A recurring theme of the work described in the previous chapters was our disenchantment with the use of standardized psychological tasks to draw meaningful conclusions about cultural variations in cognitive abilities. Whether dealing with cultural differences in remembering and logical problem solving or trying to design an experiment that adequately models Vai writing activities, we had come to agree fully with the epigram at the head of this chapter.

The challenge was to work out the implications of an alternative and more adequate way of understanding psychological tasks as a particular form of activity. This included being able to “locate” the experimental events with respect to their socio-cultural context. However, we were well aware that such a commitment in no way solved the problem of how to carry out such analyses in a manner that made methodological contact with the procedures of cognitive psychology on the one hand and cognitive anthropology on the other.

The approach that we adopted, like our earlier work in Liberia and the Yucatan, began from two distinct disciplinary poles: experimental psychology and ethnographic/social anthropology. On the one hand, we worked “outward” from the experiment as the embodiment of what cognitive psychologists define as a psychological task: a goal and the constraints on achieving it. On the other hand, we worked “inward” from the socio-cultural context to understand the interactional dynamics of the test situation, its constraints, and its prescribed goals so that a psychological task could be said to be happening.

By combining insights from these two converging modes of analysis, we hoped to open up an examination of the ways in which standardized tests also function as social events. In particular, we were keen to better understand their relation to the other events in people’s lives.

By combining insights from these two converging modes of analysis, we hoped to open up an examination of the ways in which standardized tests also function as social events. In particular, we were keen to better understand their relation to the other events in people’s lives.

In their 1974 book, Culture and Thought: A Psychological Introduction, Cole and Scribner lchcautobio a Kpelle proverb in their reflection of this dual orientation: “I know how to begin the old mat pattern, but I do not know how to begin the new.” They might, perhaps, just have written, “Easier said than done.” Criticism is the easy part. Arriving at deeper understanding of psychological tasks in relation to both the individuals engaged in them and their social contexts is far more difficult.

Ecological Validity

Addressing the need for a deeper understanding of the ways in which psychological tests are social achievements, LCHC was fortunate to attract a number of scholars who specialized in the study of social interaction. Conversational analyst Emmanuel Schegloff, ethnographer Ray McDermott, microsociologist David Roth, and developmental psycholinguist Lois Holzman each joined this group in 1976. In addition, we began active exchanges with Courtney Cazden and Bud Mehan, who visited the Lab regularly for seminars and shorter visits and were conducting an interactional study in a classroom with Cazden as the teacher. This network, which grew to include colleagues at Georgetown University and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, was an important resource for us as we began to develop a new and more coherent, if not perfect, methodology.

The interdisciplinary and interinstitutional interactions that defined LCHC began to focus on an issue in psychology that had disquieted the discipline’s development since its founding as an empirical science in the late 19th century: the problem of ecological validity. Ecological validity refers to the extent to which the psychological processes observed and recorded in a particular psychological experiment reflect the processes that actually occur in other, naturally occurring settings. Ecological validity is also used to address the problem of generalizability, which is the extent to which it is legitimate to apply the lessons learned in an experimental setting to the “real world” of events not deliberately set up for purposes of psychological testing.

The Manhattan Country School (MCS) Project

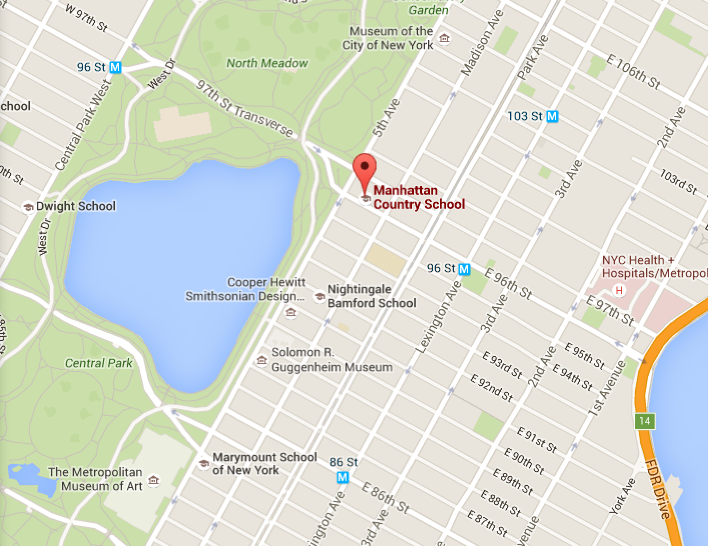

We referred to this research as the MCS Project because our partner in the work was the “Manhattan Country School,” located at 96th Street and Madison Avenue on the border between black/white, impoverished/affluent populations in the city. The school was deliberately highly diverse, with children representing a broad spectrum of social class and ethnic backgrounds.

We referred to this research as the MCS Project because our partner in the work was the “Manhattan Country School,” located at 96th Street and Madison Avenue on the border between black/white, impoverished/affluent populations in the city. The school was deliberately highly diverse, with children representing a broad spectrum of social class and ethnic backgrounds.

The core project participants (Mike Cole, Lois Holzman, Ray McDermott, and Ken Traupmann) decided to undertake a direct analysis of the relationship between cognitive psychological tasks, classroom lessons, and more informal, less restricted forms of activity where cognitive processes might be studied “in action.”

MCS research design and details

Begun in the fall of 1976, this research involved 17 children who were between 8 and 10 years of age and from a variety of ethnic and social class backgrounds. Roughly half were boys and half were girls.

The research team aimed to answer an essential question about cognitive consequences of schooling: Can cognitive difference be seen to operate in everyday settings that are not controlled by a researcher or a teacher? More generally, the team hoped to achieve a much better understanding of all of the social constraints that come together when children are taking formal cognitive tests, participating in classroom activities, and engaging in other forms of group activities.

We based our approach on the idea that if psychological tasks actually measure the sorts of things that also take place outside of experiment interactions, then we should be able to see people engaging in such tasks across a variety of settings. Specifically, we wanted to conduct this research in a way that would enable us to record the interactional dynamics that converged. This approach, we hoped, would enable recognizable psychological tasks to occur in each of three kinds of social settings: psychological tests, schoolroom lessons, and after-school enrichment activities.

On the one hand, the configuration of standardized test interactions served as the starting point of analysis in a search for “everyday life” settings that produced similar forms of events. On the other hand, we began with the configuration of the social interactions in the less constrained settings and sought to determine how they mapped onto the formal testing situation.

The series of tests we selected were meant to be representative of tests used to evaluate scholastic aptitude or cognitive development. For example, a free recall task has the goal of committing to memory as many items as one is able — with the constraint that the testing subject cannot not write anything down or “cheat” in any way. Said in another way, the aim is to achieve the goal, but not break the constraints. This kind of test highlights a subject’s ability to carry out the psychological task without overtly interacting with the environment, except in the manner closely prescribed and scripted according to the research design.

The tasks were administered by a professional tester who did not know the purpose of the study. Our battery included:

- The similarities subtest of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, which was modified so that a third item was added to the original pair in cases in which the child experienced difficulty.

- A mediated memory test first developed by A. N. Leontiev (1932) and Luria (1928) that allowed children to use one set of pictures to help them recall another set.

- A figure-matching task of the sort used to assess impulsiveness.

- A syllogistic reasoning task.

- A classification task involving common cooking and eating utensils.

We reasoned that because psychological tests model school practices, we should be able to “see” psychological processes at work in the testing and classroom contexts. Once identified, we thought we could then determine if the child performed equally well in both settings. However, we wondered what would happen if the social situation became even less constrained, yet saturated with potential cognitive tasks. To address this question we engaged the children in weekly activities such as a “Nature Club” and a “Cooking Club” that we hoped would reduce the frequency of school-like, and thus test-like, tasks. It was an open question: Would tasks occurring in the clubs or the test situation arise in the clubs, and if so, could analyze them usefully?

Visualizing the “socialness” of cognitive activity

Repeated observations over several iterations of the clubs revealed that the conceptual apparatus of cognitive psychology could, when there was the right combination of circumstances, provide a plausible explanation of differences between behavior in laboratory and what we called “everyday life” settings (represented in our case by the clubs). Sometimes these tasks arose spontaneously. Other times we tweaked the social organization of the activities at the club as a way of making the cognitive work being done by members of the group more visible and public.

The following is an example in which an arithmetic/memory task arose in an unpremeditated manner as the children were gossiping during a lull in the activities. They began to discuss how many rooms they had in their apartments. Dolores initiated the task of remembering by asking Jackie how many rooms she had and then asserting that she thought that the correct number was 13.

Jackie: Uhhuh, I just made, I, we just made a bathroom.

Mike: They cut one (room).

Dolores: (to Jackie) Count them all (Dolores holds up pinky).

Jackie: Three bathrooms (holds up three fingers)

Dolores: That’s not a room.

Reggie: They’re rooms. Bath rooms.

Jackie: No, I’m counting bathrooms. For my (holds our arms) whole house we got thirteen rooms. There are two (inaudible).

Dolores: (holds up 3 fingers) Three, two (adds 2

more fingers).

Jackie: Five (holds up 5 fingers also; Dolores adds

one more). O.K. (Jackie holds up six too).

Dolores: No five (holds up five).

Jackie: O.K. (holds up 5 too). My’ um’ mother’s and father’s room. Six (both hold up six). Then we have (Pause) um.

Dolores: Your room.

Jackie: My room and my brother’s room (both hold up

eight) and then we have um.

Dolores: The living room (9 fingers).

Jackie: The living room (9 fingers).

Dolores: The kitchen (10 fingers).

Jackie: The kitchen (10 fingers). And the place where we eat. The place where we eat. 11. And then we have, then when you walk (moves hands indicating direction) (inaudible) and you walk here. You know (pause) well we made a new room.

Dolores: Oh, well you counted that already.

Jackie: No, I didn’t count the new room.

Dolores: Yes, you did.

Reggie: Yes, you did count the living room.

Dolores: No, the new room. You counted the new room. (Discussion continues)”

Here both deliberate remembering and arithmetic reasoning were called for, and the problem was solved. However, the process was not clearly attributable to any one of the participants, many of whom contributed in ways that were relevant to completing the task before the group. The task had been distributed throughout the group in a visible sense. For example, Dolores stored part of the information for Jackie (with her fingers), actively joined in the recall process, supplied necessary information (line 13, line 1), and contributed by acting as a mnemonic cue for Jackie (line 15).

The distributed nature of this task (and many others like it that we identified in our videotapes) made visible the “socialness” of cognitive activity. The individual person (and her/his head) was not solving the task “solo”. We came away from such observations convinced that it is not valid to take the individual as the unit of analysis of cognitive activity. We were observing children and adults continuously arranging their environments so that they did not need to engage in cognitive activity without environmental support. “Non-internalized thinking,” in which cognition resides in the environment as much as in the individual, was more common than we might have thought.

Complexity in social environments

We began to move in a direction we hoped would be a more ecologically valid psychology, with the unit of analysis being the person-environment interface. Environment, in this context, encompassed the cultural and social surround, including, of course, other people and an array of artifacts. We were able to collect a number of similar examples from our many hours of recording. Although a great deal of time was put toward this effort, it was ordinarily difficult or impossible to say that particular children were confronting “a task” or to specify how they dealt with it. So long as one observed the behaviors of the children through the lens of cognitive psychological task analyses, the club behaviors seemed to reflect a standing rule of social interaction — to get past difficulties by changing the overall division of labor in the group to minimize the effort of the task.

From this perspective, cognitive tasks encountered in everyday life appear to be “easier” because they can be strategically re-assembled and minimized. At the same time, when one closely observed the videotapes, it became clear that in the less formal, more variegated environment of the after school club, the social environment was not always coordinated and supportive. Children virtually never entered any of the activities with only one task on their minds. We had learned that lesson on the very first day. What we were unprepared for, however, was the constant complexity of the intertwined social relations among the children and the ways in which they entered into the joint club activities with their identities constantly on the line.

From this perspective, cognitive tasks encountered in everyday life appear to be “easier” because they can be strategically re-assembled and minimized. At the same time, when one closely observed the videotapes, it became clear that in the less formal, more variegated environment of the after school club, the social environment was not always coordinated and supportive. Children virtually never entered any of the activities with only one task on their minds. We had learned that lesson on the very first day. What we were unprepared for, however, was the constant complexity of the intertwined social relations among the children and the ways in which they entered into the joint club activities with their identities constantly on the line.

Archie and Reggie

As we were in the process of coming to grips with the ways in which the organization of club activities changed the “cognitive division of labor” involved in solving a task, an unexpected event occurred. This event sharpened our focus on the intricate interplay between children’s abilities, including their academic abilities and the ways in which they deploy them to pass as full members of a social group. This particular case concerned a child who had been diagnosed as learning disabled.

Some relevant background information: In order to avoid “contaminating” his ideas about the children, Mike had avoided participating in the observations at the school. He was one of the “club guys.” After a few club sessions had taken place, it seemed an opportune time to visit the school and compare notes with the classroom teacher whose lessons were being observed and recorded. As they began to chat, the teacher asked Mike if Archie was proving to be a problem in the clubs. Mike was surprised at that idea. Thus far, Archie had seemed eager to participate in the activities. He was generally as helpful and engaged as the other children. By contrast, one of Archie’s companions, Reggie, was a big problem for Mike because Reggie kept getting into interpersonal difficulties that tended to spill into the hallways and disturb our colleagues.

“Didn’t you know?” she asked in surprise. “Archie is learning disabled.” The teacher’s news was a shock to the entire research group. We had been through several sessions of the club by this time. We had also observed in the classroom, but nothing in either setting had alerted us to this possibility. How could Archie be learning disabled at school and yet a perfectly normal participant in the club where reading and other forms of learning were pervasive?

Primed by the notion that Archie had difficulty with text processing at school, we began to focus carefully on moments in the flow of activity when Archie had to deal with print or some specific language issue. When we went back to check our videotapes, we found that Archie had indeed experienced some distinctive difficulties in the formal testing procedure, especially on language-related tasks, which are implicated in the notion of a “reading disability.” We also noticed from video recordings in class that he was a master at avoiding being called on to answer a question while seeming to be an ardent participant.

Our focused interest on moments when Archie was encountering print during the club periods coincided with a realization that we needed to pay far more attention to our own tendencies to fill in and help out the children when they encountered difficulties. Everyone, researchers included, shared the common goal of getting the task completed before the bus came to take children home (in this case, baking a cake). We wanted the kids to have a good slice of cake just as much as they did, and we were acutely aware of the time constraints.

We decided to ease back on our own “filling in” actions to the extent that it was possible. The children would have to do more of the work. In the process of stressing the children’s abilities, we hoped that we would be able to create a “slow motion” version of their cognitive processes at work.

This strategy worked particularly well. Some of the most interesting observations from our subsequent work came from two occasions when Archie worked with Reggie. There was some tension in the relationship between the two boys because, in prior weeks, Archie had shunned Reggie in order to work with Tony, another child in the class. On the day in question, two deviations from the normal routine coincided. By prior arrangement, Ken Trauppman told the children that Mike was not available and that he would be busy with some paperwork over in the corner. He had already gone over the routine with them. This time they were on their own.

On this occasion, Tony was absent, so by default, Archie and Reggie baked cranberry bread together (the girls had already gone ahead to organize their own activities). Keep in mind that while Archie was a poor reader, he was a good organizer of others in behalf of his need to know what the printed word said. Meanwhile, Reggie was a very able reader who had a great deal of trouble keeping his mind on the task at hand. His flightiness made it difficult for others to cooperate with him and he stood at the bottom of the groups’ choice of a partner to work with. The videotape revealed the pathos of Archie’s situation and his remarkable socio-cognitive skills in dealing with it.

At the beginning of the session, Reggie very deliberately refused to help Archie read the information they need to bake cranberry bread. Archie attempted to get the information from Ken who was sitting on the floor against the wall, putatively doing important record keeping work. Ken, it should be noted, was annoyed with Archie because he was not paying attention when Ken reviewed the instructions with the entire group. After helping Archie decode a few items in the recipe, Ken lost patience and told Archie to figure it out by himself. Reggie picked this moment to go to the bathroom, leaving Archie to figure things out on his own. He tried to elicit help from the girls, but they were engrossed in their ongoing projects and did not have much time for a boy. However, in their interaction they made it clear that Archie had failed to distinguish teaspoons from tablespoons and baking power from baking soda. Archie retreated to his corner of the table, bent over in confusion about what to do.

Reggie arrived back on the scene and saw that Archie was upset. “You upset, Archie?” he asked. Archie brushed his hand away and said, “Come on Reggie.” Next, the two boys focused on the instructions together, and Reggie began to read aloud as Archie started to carry out the actions (now that he had access to via Reggie’s ability to read). Reggie, in the meantime, was being a model student, under the control of his joint cake baking activity with Archie. The cake got baked. The following week, Reggie began by telling Archie that he would be cooperative, and the cognitive division of labor seen previously was replicated without special drama.

Conclusions about ecological validity

This work suggested that, by and large, the use of standardized cognitive-psychological experimental procedures implies that a closed analytic system is being successfully imposed upon a more open social/behavioral system. To the degree that behavior conforms to the pre-scripted analytic categories, one achieves ecological validity in the classical sense.

Yet our work, as well as studies by others, showed that even psychological tests and other presumably “closed system” cognitive tasks were permeable and negotiable. Insofar as the psychologist’s closed system does not capture the elements of the open system it is presumed to model, experimental results systematically misrepresent the life process from which they are derived.

The issue of ecological validity then becomes a question of the violence done to the phenomenon of interest owing to the analytic procedures employed. In this sense, we argued, ecological invalidity is built directly into the standardized test procedures themselves. We murder to dissect, as Wordsworth observed.

We had originally set out to answer a number of questions: Are the cognitive tasks that have been studied in the laboratory actually encountered in various classroom and club settings? Could we show similarity or differences in the behavior of individual children for tasks encountered in the different settings? Granting that the exact form of a given task would differ according to the context in which it occurred, could we specify how the context influenced the particular form of the task and the child’s response to it?

Any initial optimism that we could easily identify cognitive tasks outside of the laboratory and classroom and answer these questions was clearly wrongheaded. We could, with a lot of labor, identify cognitive tasks going on, but the idea that we could make within-subject comparisons across settings was clearly a formidable task. We managed this accomplishment in the case of Archie and Reggie to a limited degree, but the amount of labor required was enormous and the results, while illuminating, pointed to great difficulties in making a general practice of such comparisons. At the same time, we had made a great deal of headway on specifying why it is so difficult to generalize between laboratory experiments and psychological tests and everyday life. Their different social structures rendered such comparison implausible.

In trying to come to terms, theoretically, with what we observing, we found ourselves increasingly interested in the writings of Lev Vygotsky, which we had earlier viewed with extreme skepticism. At the same time, we had to come to terms with the theories growing out of the study of social interaction and discourse, which had been beyond our reach in the cross-cultural research. Both of these two closely related lines of theoretical development have remained signature features of Lab research in the years that followed. We will turn to a discussion of them in Chapter Five, both of which remained signature features of Lab research in the years to come.

Chapter Four Compositors: Michael Cole, Lois Holzman, Ray McDermott, Ken Trauppman

Chapter 4 References and Additional Resources

Back to Section Two Introduction and Chapter Three

Forward to Chapter Five