Our goal in this chapter is to give an account of the theoretical developments that occurred as part of the overall research program described in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7. This discussion should also be read in dialogue with Chapter 5, where our focus was on a theoretical analysis of the key concept of “context” as a means of beginning to understand the nature of “schooling as a context” and our initial, fragmentary efforts to come to terms with Vygotskian theory. Here, we summarize our efforts to expand our theoretical horizons to include the overall pattern that was emerging in the Lab’s cross-cultural research and the new evidence from research undertaken at UCSD, focused as it was on expanding the range of life’s activities we studied and on designing for learning and development to occur.

When we contrast the research conducted at Rockefeller with this first phase of LCHC research at UCSD, certain linked characteristics stand out. At Rockefeller, experimental methods played a large role in the research enterprise. We were, after all, seeking to discover the generality of the mixed psychology/anthropology (experimental/ethnographic) approach that we developed in Liberia. However, the Vai research had led us away from standard experimental procedures as models of presumably universal psychological process and instead led us to treat experiments as models of cultural practices. In the case of the Vai studies, this meant Vai practices of literacy. It was no accident that in the Yucatan work we came to understand psychological tasks as models of school practices. By the same token, the work on ecological validity included study of the kids in test situations as one point on a continuum from systems of interaction that were relatively closed and scripted, to those that were more free form and open.

The use of standardized tasks diminished when LCHC re-situated itself at UCSD. All of the research, whatever its institutional location, was focused at the level of cultural practices: literacy practices in the home, language practices in classrooms, small group instructional practices using computers as media of interaction, etc. When test-like elements entered this research, as they did in the Oceanside Project study of “same tasks in different school lessons” described in Chapter 6, the tests were ingredient to the instructional practices themselves, not external to them. It is noticeable as well that the studies at UCSD all had a distinctly “education-oriented,” practical focus, even Anderson’s research on literacy events in the daily lives of preschoolers outside of school, also discussed in Chapter 6. However, within this shared educational orientation, a distinct trend can be observed in which ethnographic research methods became increasingly more involved in the instructional process as it progressed. For example, the Moll and Diaz study on reading instruction began as an observational study of classrooms to see how children of monolingual and bilingual teachers differed with respect to the organization of reading. But results of the first phase of the research soon turned into a “teaching experiment” in which Moll and Diaz, directly inspired by Vygotskian ideas, conducted lessons to implement a strategy for language blending in the interests of reading acquisition.

A similar transformation took place in Riel’s after-school research on learning disabled children. It began as an extension of the cooking club research conducted at Rockefeller and ended up in the design of new instructional practices implemented in the after school hours. Centrally, the researchers also became the conductors of instruction in this research.

The same is true of Lab members who conducted the earliest research on the use of computers in classrooms. The focus of all of this research was on creating new cultural practices in which the social structuring of the activity using the special mediational capacities of computers could promote learning. The researcher often played the role of “teacher’s aide” in this research, present to support the teacher in adopting computer use in the classroom. But in supporting the teacher, we also saw the researchers taking on the de facto role of teacher insofar as they both designed and implemented cultural practice/activity-centered uses of computers as sources of data. To an increasing extent, strong distinctions between experimenter and subject, or objective/distant analyst versus co-constructor, were problematized and reflected upon.

All of these changes in patterns of interacting with the “subjects” of our research markedly transformed our attitude toward the children with whom we interacted and toward the social structuring that served as the “common context” for teaching and learning in activities that Lab members designed. It also reoriented our thinking about developmental and instructional theories more generally.

Context and Development

During the Rockefeller era, when we were conducting the Vai and Yucatecan research that deeply involved us in debates about cross cultural psychological research, it is not unfair to label the Lab’s position as “anti-developmental.” For example, Cole and Scribner wrote a paper on the hazards of applying developmental theories cross culturally on methodological grounds, but with a distinct bite to them. On methodological grounds, Cole and Scribner (1977) wrote:

“…we have been led to conclude that we simply cannot assess the general significance of a great deal of cross-cultural research that is nominally in the developmental mode. The problem is that deprived of the consistencies in performance across tasks, psychological functions, and behavioral domains which carry the interpretive power of the theory, we do not know how to generalize beyond the performances reported in individual studies … if we are correct in our analysis, there should be an explicit admission on the part of cross-cultural psychologists that their data are silent with respect to the developmental status of various Third World peoples. The ascription of childlike status to adults is too serious a conclusion to rest upon the evidence at hand” (p. 372).

Once we began to involve ourselves directly in instruction, we could not ignore chronologically related developmental differences. This circumstance further motivated us to deepen our knowledge of Vygotsky, Luria, and Leontiev, along with contemporary Western developmental research.

Addressing the Issue of Context-specificity

During the 1970s, the “cultural context” view proposed at the end of The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking (Cole, Gay, Glick & Sharp, 1971) diffused among a growing community of cross-cultural and developmental scholars. Generally speaking, our methodological critiques of the way others reached conclusions about cultural (and age-related) differences in performance were acknowledged as relevant and cogent, but our theorizing was dismissed as unproductive particularism. We could effectively criticize the use of then-prevalent research practices and their conclusions, but we had no viable theoretical alternative to offer.

Gustav Jahoda (1980) spoke for many psychologists when he wrote:

“Cole set out to track down the causes of this poor performance in some detail. Some of the empirical work was in fact undertaken, but most of his account consists of listing various possibilities like a seemingly endless trail vanishing at the distant horizon (p. 124)….[This approach] appears to require extremely exhaustive, and in practice almost endless explorations of quite specific pieces of behavior, with no guarantee of a decisive outcome. This might not be necessary if there were a workable “theory of situations” at our disposal, but as Cole admits, there is none. What is lacking in [the context-specific approach] are global theoretical constructs relating to cognitive processes of the kind Piaget provides, and which save the researcher from becoming submerged in a mass of unmanageable material” (p. 126).

This kind of criticism placed us in a position not unlike that of Franz Boas, whom we considered an important source of ideas. As we commented at the time, we found it significant that Jahoda’s criticism fit neatly with Marvin Harris’ complaints about Boas’ “historical particulars” or Leslie White’s concerns that Boas had doomed American anthropology to detail mongering.

Given the opportunity to summarize the state of research on culture in development in the early 1980s, we pointed out that Boas had never rejected the goal of a general theory of mankind built out of the elements of ethnography (LCHC, 1983). Rather, he had been over run with the enormity of the task of seeking to collect the data he deemed necessary. We had come to experience such difficulties ourselves!

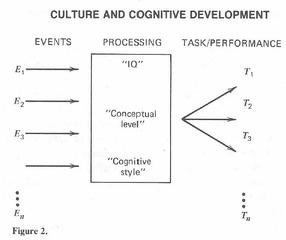

Most importantly, arguments about cultural/cognitive relations still leave us with the question — if human thought is primarily located in local domains, occurring “in context,” how is this context-boundedness overcome so that we do not have to encounter each of life’s experiences de novo? As we analyzed the situation, ideas about culture and cognitive development were suspended between two untenable extremes. On the one hand, we had “central processor” theories that assumed relatively encompassing changes, such of those of Piaget for whom cultural variation held little interest or of the still-popular cognitive style theorists whose sought generalized differences at the level of cultural configurations. On the other hand, we had theories that emphasized the primacy of the local organization of change processes that faced the difficulty of specifying how or when experience in one activity influences behavior as people move among activities in the course of their daily lives.

We diagrammed the “generalized change” account (where locally manifested changes are taken as symptomatic of more general changes) as follows:

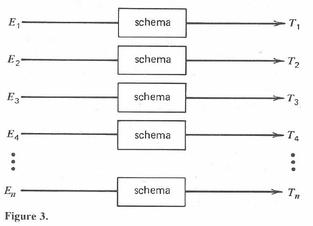

We diagrammed the antithetical, context specific, position in the figure below:

Neither pole of this specific/general binary is sufficient. The data from decades of work on human development overwhelming point to the variability of behavior within normal developmental stages and the idea that one’s experience is significantly discontinuous as one moves between and among the activities of everyday life, limiting the generality of the learning (limiting transfer, in the language of educational psychology).

David Rumelhart (1978) made this point with respect to adult reasoning. He argued that while schemas play a central role in reasoning:

“Most of the reasoning we do apparently does not involve the application of general-purpose reasoning skills. Rather it seems that most of our reasoning ability is tied to particular schemata related to particular bodies of knowledge” (p. 39).

Jean Mandler (1980) pointed out an implication of this view that seemed to describe both cultural differences in thinking and the difficulties engendered by the use of standardized psychological testing in cross-cultural research when she remarked that behavior in familiar and unfamiliar situations differs because:

“…familiar situations are those for which schemata have already been formed and in which top-down processes play a larger role” (p. 27).

As Jean Lave (1988, p. 173) commented a few years later, despite the importance of within-context learning as a starting point of learning, activity/context-specific approaches to cognition are still obligated to account for the sources of continuity across settings in everyday life. The ability to supersede one’s context was, after all, both central to Vygotsky’s theorizing about the role of higher psychological functions among humans. It is also an obvious feature of everyone’s daily experience.

The solution we offered was to keep in mind two culturally organized social processes that operate in conjunction with each other in the course of children’s experience in life: the organization of activity within contexts (in the home, in church, on the way to the drug store, etc.) and the social mechanisms of context selection through which adults distribute children’s time in the network of socially linked activities that constitute individual experience.

Many scholars influenced our thinking in this regard. A central cog in our approach was suggested by Bea Whiting, who began her life’s work focused on how socializing adults and older kin or their surrogates “mold” children’s personalities within activity settings. Whiting (1980) characterized this molding process in the following terms:

“Each setting is characterized by an activity in progress, a physically defined space, a characteristic group of people and norms of behavior – the blueprint for propriety in the setting. Thus a child moving from the classroom to the playground interacts with adults and peers in different manners. The standing rules for these settings do not prescribe the same type of social interaction” (p 103).

This thinking placed her very much in line with ecological psychologists such as Roger Barker and with our own context specific approach (Barker & Wright, 1956). To explain how within-activity molding breaks free of its context, Whiting initially relied upon the notion that transfer of local knowledge results from within-activity learning. In her words:

“…our theory hypothesizes that the habits of interpersonal behavior that one learns and practices in the most frequented settings may be overlearned and may generalize (transfer) to other settings and to other statuses of people” (p. 103).

She introduced the second form of influence when she noted that adults are responsible for many of the decisions about what sorts of activities their children participate in. As a consequence:

“Many of the age changes that have been reported in the literature on child development may be the result of frequenting new settings as well as gaining new physical and social skills” (p. 111).

We characterized Whiting’s new approach as a proposal for a “context-selection” mechanism because it helped us to focus on specifying the influences working in the various social networks of activity/pathways through life that each child experiences. Based on these ideas, we proposed as an alternative way of thinking about transfer that we called a “Cultural-Practice Approach to Transfer.” In adopting this phraseology we were attempting to combine several ideas at once:

- Emphasize the sociocultural organization of learning within the settings that children inhabit. What sorts of “zones of proximal development” do they represent in as much of their variety as possible?

- Study the sociocultural selection mechanisms that placed children in various activities.

- Wherever possible trace the socially organized linkages between activities and their participants.

- Pay attention to the mediational means (language, writing were our focus) that are shared across activity settings.

- In Boasian fashion, try to understand the ecological and historical circumstances within which the existing networks of activities exist.

This approach committed us to understanding the mechanisms of within-activity setting change and induced us to pay a lot of attention to the sociocultural organization of the actions occurring there. It also allowed us to combine the study of diachronic change over the course of ontogeny with a study of synchronic variability in the range of contexts/activities in which the newly forming psychological functions emerge. In this process, the older, more experienced participants in the new activities that children enter into “create transfer” in their efforts to incorporate the newcomer.

Based on the evidence available at the time, we concluded that, in several important ways, transfer is arranged by the environment. This shift of focus does not so much solve the transfer problem, a dissolve it. Overlap in environments and the societal resources for making palpable areas of overlap between settings are major ways in which past experience carries over from one context to another.

In support of our arguments we offered work such as that conducted by Jean Lave, in particular her work on the repetition and redundancy both within and in transit between contexts that characterize the texture of everyday life (1979). Where contexts overlap (at a tailor shop in Monrovia, Liberia or shopping in a market in Monrovia, California) the problem of transfer is minimized and multiple opportunities for dealing with the unexpected are provided. We pointed to language as the most pervasive and arguably the most important carrier of information from one context to another. In language, the routineness and repeatedness of everyday life are encoded in the lexicon, reinforcing analogy-supporting data provided by the physical characteristics of routine events. Consequently, when language encodes the relevant relation between distinct contexts, the contexts are no longer distinct; no transfer as an individual invention is required.

Designing Learning Environments

Our writing on the issue of context specificity and theory building based on cross-cultural work was written at the same time that were we seeking to improve and better understand our ongoing research practices in the U.S. Recall that during the period under consideration, all members of the Lab were activity involved in using the principles developed on the basis of our prior cross-cultural and cross-setting research (summarized in Section 2) to design activities that would promote the learning and development of children.

If the study of culture and cognitive development required both within- and between-context relations to be studied, we needed to design in ways appropriate to the research questions at hand. Moreover, we needed to do this in varied institutional settings, not just the school classroom. This theoretical necessity gave us a way to recuperate our earlier theoretical writings on formal and informal education. This topic, fortunately, acted as a major factor in the “between-context” half of the equation in the historical circumstances in which we found ourselves.

This tendency is found both in studies that featured the use of computers and those that did not. So, for example, in the Anderson et al. work on literacy events, attention was paid to the many ways in which literacy events were triggered by interaction between home and community – doing the monthly bills at the kitchen table, checking the TV guide for programs, reading the bible at home or at church are typical examples.

The Moll and Diaz research on bilingual reading instruction hinged crucially on the fact that they conducted the research in a school with two different reading regimes, each with their own internal practices of mixing oral and written language. Their research documents the way in which institutional arrangements prevented the teachers from meeting each other, so that while the children moved from one setting to the other, knowledge of their reading abilities in Spanish and English did not. In this case, a “phonics before comprehension” ideology combined with differential knowledge of Spanish to make a difficult situation worse for all involved.

The Oceanside School Project was directly founded on the between/within context strategy because it was all about the problem of what it means to talk about “the same task in a different context.” In this case, the Piagetian formal operations combinatorial problem served as the “tracer” element across its instantiations, ranging from carefully simulated, rather standard individual testing through classroom lessons to a weekend hiking club that had to put together a different combination of meals for each hike. This strategy provided unique evidence of the ways in which the level and kinds of within-activity support that the teacher provides is linked intimately with her/his ideas about what the children will need to be able to do in a later part of the curriculum about which the children have no idea as yet.

It took a number of sessions for many of the children participating in the reading activities at Field College to realize that the group reading tasks were actually related to each other. It also took a while for them to understand how to keep in mind the fact that they would later be asked to display what they had learned during instruction in a new activity called “the quiz.” Once that realization took hold, the children were in a far stronger position to “transfer” the reading they had done to the quiz using their own questions and suggestions as the material to be read and understood.

Providing Dynamic Support: Enter the Zoped

During this time, excitement about computers, their apparent power to create rich learning/teaching opportunities, and their distance networking potential became a focal point for thinking about learning and instruction. It is in the various strategies used to instruct kids from different ethnic and social class neighborhoods around San Diego, that Vygotsky’s notion of a “zone of proximal development” played a crucial role in our thinking.

As the empirical studies described in Chapters Six and Seven indicate, every project struggled in its own way with creating educational interactions where children obtained “dynamic support” — the general concept carried over by Jim Levin from our colleagues in CHIP. Mehan and Riel (1986) write:

“Dynamic support refers to the process of systematically decreasing amounts of assistance provided to novices as they progress in expertise and gradually assume parts of the task initially accomplished by an expert. In a properly arranged teacher-student-computer environment, it is possible to create the kind of dynamic support necessary to improve students’ writing dramatically” (p. 9).

Riel’s research on language disabilities showed how laptop computers could provide dynamic support. She found that children with language handicaps had greater difficulty in making efficient problem-solving decisions when playing computer games than did a group of students with normal language development. In a follow-up training study, Riel modified the computer so that at first, most of the game parameters were controlled by the computer. This support was gradually withdrawn as the players’ skill increased. After several weeks, the game performance of both groups was quite similar. The computer had been used to construct a “zone of proximal development,” or “dynamic support.” It provided training in a variety of systematic, self-regulatory, problem-solving skills as the children learned basic materials.

Those colleagues who joined UCSD from time spent at Rockefeller were focused on a notion of dynamic support that was already heavily infected by Vygotsky, in particular his idea that in using culturally mediated activity, one could produce teaching/learning circumstances where teaching could promote children’s overall development. Importantly, in our collective paper about culture and development focused on cross cultural work (LCHC, 1983), we gave the notion of Zone of Proximal Development a place of privilege in suggesting how to evaluate the within-context processes of change we were seeking both to promote and to document.

Locally, we began to refer to the notion of Zoped, which is a synthesis of the word “Zo” in Liberian English (meaning shaman) and a root of the term, pedagogy. It was coined as a way of expressing the idea that a successful Zone of Proximal Development involved both sound pedagogy and a little magic. Mixing play and “serious instruction” is a manifestation of this notion.

For Luis Moll and Esteban Diaz, the forms of language mixing that they invented on the spot when they discovered the odd goings-on in the classroom were the application of the notion of Zoped. They did not offer help along a single dimension; the re-mediated the process of reading and oral discussion created a qualitatively new situation that allowed them to disentangle the problem of speaking in accent-less English from the problem of being unable to read. In the process, they created a whole new zone of possibilities for the children.

At Field College, our research focused on the somewhat exotic forms of reading activity that Peg Griffin invented to deal with antsy kids in a difficult-to-control afterschool setting. This work provided an example of our thinking about Zopeds that emphasized the need for understanding how learning instruction for failing children might be organized so that learning leads to development. In this case, a scripted small group activity was organized in which the children had a variety of roles to play in the process of making sense of text and the activity was organized as a kind of small group game (see Cole, 1995).

An unusual departure from both typical examples of change in Zopeds extant in LCHC work employing the notion of a Zoped was that it took place not in dyads, but in groups of three or more people. This tendency is seen vary clearly across the broad range of studies of computer-mediated educational activities, whether designed for in school or after school use.

Often these groups appeared as trios of participants – an adult and two children huddled around a computer game, or small groups fluidly carrying out different roles in preparing a “computer chronicle” story to exchange with far off children. This form of small group organization was particularly effective in classrooms that were organized using “activity centers.” In such settings, collaboration around joint computer-based problems contrasted strongly with the then-prevalent approach of using computers either as a reward for finishing an academic task quickly (using edutainment games) or the “utopian” vision of an Apple 2 on every desk in a regular classroom in which norms of group instruction combined with individualized learning were pervasive. At other times, such as in the instructional activities designed by Peg Griffin, two or three adults and half a dozen or more children were engaged.

So much has been written about these issues in the subsequent 30 years that we cut short our summary at this point, knowing that by following the various links provided within the narrative, readers can purse topics of their own choosing. Like all productive ideas in the social sciences, inquiry yields not only clarity, but many new questions, as well as not-a-little confusion. These topics resurface, naturally enough, in later sections.

Chapter Seven Compositors: Michael Cole, Bud Mehan

Chapter Eight References and Additional Resources

Back to Chapter Seven

Forward to Section Four Introduction