher taught in the afternoon. As a result, the English-speaking teacher did not know that her pupils could read, and the Spanish-language teacher had no idea what was going on in the English classroom where, comprehension did not enter in any important way into reading instruction.

Developing the teaching experiment

At this point, our reading of Vygotsky provided us with a different interpretation of the entire situation. Our observations led us to suspect that the children could comprehend written English better than the teacher realized. To check out this idea, we initiated a teaching experiment by asking the fourth grade English-language teacher to teach a regular lesson with three girls, Sylvia, Delfina and Carla, whom she had assigned to the low reading group.

We knew from our observations of these same girls in the Spanish-language classroom, that they were all able to read Spanish with comprehension, although they varied in their reading group levels. We first present a brief segment of the students in the English-language classroom attempting to answer a question about a story they read regarding children visiting a fire station. The teacher asked them why the children thought that Isabel, one of the story’s characters, was lost in the fire station:

- Delfina: Because the boys and girls, um, looked… (Sylvia raises her hand)

- Teacher: Sylvia

- Sylvia: Uh, because the boys and girls, uh (pauses, laughs) the … um …

- Delfina: Had to go home

- Sylvia: Because the boys and girls go ….

- Teacher: Mhmm…

- Sylvia: … out in the first place and the girls not say “I am here.”

To us it seemed that, even to an experienced teacher, as was the case here, it would be reasonable to conclude that these children could not read and understand this text. But, based on our observations of the same children in the Spanish reading classroom, we doubted that they were failing to comprehend the text.

To test this assumption, a few minutes after the English language teacher completed her lesson, Esteban sat down with these same students and asked the same question in Spanish that the teachers had just asked in English. How did the others know that the girl was lost? Here, in translation, is Sylvia’s answer:

- Sylvia: Because he, she, they would shout for her and, and, they searched everywhere in the building where the firemen live and she wouldn’t answer.

- Later she elaborated: Because David said that they had to leave. Then they said “Who’s missing? No one’s missing, then they said “Isabel.” Then they started to search and they couldn’t find her and they said, “She’s lost, sir.” The fireman said, “No, no, she can’t be lost.” So they were looking for her and they got to the truck and the man said that there was Isabel.

It seems pretty obvious that Sylvia understood the story she had read in English, but that such understanding did not display itself in the regular English-language lessons. Instead, phonics instruction to improve pronunciation ruled.

Many examples convinced us that despite their oral language and decoding difficulties in English, all of these students could understand much more written material than the English language teacher could access, which impelled her to a bottom – up, fragmentary, individual word, focus. These conclusions led us to elaborate the teaching experiment with these same students to see if we could use their Spanish reading comprehension skills to advance their English reading lesson performance. Could we create a bilingual version of Vygotsky’s idea of the zone of proximal development for English reading?

Developing a bilingual zone

On the basis of these kinds of observations we sought to determine if we could create a zone of proximal development that would enable students to display the ability to read at their assigned grade level in English. We hypothesized that the children’s Spanish reading level would be a useful indicator of the top of their zone of proximal development for reading in English. This implies that English reading should be taught in the context of what the children could do in Spanish, especially their ability to comprehend in that language. The challenge was to provide support to hold such competencies in the interaction as we progressed with the lesson in English.

The major implication of this work was that strategic bilingual assistance can promote reading for comprehension in English among limited English speakers. This work has not been systematically followed up, but we suspect that when issues of pronunciation and individual word meaning are fronted in the way that the English-language teacher conducted her lesson, the transfer of reading skills from Spanish to English is actively interfered with: the children cannot display what they know and did not receive appropriate instruction.

Speaking from the perspective of the present, an unfortunate fact about the problems we set out to solve is that the organization of reading in classrooms with students now commonly referred to as English Language Learners features the same instructional issues we addressed during these study of bilingual students. This pattern signals the operation of an English-only ideology combined with a purely bottom-up, “correct phonic representation” curriculum that underestimates student abilities. We concluded that it is the identification and use of resources in the learning environment, in whatever language, that forms the bases for positive change in education.

Early literacy in family contexts: A comparative study

During approximately the same period of the Moll and Diaz studies, Alonzo Anderson assembled a diverse group of social scientists to study the early literacy development of preschool children living in low-income African-, Anglo- and Mexican-American households.

In an extension of the work conducted by Bill Hall, Anderson set out to examine the widespread belief that absence of books in the homes of poor and ethnically diverse children compounded their difficulties in school because they arrived with no experience of written language use. The number of books in the home was a standard component of various “cultural deprivation” indices (Totsika & Sylva, 2004, offer a review).

As in the case of oral language, far too much emphasis, from our perspective, had been placed on the home-based, cultural impediments to literacy, without any direct observations of when and how literacy came into the lives of poor families of different ethnicities. Correlations between number of books in the home and school performance were readily calculated but information about actual literacy practices in such homes, with the exception of homework and story reading, appeared absent from the literature.

At the time we began the study, there were few guidelines we could draw upon in conducting our observations of different families. We decided to focus on what we referred to as a literacy event, which we defined as “any occasion upon which a person produced, comprehended, or attempted to produce or comprehend written language” (Anderson et al, 1980, p. 59). We concretized this definition by characterizing such events as “any time the target child (TC) or anyone in the TC’s immediate environment picked up a book, wrote a note, signed his or her name, scribbled or was in any other way engaged with written language” (Anderson et al, 1980).

Members of the research team, who were of the same ethnicity as the population being observed, collected data on literacy events. Observers were present for relatively long periods of the day in order to be able to observe a variety of different kinds of activities in the home and local community during different parts of the day and week. Observers attempted to describe: the actions that took place; the conditions, materials and circumstances that gave rise to a particular literacy event; the participants in the event; any activities which co-occurred or alternated with the literacy event; the reasons why the event ended; and the activity that occurred subsequent to it. From such a holistic description we hoped to draw conclusions about the occasions that give rise to literacy events and to determine how these occasions varied across ethnic group.

We collected data over 18 months in 24 low-income households in three primary ways:

- Naturalistic observations, which were written up as field notes both during and immediately following a period of observation

- Self-reports

- Controlled behavior sampling – Each family in the study was the subject of four hours of observation per week, and the researchers rotated their observations through all phases of the day and all days of the week

The observations by the researchers, which ultimately yielded more than 1,400 literacy events, were supplemented by self-reports or diaries that the families kept about any literacy related event in their routines and by behavioral sampling related to the TC’s identification and understanding of literacy artifacts. Building on the work of Luria (1978 [1929]) and Ferreiro (1978), we also conducted interviews with the preschoolers to obtain their understanding of the graphic system and it uses. Here we will concentrate on providing an overview of the household observations of the literacy events.

The sheer number literacy events observed brought the researchers to another critical challenge: how to make sense of the volume of events recorded in field notes. The wide range of literacy events that were observed represented a real coding problem. Our field notes were not check sheets. There was no accepted taxonomy of home literacy events that involved 2-4 year olds, so we had to build a descriptive scheme and then, using this scheme as a starting point, code each event into its assignable category for the purpose of data aggregation. We organized literacy events into nine domains of literacy activity: Daily Living, Entertainment, School Related, Religion, General Information, Work, Literacy Techniques and Skills, Interpersonal Communication, and Storybook Time (for details, see the summary in the original text).

From the very beginning, our data indicated that the literate environment of these children was far from desolate. Literacy events of a great variety of types occurred during all of the observation sessions. Print gets incorporated into activity not as an isolated event but as elements of ongoing action that was itself embedded in an ongoing system of activity. As we conceived matters, the literacy events occurred within particular contexts (i.e., within particular socially assembled situations or activities). Through a careful analysis of the various literacy contexts as observed and described in the field notes, the researchers identified several elements of these complex literacy situations.

Here is how we explained this interweaving of literacy and action at the time (Anderson & Stokes, 1984):

“Once we began the detailed qualitative analysis of our field descriptions of the literacy events our team observed, we noticed that the type of literacy technology being used and the actions constructed around them were implicated in the events in non-trivial ways. First, the material could be linked to other organizations and institutions outside of the home. That is, the originating point of the material involved in most literacy events could be traced directly back to particular segments of the society, e.g., the trade economy, the school, the church, the welfare system etc. Second, particular material was associated with a particular sequence of actions. For example, TV or movie listings were used exclusively in an instrumental way to select entertainment, the Bible was used exclusively to learn or teach “the word of God,” a shopping list was used exclusively for shopping…” (p. 28).

In addition to categorizing literacy events into domains and tracing the sources of their origin in the families’ social worlds, we also found it useful to distinguish the dominant motives for reading. Drawing upon the work of Tom Stitch (1974) whose research focused on adults in the armed forces, we thought it useful to distinguish two kinds of literacy events that differ in their orientations in a manner directly relevant to the issue of home and school literacy events.

The first he called Literacy-To-Do (LTD), the purpose of which is to alter some aspect of the material and/or physical environment where the objective is “doing” something. In LTD, literacy is a means or a tool toward achieving a practical goal. The second form of literacy activity he called Literacy-To-Learn (LTL), where the objective is to produce, refine or manipulate some aspect of literacy practice itself. During LTL events, reading and/or writing are both the tool for teaching and learning and simultaneously the objective of the activity. Detailed field notes of this kind provided the raw data for comparative analyses across groups and kinds of literate activities.

It seemed clear from our findings that poor children, regardless of ethnicity, were arriving at school with considerable experience of the ways reading and writing are used in their local community and with at least the rudiments of how to engage in them. The greater frequency of LTL in the Anglo group almost certainly arose from the fact that (collectively) the Anglo parents, despite their assigned social class status, seem to be more focused on school-derived forms of literacy activity. However, in no way should this be interpreted as an exclusive focus of the Anglo families. Both African- and Mexican-American families also demonstrated a very real concern for school-derived forms of literacy activity. We also considered it important to note that when literacy events arose in the home, they almost invariably had their origins in some event that linked the home to the larger social world, whether it was the TV guide and entertainment or for religious purposes.

For members of LCHC, the results of this project reinforced our belief that poor children did not come to school as blank slates who were entirely ignorant of literate skills, just as they do not come to school a-lingual. However, these skills were more often associated with LTD tasks at home, which stood in stark contrast with the LTL orientation of the school.

This study suggested that there was fertile ground for early education specialists to cultivate their efforts to establish and develop LTL knowledge and skills. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that the knowledge of literate practice that their students developed outside of school (primarily of LTD) was ever used inside of school to promote the teaching/learning of LTL knowledge and skills.

The Oceanside Project: Making Same Tasks Happen in Different Settings

Our work with the after school clubs at Rockefeller had impressed upon us the importance of remembering that cognitive tasks do not “just happen.” They are made to happen in joint activity among people and in places called homes, workplaces and schools. Schools are distinctive with respect to other settings in in the multiple ways that they channel the process of “making cognitive tasks happen.” They are, normatively, places where children answer teacher questions and take tests. Under such conditions, the definition of a task is relatively straightforward because classroom interactions conform, more or less, to the constraints that characterize cognitive psychological experiments. But when some of the key constraints required for normal schooling are lifted – for example, the constraint that children solve problems on their own, or the constraint that culturally valued knowledge be obtainable only through print – the conditions that make cognitive tasks visible simultaneously erode.

The reasoning about how cognitive tasks become visible for analysis from a constructivist perspective suggested that we should not seek to discover “naturally occurring” cognitive tasks. Instead, a lot could be learned about the social organization of standard developmental tests if we deliberately sought to make the same task happen in different settings and then observed how it is reassembled, transformed, dispersed, or destroyed in the course of the activity of which it was a part.

We chose to work predominantly in regular public-school classrooms rather than the more free-form after-school club context specifically because the teachers maintained control over the activity structures and provided explicit topical connections between lessons and activities within curriculum units. These characteristics gave us a structure that allowed for variation in the kinds of activities students engaged in, while providing a way of repeating topics in different activities associated with the same unit.

From the outset, we worked collaboratively with the teachers to create curricular units that embodied cognitive tasks. The “we” in this case included Denis Newman and Peg Griffin who took day-to-day responsibility for the project. The teachers who made this work possible were Marilyn Quinsaat, Kim Whooley, and Will Nibblet. Bud Mehan, Margaret Riel, Sheila Broyles, and Andrea Pettito also made important contributions to various aspects of the project. During the course of two years, researchers and teachers developed and implemented experimental curriculum units in science (electricity, animals, household chemicals), mathematics (long division), and social studies (Native American Indians) (See, for example, The Construction Zone and read more at our Oceanside School Project Page).

Within each unit we arranged for “the same tasks” to occur in a variety of social circumstances: large group lessons, small-group activities, tutorials, and an after school club-like activity. We conceived of the common logical schema shared by implementations of the curriculum in different instructional contexts (small group, one on one tutorials, etc.) as “problem isomorphs” (Gick & Holyoak, 1980). But rather than studying the isomorphs with the laboratory setting, we attempted to make the isomorphs happen across a variety of settings.

The contents of each unit implemented a part of the state-mandated educational objectives for 3rd and 4th graders. For example, the household chemicals unit was chosen as a way to implement a science requirement. It was suggested by a teacher who was concerned about spontaneous fires from mixing cleaning solvents and other health hazards in the home. We were delighted with the idea because it seemed likely that the children would find mixing chemicals fun and would be motivated to see what happened when different chemicals were mixed. There was also a well-known Piagetian developmental task involving combinations of liquids. So, developing an activity that involved combining pairs of chemicals fit readily in the household chemicals unit.

A Standard Combination of Variables Task

We engaged the children in various tasks that required finding combinations of elements. The first was a one-on-one, adult-child task in which the children were presented with stacks of little cards. The cards in each stack contained a picture of a different movie or TV star. The children were asked to find all possible combinations of the people pictured on the cards. The children were given no indication that the cognitive task in this activity was to be associated with the household chemicals unit; and certainly not that the researchers saw it as a problem isomorph of what the children would encounter later as part of the household chemicals unit.

Starting with four stacks, each child was asked to find all the ways that pairs of movie stars could be combined (e.g., to find all possible pairs of cards). When the child had completed as many pairs as possible, the adult instituted a bit of training by asking the child to check to see if any pairs were missing, and modeled a systematic checking procedure (“Do you have all the pairs with Mork?” Do you have all the pairs with Elvis?” etc.). When the checking was completed, the stack of cards was put back together and a fifth stack was added. Again. the child was first asked to make all the possible pairings and then coached in the checking procedure if such coaching was needed. When the child completed the task with 5 stacks of cards, a 6th stack was added and the procedure repeated.

We scored performances for any instance of a child going through part or all of the pairings involving a particular card, such as 1&2, 1&3, 1&4. As would be expected for children this age, few children used a systematic logical procedure without help, although a majority began to display systematic strategies for pairing cards after they had been through the checking procedure.

A Version of the Combination of Variables Task

Later, as part of the household chemicals unit, these same children also participated in a small group activity where three or four children went to a work area at the back of the room where they were asked to find combinations of chemicals in beakers. Each group was given four beakers containing colorless solutions numbered to make them easily identifiable. They were also given a rack of tubes, a sheet of paper with two columns marked “Chemicals” and “What happened?” on which they were urged to record their procedure and results. The chemicals were chosen so that each combination would produce a distinctive coloration of the liquids. After the teacher asked one of the children to read the instructions aloud, she told the group to investigate all the possible pairs and busied herself with paperwork to make it clear that the children should proceed on their own.

Because the children who completed the movie star tutorial also completed the chemical combinations task, we could compare their performances across settings to see if they responded in the same way to the tasks in the two settings. But here the different social contexts of the tasks made themselves clearly felt. In the two person tutorial, the procedures divided the cognitive labor relatively neatly between the child and adult so that for each move in the problem it was possible to say either that the child did it on her own or she was helped in varying degrees by the experimenter. But in the multi-child chemical pouring task, matters were considerably more complicated.

Since there was no imposed division of labor for the mixing of the liquids, it was often impossible to determine how much each child contributed to, or understood about, the solution of the combination task. For example, if one child was in charge of pouring and one child was in charge of recording, their interactions may not have revealed the understandings of the recorder. This difficulty follows directly from the additional freedoms allowed to the children by the teacher, and it confirms the difficulty of drawing conclusions about “same task in different settings” even when we make certain that the same task is there at the outset of the interaction. The normative constraints of the activity overwhelm the constraints of the task.

However, we also discovered that embedding the pairwise combinations task in a multi-person activity revealed an important aspect of the task that the standard procedure routinely obscured — the children’s own discovery of the goal of the task as formulated by the adults. When finding all combinations of chemicals, the children started out by addressing a problem that does not arise in the standard version of the task– how to make sure that everyone gets a fair turn to test the reactions caused by different combinations of chemicals. Only after a turn-taking procedure and division of labor was worked out did the children turn their attention to the question of which chemicals to combine. Initially there is no evidence that the children were in fact oriented to the task of discovering all possible combinations of chemicals. Disputes were more likely to concern fair turn taking than the question of which chemical combinations had been attempted and with what outcomes.

Once the children solved the problem of social equity and succeeded in testing several of the possible combinations, the task we were interested in (finding all possible combinations) arose because of the need to know if there were any more turns to be taken. In these circumstances, the children spontaneously articulated their involvement in the task of finding all possible combinations because they needed to communicate with their partners about the ongoing social order. By contrast, in the one-on-one tutorial sessions using combinations of cards, where we had excellent evidence about what parts of the adult-defined task the child fulfilled, we never obtained evidence that the child actually formed the goal intended by the adult. Children conformed to already-formulated (by the adult) goals by making pairs, but because it was (implicitly) the adult who was responsible for seeing the child reached the goal, the goal-formation part of the problem-solving task did not arise as a social issue. As a consequence, when children performed poorly, it was difficult to know if they were failing to do “the” task (e.g., that they shared the researcher’s specification of the goal) or if they were pursuing some alternative formulation of what the task might be.

An additional event in this combination of variables research is worth mentioning because it affirms again the fragility of “same tasks” even when they make an appearance in a particular setting. Bud Mehan and Margaret Riel conducted an out-of-school version of the combination task, which we called “The Back Pack Bears.” On the occasion in question, the children were engaged in the task of choosing meals for a hypothetical hike of several days duration. Each meal was to be a stew made up of two ingredients out of a possible 5 ingredients (carrots, beans, peas, etc.). The children start out to make different stews with different ingredients, and for an instant, the task of finding all combinations emerged. But it lasted no more than a few steps because the children picked the ingredients they liked best and ignored the rest of the task. This result came as no surprise given our experience in the cooking club at Rockefeller, but it did serve as a reminder that the presence of “the task” in an activity must be jointly achieved and maintained.

Another part of the household chemicals unit provided an important lesson about the conditions under which teachers make assessments of children’s knowledge as part of classroom lessons. The lesson in question was designed to prepare the children for the chemical mixing task just described. In this lesson, which was given to four to six children at a time, the teachers intended to provide the children with hands-on experience mixing chemicals and record keeping. Initially the teachers expected the lesson to have a “wrap up” phase in which they would discuss the range of reactions the kids had created by the different combinations. They also knew they were preparing the kids for the full-blown experiment in mixing chemicals, where the sub skills of mixing and recording would be necessary.

As a consequence of all these plans and the procedures for implementing them as part of meaningful problem solving tasks, when the lesson began, the goals of the teacher and the children were very different. The teachers were attempting to prepare the children for upcoming tasks. The children, of course, knew nothing of this future. They were simply excited to get their hands on real chemicals after hours of talking about them.

The lesson was structured so that the children first mixed each of the two assigned chemicals and then wrote down what happened on the record sheet. They did this twice, for two different pairs of chemicals. The teacher oversaw and coached the work of each group as she deemed necessary.

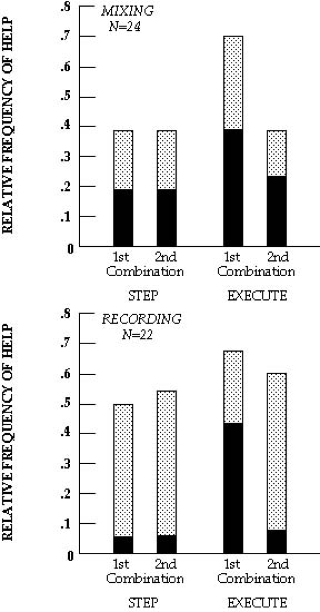

Instances of teachers helping children were coded in terms of two sub-tasks: mixing the contents of the two beakers, then recording the results on the record sheet. Within each sub-task, we distinguished between low level help that focused on the mechanics of the operation needed (“step”) and a higher form of help (“execute”) that occurred when the teacher provided an overall explanation of how to complete the task. For each sub-task we scored the help children received into two categories: “Needed Help” and “Cannot Tell if Needed Help” because in many cases, the teachers gave help when the child had not asked for it, but in circumstances where it might have been needed. For example, teachers would give help in response to a request about mixing the content of two beakers and then tell the children to record it before we could assess if the children actually needed a reminder to record or not. Results are shown in the figure below. For the black section of each bar in the graph, the child visibly needed help; but for the stippled section, there was no indication that the child sought help before the teacher provided it.

Several aspects of the results in the figure are worth highlighting. First, note that a large proportion of the help in almost all cases is ambiguous in the sense that the child gives no discernible sign of a need for help. Second, the amount of help in executing the desired action decreased from the first to the second problem, indicating that children were learning the task. Third, the amount of help the teacher offered often remained high even when the children did not ask for it.

To get a better sense of what was happening in the ambiguous cases, we interviewed the teacher. With respect to the overall high level of help she gave, the teacher said that this lesson was designed to prepare the students for the next lesson. She was particularly worried about the recording step because she had told the children less about it in her introductory instructions and because she knew that recording was going to be essential in the next lesson. With respect to the situations where she gave help that was not asked for, she said that she was just reinforcing actions she assumed the children could carry out anyway to make sure they would do the right thing in the next lesson.

Here we see the principle of prolepsis (the representation of a thing as existing before it actually does so): The teacher’s actions (and hence the children’s experiences) are guided not by contingencies of the moment, but by the anticipated requirements for action in the future.

Our work on this project was very much part of our coming to terms with Vygotsky. The title of the book that came out of the project, The Construction Zone, was meant as a play on zone of proximal development. Each chapter can be seen as part of our exploration of the developmental approach we were coming to internalize through the continuous dialog in within the Lab and with the many visitors during the period when this work was being done. The “zone” gave us a lens through which to understand what we were seeing in the classroom. We could see the children learning to use cognitive tools such as the systematic routine of checking and recording to determine whether all the pairs were found. We also came to understand that what is sometimes called “scaffolding” in the zone actually leaves open the possibility of children constructing new knowledge or tools, not just building the pre-conceived ideas of the adults.

Re-Mediation Reading Difficulties

Our work in the after school clubs described in Chapter 3 left us impressed with how much Archie had been capable of learning despite the difficulty he experienced in reading. Inspired by his abilities as much as his problems, we proposed a full-blown project focused on children labeled learning disabled, using a version of our “same task, different setting” strategy. In place of a single child labeled learning disabled we decided to study a classroom of children labeled in this manner and to treat the children as a set of unique cases to be studied in depth over the period of at least a year.

We planned to observe each child in their regular classroom, during special education training by the school’s learning disability specialist, on the playground during recess, in the neighborhood after school, and at home. Each child would also be given a battery of standard tests consisting of tasks widely used to make judgments about learning disabilities and undergo extensive cognitive skills training. Those were the plans.

The research got off to an encouraging start. We found two schools with demographically diverse populations of children, active programs for children who were identified by the school as poor readers, and a sympathetic remedial learning specialist. We planned to use one school as the locus of the cognitive training interventions and the other for comparison purposes.

Beginning with the first school, we made baseline observations of the children in the various settings and administered a standardized test for purposes of identifying the range of prouploads that the children presented. We discovered that if we judged by the test scores, the children were a diverse group indeed, including a few who fit classic prouploads of learning disabled children and many who did not.

However, at this point, the teachers began to express discomfort at our presence in their classrooms. We were turning out to be a nuisance, tolerated but not welcomed by busy teachers who could see no immediate payoff for their work in what we were doing. Despite support from the resource room teacher and the principal, teachers wanted to restrict our access to the children in ways that would have rendered the research useless from our perspective. Since we had begun standardized testing at the second school, we decided to move the focus of our work there. Much to our dismay, the teachers there also wanted to restrict our access to children during classroom lessons.

We had a great deal of sympathy for the teachers’ reluctance. They were under heavy pressure to raise the reading scores of their children – now. A new curriculum mandated by the school district specified precise amounts of time they should be spending on each topic at each part of the day. Perhaps they might have been more sympathetic to our presence if we could assure them that our research would improve the educational performance of the poor readers they were teaching more than their own efforts, but of course, we were in no position to offer such a guarantee.

Faced with this crisis, Peg Griffin and Bud Mehan met with the teachers and the principal as a group to see what could be done. The teachers agreed, reluctantly, to our presence in their classrooms. But they imposed further restrictions that would have thoroughly undermined the purposes of the research.

At this point, the project almost folded. Unwilling to give up and unwilling to go on under the constraints that were being imposed on us, we proposed moving the entire operation from the school day to after school in order to continue working with the children, but to take the pressure off the teachers. In place of observation of their educational activities during the school day, we would create our own lessons with our own curriculum content and then contrast behavior in those settings with the others we outlined in our original proposal.

The principal allowed us to use the school library located in a trailer on the playground. We invited all of the children who had previously been identified for our original study to participate. The after school program opened to 24 children ranging from 2nd to 5th graders, half of whom fit the clinical definition of learning disabled, all of whom were seen as problematic by their teachers.

The early history of this effort is summarized in a report completed the summer after we began to take responsibility for teaching children to read as a fundamental aspect of our research (LCHC, 1982). In brief, led by Peg Griffin, we created four different reading curriculum modules, each that drew upon extant research on reading acquisition. The four models were based upon the following ideas:

- Increasing comprehension through increasing lexical access based on the work of Isabel Beck and her colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh (Beck, Perfetti, and McKeown, 1982)

- Enhancing comprehension as internalized problem solving (from the Kamehameha Early Education Project, KEEP, 1981)

- Comprehension enhancement through the guided anticipation of meaning (Fillmore and Kay, 1981)

- Reciprocal reading instruction (Brown and Palincsar, 1982)

The children were divided into two groups of 12. They came on Monday and Wednesday or Tuesday and Thursday. Each reading module was implemented with half the attending children, while the others engaged in computer-based activities that we will describe in Section Four.

The approach to reading instruction embodied in each of these modules was distinctive in its simultaneous emphasis on three, inter‑related points:

- Reading instruction should emphasize both decoding and comprehension in a single, integrated activity. That is, reading requires the coordination of “bottom up” (feature ‑‑> letter‑‑> word‑‑‑> phrase‑‑> …) and “top down” (knowledge‑based, comprehension‑driven) processes out of which new schemas emerge (McClelland and Rumelhart, 1981).

- To achieve the right mixture of top-down and bottom-up sources of learning, reading instruction/acquisition is best conceived of as a joint activity in which there are participants with different entering skills, but everyone is engaged in trying to figure out what the text is all about.

- The success of adult efforts to diagnose and overcome instructional difficulties depends crucially on their organizing a “cultural medium for reading” which orchestrates the social relations required to re-mediate (mediate in a different way) the child’s system of making sense of the text (reading for meaning) in an effective way.

An Example Reading Activity: Question Asking Reading

One of the reading activities that was a part of the , Question Asking Reading (QAR), was designed to work at the level of small groups to produce the property of instruction that Courtney Cazden (1981) attributed to zones of proximal development – enabling “performance before competence.” Children were not required to do the “whole act of reading” in order to participate in QAR. Rather, they were asked to fulfill partial roles in a scripted, coordinated activity that would allow them to participate in the whole act of reading-as-comprehending. We expected that, initially, the adults and the artifacts used to play out the script would bear a large part of the load, but children would come to be fuller participants (e.g. more competent readers) over time.

The core of the procedure was a kind of parlor game implemented as a set of roles/division of labor, each element of which is relevant to figuring out what the text is all about. Each role corresponds to a different hypothetical part of the whole act of reading. The roles were printed on 3″x 5″ index cards. Every participant was responsible for fulfilling at least one role in the full activity of QAR. These cards specify the following roles:

- The person who asks about words that are hard to say.

- The person who asks about words that are hard to understand.

- The person who asks a question about the main idea of the passage

- The person who picks the person to answer questions asked by others.

- The person who asks about what is going to happen next.

All participants including the instructor had a copy of the text to read, paper and pencil to jot down words, phrases or notes (in order to answer questions implicit in the roles), and their 3×5 card to remind them of their role. The steps in the scripted procedure were written on the blackboard where answers were recorded. All these artifacts represent tools to be used by the adults to create a structured medium for the development of reading and by the children to support their participation, even before they know how to read.

In order to move from the script and other artifacts to an appropriate activity, the procedural script was embedded in a complex, ritual set of procedures designed to make salient both the short term and long term goals of reading and to provide a means for all the participants to coordinate around the script. Recognizing the need to create a medium rich in goals that could be resources for organizing the transition from reading as a guided activity to independent reading, the researchers saturated the environment with talk and activities about growing‑up and the role of reading in a grown‑up’s life. This entire activity was conducted after school in a global activity structure we called “Field Growing Up College” (it took place in the auditorium of the Field Elementary School).

Each session of QAR began with a discussion about the various reasons that children might have for wanting to learn to read. These included: poorly understood reasons (from the children’s point of view) such as the need to read in order to obtain an attractive job such as becoming an astronaut, intermediate‑level goals (such as graduating from QAR to assist adults with computer‑based instruction), and quite proximate goals (getting correct answer on the quiz that came at the end of each reading session).

Although we gathered data from the beginning of the first session, the crucial data for our analysis came after several sessions, when the children had mastered the overall script and the group was working as a coordinated structure of interaction.

Our strategy was greatly influence by Alexander Luria’s monograph, The Nature of Human Conflicts (1932), devoted largely to an experimental procedure designed to reveal “hidden psychological processes” (e.g. thoughts and feelings). The basic idea of Luria’s procedure, which he called “the combined motor method,” was to create a scripted situation where a subject had to simultaneously carry out a motor response (squeeze a bulb) and a verbal response (give the first word that comes to mind) when presented a stimulus word. In the most dramatic form of this procedure, which has subsequently been incorporated in lie-detector systems, Luria interrogated suspected criminals.

He began by presenting either simple tones or neutral words until the subject could respond rapidly and smoothly. Then, among the neutral words he was present a word that had special significance in the crime (handkerchief, for example, if a handkerchief was used to gag a victim). He argued that selective disruption of the smoothly coordinated baseline system of behavior revealed the subject’s special state of knowledge.

In place of a bulb to squeeze and deliberate deception, our concern was with texts, role cards, and the selective disruption of the smoothly running script of QAR. Hence, it was of paramount importance that we create the conditions for a smoothly coordinated joint activity mediated by the roles, special artifacts, and text.

The first few sessions, while the children are learning to perform the scripted activity, were anything but smooth. Eventually, however, the children got the hang of how to participate in QAR even if they had severe difficulties reading. The procedure became so routine that one could turn off the sound of the video recording and watch the synchronized movements of the participants around the scripted activity with occasional disruptions of coordination.

This background of coordination, and our ability to identify which child’s behavior was disrupted according to which role they were playing, provide the conditions for diagnosing individual children’s “hidden psychological processes” that interfered with their reading.

An instructive contrast was between two boys. The first child had little trouble dealing with the role of decoding individual words, but a great deal of difficulty when it came to answering questions about the word’s meaning or in putting together phrases to answer questions about the meaning of the passage. The second boy was also able to decode words, and he was quite verbal when engaging in discussion of the meaning of the passage. His problem was that he regularly lost track of the relevant information for answering questions about the passage. As a consequence, his contributions to the discussion were often incorrect as he put together the meaning of one passage with a passage that had preceded it, creating hash of the overall meaning of the story being read. The different points at which these boys became discoordinated marked these difficulties. This selective discoordination allowed us to make the relevant differential diagnosis that we were seeking.

A follow-up study comparing QAR with other leading instructional regimes of that time showed that it was a more effective intervention for children struggling to learn to read for meaning (King, 1986). In much later years, it was adopted in college classrooms as a way to engage college students in the kind of high-level literacy expected but not always encountered at the college level, where students schooled in answering multiple choice questions struggled to make meaning of their texts.

Summary Comments

Each of the projects summarized thus far opened up a new line of research that built upon the research program begun at LCHC while it was Rockefeller University. These continuing efforts took place in a number of different institutional venues, as young researchers, who either migrated from New York or joined the Lab at UCSD, went on to take academic positions at other institutions. For purposes of this narrative about LCHC at UCSD, we will next take up the multiple ways that computers and computer networks provided the object as well as the media of LCHC research as part of the transition to UCSD.

Chapter Six Compositors: Alonzo Anderson, Michael Cole, Esteban Diaz, Luis Moll

Chapter Six References and Additional Resources

Back to Section Three Introduction

Forward to Chapter Seven