The research described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 spoke to ongoing debates in experimental, developmental psychology about age-related changes in cognitive processing. It illuminated various procedural factors involving the content and modes of implementation of standard tasks across groups. We were especially dubious of “higher/lower” comparisons based on standard test procedures.

The research described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 spoke to ongoing debates in experimental, developmental psychology about age-related changes in cognitive processing. It illuminated various procedural factors involving the content and modes of implementation of standard tasks across groups. We were especially dubious of “higher/lower” comparisons based on standard test procedures.

At the same time, and sometimes in combination, we used observational techniques to investigate “home culture” patterns of language use in comparison with classrooms. We discovered, as others had before us, that psychological tests are constituted in a highly constrained manner. This made the results obtained using them suspicious, particularly when one tried to draw generalizations from the test to the less constrained circumstances of, say, a cooking club. The borders of their ecological validity were poorly mapped, and when mapped, they appeared to be suspect.

Understandably, these observations made it important for us to broaden the scope of our theoretical framework to be able to make systematic sense of what we were seeing. While were conducting the various research projects described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, the Lab met collectively twice a week. One of these meetings was devoted to reporting on and writing about the ongoing research, asking for advice, and trying out ideas on one another. The other meeting was devoted issues of general concern across all the projects. Often attended by colleagues from other interested groups in New York and by visitors from afar, it was at these seminars that we read widely across the social sciences in search of alternative ways of thinking about the relation of culture and psychological processes.

This practice gave rise to collaborative publications under the name of LCHC. Each of the articles that came out of our meetings addressed the larger theoretical and methodological controversies that had to be dealt if there was to be any chance of a productive combination of anthropological and psychological approaches. Two of these papers, published simultaneously in the Annual Review of Anthropologyand the Annual Review of Psychology, were directly focused on the mutual relevance (and lack thereof) of extant writing on the question of how human psychological processes are related to the cultural organization of their activities.

In What’s Cultural about Cross-Cultural Cognitive Psychology(LCHC, 1979), we posed the following question to psychologists:

“In what sense(s) does culture enter into the formulation of problems, the identification of independent variables, the observational techniques and, hence, the dependent variables of cross-cultural, cognitive research?” (p. 146).

Our answers posed tough problems of methodology for cross-cultural psychology during the 1970s. First, they raised the thorny issue of how to specify and quantify independent variables. Second, they prompted questions about the validity of the data that served as dependent variables.

With respect to the independent variable we (LCHC, 1979) argued:

“In so far as there is agreement (for example, among anthropologists to whom the psychologist typically turns as the source for a definitional warrant) those who are concerned with the study of culture emphasize the patterning of ideas, institutions, and artifacts produced by the group in question. Recognition of the difficulty that such patterning poses for the psychologist is widespread in principle, but very difficult to apply in particular circumstances” (p. 146).

With respect to the dependent variable, our argument was articulated clearly by Florence Goodenough (1936), an early pioneer in the conduct of cross-cultural research:

With respect to the dependent variable, our argument was articulated clearly by Florence Goodenough (1936), an early pioneer in the conduct of cross-cultural research:

“Now the fact can hardly be too strongly emphasized that neither intelligence tests nor the so-called tests of personality and character are measuring devices, properly speaking. They are sampling devices. . . . we must also be sure that the test items from which the total trait is to be judged are representative and valid samples of the ability in question, as it is displayed within the particular culture with which we are concerned” (p. 5).

We hardily agreed. Our “ethnographic psychology/experimental anthropology” approach was intended to follow through on this precise point. The big challenge, we asserted, was to figure out how to collect samples as they are displayed within a culture, and most cross-cultural psychology did not achieve this goal.

To the anthropologists we argued that, despite long traditions of talking about the modes of thought that are characteristic of different cultural groups, they were not likely to be accepted by cross-cultural psychology, which was fighting off challenges to its legitimacy arising from its methodology. The dominant traditions of experimental psychology require far better specification of the task the subject is engaged in and far better specification of the constraints on modes of response (the “experimental procedures” that enable one to score responses) than anthropologists can generally provide (see our page on cross cultural research). Such specification was necessary to suit the canons of scientific psychologists for whom “the task” is a combination of a goal and the associated constraints on modes of achieving it. However, anthropologists offered a sobering set of questions concerning the validity of some of psychology’s primary techniques of measurement. They asked: how do you know the subject’s goal, especially when one is dealing with people from different life experiences?

Insofar as anthropologists sought to use research methods that emulated psychological practice (so called “white room” ethnography), they had less to say about traditional anthropological concerns related to cognition in everyday life. This limitation was especially true when conclusions about cultural differences in thought processes were claimed to be about “what is going on in the head” — an unfortunate phrase that was began to crop up in anthropology, just as the cognitive revolution was encouraging such talk in psychology.

The result, as we judged it at the time, was a standoff. The situation was stated particularly well by S.F. Nadel (1951), a psychologically trained anthropologist:

“[U]nless the relations between social and psychological enquiry are precisely stated, certain dangers, all-too-evident in the anthropological and psychological literature, will never be banished. Psychologists will overstate their claims and produce, by valid psychological methods, spurious sociological explanations; or the student of society, while officially disregarding psychology, will smuggle it in by the backdoor; or he may assign to psychology merely the residue of his enquiry-all the facts with which his own methods seem incapable of dealing” (p. 289).

The deeper our seminars delved into the complexity of the 100-year-old struggle to resolve the relevant disciplinary divides, the more we appreciated just how difficult it would be to actually construct an amalgam of experimentally oriented anthropology and a culturally oriented psychology. Each of the individual projects described in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 were intended to contribute in one way or another to this project. We were using experimental psychological methods in the study of literacy and schooling in the international research. At the same time, we used analogous methods in studies of dialect effects, vocabulary differences, social setting, across population variations of concern in New York City.

Given the stage of the work at the time, we have decided to organize this chapter around two issues that we began to confront. The first was the issue of context, a polysemous concept that was then widely used by anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists. The second was to develop a theoretical framework that could encompass the phenomena we were encountering. Addressing both of these issues seemed essential if we were going to work out a common methodology that spanned the disciplinary chasm our research had led repeatedly brought us to. Finally (and crucially), related to these two issues was a reconsideration of the “consequences of schooling” as it appeared to us in light of both our international and domestic research.

Context by Any Other Name

As should be evident from Chapter 1, our early invocations of context in the Liberian research of the 1960s and 1970s used the term in a common sense if fuzzily conceived way. Whether referring to “a task in its context” or “the cultural context of learning,” our usage was a poorly differentiated means of claiming that there was something special and psychologically important about the setting or environment within which the psychological experimentation occurred. Context could refer to familiarity with words or to ways of understanding the interview and the testing circumstances themselves. It could refer to cultural norms for appropriate age or gender conventions that applied to the participants involved in interviews and experiments as well as to different social settings. Almost anything that influenced the performance of interest could be invoked as relevant to “the context.”

We were not alone in this respect. The literature in psychology and allied social sciences was littered with references to research in “encounter group context,” “emotional context,” “linguistic context,” “physical and social context,” and the “context of a psychiatric center.” It was a regular Borges “Chinese menu” of definitions.

During the 1970s, Lab members and colleagues who shared our concerns worked to better specify what we meant by context, drawing upon classical scholars in each of our respective fields and upon our own experience. There were hard questions to be dealt with: Why and when could entities as wildly different as an encounter group or an emotion count as context? Why and how would changing the frequency of particular words change a context? What did such uses of the term share in common with the idea of culture or schooling as a context (Cole, Dore, Lave, Roth & Scribner, 1977)?

Then, as now, the term context in ordinary discourse was treated more or less synonymously with terms such as situation, environment, or activity. Goodwin and Duranti (1992) summarize what these approaches had in common:

“When the issue of context is raised it is typically argued that the focal event cannot be properly understood, interpreted appropriately, or described in a relevant fashion, unless one looks beyond the event itself to other phenomena (for example, cultural setting, speech situation, shared background assumptions) within which the event is embedded…The context is thus a frame (Goffman, 1974) that surrounds the event being examined and provides resources for its appropriate interpretation… The notion of context thus involves a fundamental juxtaposition of two entities: (1) a focal event; and (2) a field of action. (p. 3)”

Beyond an agreement that the “juxtaposition of two entities” is at the center of the issue of context, scholars working within different disciplinary traditions disagreed a good deal in how to specify these entities and about the consequences of their juxtaposition. This approach to interpreting context implies that the phenomenon of interest is not a thing in itself, or even a trait. Instead, context is a person-environment interaction, where both sides of the duality are difficult if not impossible to specify in objectifiable and “context free” terms, let alone measurements.

Psychologists’ Approaches to Context

A recognition that behavioral performance on psychological tests/tasks is contingent on “contextual factors” was beginning to take root in many branches of psychology, ranging from personality theory to experimental studies of adult learning and developmental psychology.

Within personality psychology, David Magnusson and Norman Endler brought together two decades of research by scholars concerned with the idea of “stable” personality traits in light of the apparent variability of such traits according to context. The spirit of this enterprise was captured in the title of the Magnusson and Endler book, published in 1981, Toward a psychology of situations: An interactional perspective. Central to their line of thinking was a distinction between two research strategies. The first line of research sought to describe and measure contextual environments “as they are,” as stable structures in the world. It pursued greater specificity by creating ways to identify “variables” that would identify relevant aspects of the environing context that were though to influence the psychological phenomenon of interest (free recall performance, for example). This approach invited researchers to classify such factors in order to make statements about their relative contributions (e.g., cognitive development in the context of poverty, where measures of SES are proxy variables and cognitive tests are the dependent variables).

The second prominent line of research, using the notion of context, sought to understand environments “as they are perceived,” that is, as partially psychologically constituted (and thus much more difficult to specify in terms of objective, stable criteria). From this latter perspective, the task/context relationship results from the interaction of these two “juxtaposed entities.” It eschewed attempts to treat context as an explanatory concept to be used in relation to the ordinary “independent-dependent” paradigm of mainstream psychology. Rather, it focused on the processes of interaction “within the context” that made the focal processes of interest available for analysis.

One of the major influences on our thinking about these alternatives was Gregory Bateson. In his book, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Bateson (1971) distinguished these two different ways of using the term context, focusing on how they had appeared in his own work:

“In the essays collected in Part III, I speak of an action or utterance as occurring “in” a context, and this conventional way of talking suggests that the particular action is a “dependent” variable, while the context is the “independent” or determining variable. But this view of how an action is related to its context is likely to distract the reader—as it has distracted me—from perceiving the ecology of the ideas which together constitute the small subsystem which I call “context.” This heuristic error—copied like so many others from the ways of thought of the physicist and chemist—requires correction. It is important to see the particular utterance or action as part of the ecological subsystem called context and not as the product or effect of what remains of the context after the piece which we want to explain has been cut out from it” (p. 338).

This way of thinking fit well with our experiences in the after school clubs. At the same time, many of the issues we sought to address were caught up in national discussions about the “causes and consequences of poverty” (or ethnic difference, or school success, or…). Under these circumstances, we could not opt for one approach to context at the exclusion of the other, any more than we could turn solely to psychology or anthropology to think about culture and development. The various mixtures of methods we devised to come to grips with the meanings of “context” and their presumed consequences are illustrated by the different projects Chapter 3 and Chapter 4.

One widely adopted view of how to get an analytic grip on the concept of context in psychological research was put forward by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979) in his early book, The Ecology of Human Development (See Cole’s forward). Bronfenbrenner’s formulation gave rise to the ubiquitous “concentric circles” illustrations of the idea of levels of context that represented the state of most psychological thinking at the time. This general line of thinking, implemented in a variety of ways, has played a large role in studies of social class, ethnicity, and other “social addresses” that can be correlated with some aspect of human development.

Although ubiquitous in everyday language and useful for many purposes, there are some crucial shortcomings of the metaphor of context as embedded layers of structure. For one thing, as Bateson pointed out, the concentric circle interpretation of context encourages the notion that causality runs from more inclusive levels “downward” (“macro to micro”), which has the unfortunate feature of denying agency to the individual who is located at the innermost of the context’s elements. It also sidesteps the influence of cultural practices in shaping the more inclusive social environment. Nonetheless, such usage appeared in our own work and that of others, just as it had in Bateson’s.

Context in American Developmental and Experimental Psychology

Cross-cultural work that emphasized cultural contexts (however defined) began to gain the attention of experimental psychologists, some of who were interested in the process of cognitive development and others of whom worked with adults. Many developmentalists focused on children from age 3-5, particularly their stages of cognitive development as gauged by the use of Piagetian tasks. This was the age when children were thought to be egocentric, to experience difficulty distinguishing fantasy from reality, and to be incapable of causal reasoning. However, in study after study, what seemed like minor modifications of Piagetian procedures produced the “missing” stage-specific competence and 3-5 year olds suddenly appeared to think like 8-11 year olds.

In an Annual Review of Psychology article on cognitive development, Rochel Gelman (1978) succinctly explained the theoretical implications of the cross-cultural evidence to theories of learning and development:

“A similar argument motivates the design of cross-cultural studies of cognition conducted by Cole and his associates, who convincingly contend that we will best understand what is common between and what distinguishes the thought processes of different cultures as we uncover the task and context variables that block success, where success is defined from the experimenter’s point of view. It is not just a matter of methodological concern that should motivate the search for the answer as to what constitutes the child’s definition of the experimenter’s ‘game.’ When we know how to ask the questions, design the tasks, and engage the preschooler, we will know much more about the nature of early cognitive development” (p. 326).

Simultaneously, experimental studies were producing “developmental shifts” among adults through the kinds of manipulations that seemed to echo in the cross-cultural and developmental literature. For example, two repeated findings in the cross-cultural literature were that schooled people were more likely to respond logically to syllogisms than their non-educated age-mates who responded on the basis of personal experience and that non-educated people associated words with each other functionally while their educated peers responded in terms of logical categories. However, “cultural deficits” in local thinking and categorization using just these kinds of tasks were found among American college students by varying the particular contents of the task. In each case, changes in the cultural content of the task mimicked the cross-cultural findings markedly changing the college students’ performance from “adult/logical” to “childlike/primitive.”

The cross-cultural research community greeted this kind of evidence less favorably than developmentalists conducting experiments with children working in the U.S. While acknowledging the validity of our critique of empirically gathered data (this critique had been voiced before – we were following in a long tradition, as indicated in Section 1), our cross-cultural colleagues faulted us for lack of a positive theoretical program beyond the statement that “everything depends upon context.”

This criticism is clearly articulated by Gustav Jahoda (1980) in a handbook chapter devoted to cross-cultural research:

“Cole set out to track down the causes of his poor performance in some detail (Kpelle rice farmers had failed to communicate sufficiently discriminating attributes of the to-be-identified objects). Some of the empirical work was in fact undertaken, but most his –sic] account consists of listing various possibilities like a seemingly endless trail vanishing over an endless horizon…[This approach] appears to require extremely exhaustive, and in practice almost endless explorations of quite specific pieces of behavior, with no guarantee of a decisive outcome. This might not be necessary if there were a workable “theory of situations” at our disposal, but as Cole admits, there is none. What is lacking in [the context-specific approach] are global theoretical constructs relating to cognitive processes of the kind Piaget provides, and which save the researcher from becoming submerged in a mass of unmanageable material” (p. 124-126).

The Vai research had solved this problem by making differential engagement in cultural practices within a given cultural group the focus of its analysis. In that case, the practices in question involved the uses of literacy. In this approach, the experimental procedures modeled those practices and allowed compelling comparisons. However, print-mediated practices do not exhaust the range of potentially important life domains. Therefore, the general challenge remained, and it clearly was not restricted to cross-cultural research. The status of the evidence about “context variables” in the literature was, and remains, a matter of intense debate not only in mainstream developmental cognitive and learning psychology but theories of personality as well.

Context in American Sociology and Anthropology

At the same time that Lab members were approaching the issue of context and concerns about the ecological validity of ordinary experimental tasks from a grounding in experimental psychology, they were also actively engaged with researchers who came out of the traditions associated with interactional sociology, ethnomethodology, and discourse analysis.

Context as an Interactive Accomplishment

interlocking patterns like this one were common examples used to explain what was meant by “continuous process or multidimensional interaction (feedback) between the individual and the situation that he or she encounters”

Importantly, a shared core assumption that united those coming from a psychological perspective with those whose point of departure was the social order was that “[a]ctual behavior is a function of a continuous process or multidimensional interaction (feedback) between the individual and the situation that he or she encounters” (Magnusson, 1977, p. 968). This idea pinpointed a great many of our concerns about treating cognitive tests as non-interactive, stimulus-response terms. This difficulty was most forcefully evident in our work in the after-school clubs.

In working through these issues and seeking to get to the details of this interactive process, we were greatly influenced by two scholars who have continued to play an essential role in the thinking of LCHC since its inception. The first is Ray McDermott, who was a member of the LCHC team that took on the ecological validity question. The second was Bud Mehan, who became a member of LCHC when it subsequently moved to California, but with whom we began to interact actively while still at Rockefeller.

The Analysis of Differential Teaching Contexts in Classroom Lessons

In his PhD thesis and later writings, Ray McDermott argued that people are environments for each other in interaction. In a 1978 annual review article on interactional approaches to the social organization of behavior, he and David Roth focused on describing the ways “people organize concerted activities in each other’s presence.” They wrote:

“We . . . assume that a person’s behavior is best described in terms of the behavior of those immediately about that person, those with whom the person is doing interactional work in the construction of recognizable social scenes or events” (p. 321).

McDermott’s study of the differential learning opportunities afforded to students in a top and bottom reading group in an elementary school classroom exemplifies this point of view. It simultaneously demonstrated a central concern of “microethnographers” – that unequal educational opportunities are provided to children who are perceived as less able in a variety of educational settings or “contexts” (classroom reading lessons, IQ tests, and counseling sessions).

Ray’s writing during the 1970s provided a particularly compelling description of the social construction of children’s success and failure in learning to read. In doing so, he encouraged us neither to applaud students solely for excellent school performance nor to blame poor school performance on the personal characteristics of students entering school. Instead, we were forced to recognize that school success and failure are achievements that must each be understood in terms of each other. School failure is not a simple absence of school success, but an actively constructed option for all children. School failure does not unfold naturally. Instead, it takes work on the parts of everyone in the system.

Constructing Students’ Intelligence in Testing Interaction

Bud’s early research (1973, 1974, 1978) spoke directly to the analysis of the dynamics of standardized IQ testing situations, revealing yet another educational context that contributes to unequal educational opportunities. It also provided critical support for our efforts to understand the relationship between people’s performance on cognitive tasks and the socio-cultural contexts of those tasks, as discussed in Chapter 2.

Mehan analyzed videotapes of the social interactions between educational testers and children during the administration of IQ tests. He reported that the intelligence that we attribute to children as their personal possession actually emerges from the social interaction between the tester and the student. The instruction manual directs testers to administer tests in a rigidly specified, routinized way. They are to ask a question, pause, let students respond, record the answers, and go on to the next question. When he examined actual tester-student interactions, however, he got a different, much more social-interactional view of the tested performance.

For example, a question on the Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-R) in use at the time of Mehan’s study was: “What is the thing to do if you lose a ball that belonged to one of your friends?” After the tester asked this question in one of the testing sessions Mehan studied, the following exchange took place:

Student: “Might get another one for her”

Tester: “Yeah. Is there anything else you might do?”

(That is, instead of asking the next question, the tester questioned the student’s answer. The tester’s intervention led the student to modify his answer.)

Student: “Tell her the truth.”

Mehan found that depending upon whether a tester recorded the first or subsequent answers after these interventions, a student’s test score varied by as much as 25%.

Overall, Bud’s close analysis of tester-student interaction and test scores, produced a different view of intelligence, student identity, and educational opportunity than an examination of test scores alone. Intelligence test scores, when presented as a numeral, are a product that is divorced from the social means that produced them. Those social means are not standardized. They are replete with evidence that marginalized students received less “wiggle room” in their answers, less follow-up of the kind that leads to higher scores.

Subsequent decades made clear that the issues we were raising about task and context (focal event and field of action) at LCHC in the 1970s were part of a much larger stream of work among social scientists to deal with dualistic notions of context. All of this broad range of issues would come to occupy a central role in the research that was subsequently undertaken when LCHC moved to UCSD.

Reconsidering the Cognitive Consequences of Schooling

Nearly as soon as we had begun to publish the results of our research on the role of schooling in tested cognitive ability, people began to ask us what processes taking place in the classroom could lead to the differences in cognitive performance we observed in our experiments. After all, while it proved possible in many cases to track down the causes of performance differences, even when great care was taken in preparing materials and procedures, people who had no experience of schooling seemed to perform quite differently than their schooled counterparts. How were we to interpret these results? One way of evaluating our developing views about the cognitive superiority of schooling is to consider two articles. The first was written during the Rockefeller years by Scribner and Cole with our thoughts as a result – a decade later – of the Vai and Yucatecan work.

The cognitive consequences of formal and informal education

Taking the accumulated evidence of the prior research, Scribner and Cole (1973) began from the premise, which was based on their Liberian research, that what all of the cultural groups they studied demonstrated the capacity to remember, form concepts, operate with abstractions, and reason logically (p. 541). Nevertheless, they ventured a guess, also based upon the Liberian research, that there was a potential difference in cognition favoring those who had attended school. They summarized the extant data in the following terms:

Cole and Scribner in Liberia

“…unschooled populations tended to solve individual problems singly, each as a new problem, whereas school populations tended to treat them as instances of a class of problems that could be solved by a general rule.

[For example] adults were given a series of classification problems based upon the familiar Kpelle distinction between forest animals and town animals. Solving the second problem (in the series) was no faster than the first, and no faster than the performance of a control group that had completely different instances of the two classes” (p. 554).

What made this finding puzzling was that independent ethnographic and linguistic evidence obtained from the same people indicated that they were familiar with, and commonly made use of, the very same classes built into the materials and procedures of the experiment. They were failing to use information that they had manifested in other, similar circumstances. We wanted to know why.

One potential answer focused on the distinctive nature of schooling as a form of experience. Along with many others writing at the time (e.g., Bruner, Greenfield et al, 1966), Scribner and Cole (1973) argued that:

“…school represents a specialized set of educational experiences which are discontinuous from those encountered in everyday life and that it requires and promotes ways of learning and thinking which often run counter to those nurtured in practical, everyday life” (p. 553).

In addition, they joined with Bruner and others in pointing to the unusual role of language in mediating experience as the key to the observed “cognitive consequences”:

“It is self-evident that when linguistic forms carry the full burden of communication, the amount of information available to the learner is restricted…. As visual and other modalities of information [available in many settings] disappear in the classroom, the skills for processing them become irrelevant to the learning situation and become impediments… This conclusion fit perfectly with Bruner’s focus on the way in which school-based talk is “out of context” (p. 556).

But they also drew a further implication:

“What is special about learning out of context in school is that the child is asked to learn material that has no natural, that is, non-symbolic context…this independent learning of techniques or instrumental skills, apart from the ends to which they will later be functionally related does not seem to have many parallels in everyday life…This is another sense in which school learning can be considered ‘out of context” (p. 556).

Unlike Bruner and other developmentally oriented colleagues, however, Scribner and Cole did not interpret test results as evidence that schooling is required to develop the more advanced, generalized cognitive stages that were popularly invoked at the time. Rather, they argued that the differentiating factor for schooled and non-schooled people in their tested performance was that the two populations have different amounts of practice in exercising the skills learned in the context of schooling:

“Given extensive participation in concept formation on a purely linguistic level, it is not surprising that school populations tested in a variety psychological tasks give fuller and more accurate verbal descriptions of their classifying operations and rules of solutions than do their unschooled counterparts” (p. 557).

By the same token, it should be no surprise that school populations treated successive problems posed to them by an experimenter as instances of the same class of problem. Sequence problems of the same class were precisely the content of the schooling experience to which the non-schooled had no exposure. This is where matters stood as LCHC was getting organized at UCSD.

Cultural Practices and Cognitive Consequences

The subsequent research carried out among the Vai in Liberia and the Maya in the Yucatan, combined with research conducted in New York, deepened our skepticism about the nature of the cultural differences associated with differences in the test performances of people with varied schooling experience.

The Vai research, as we recounted in Chapter 3, enabled us to put cultural practices at the focus of our attention and to treat experiments as models of those practices, not as measures of de-contextualized cognitive abilities. The Yucatecan research, while confirming and extending evidence that levels of performance on our cognitive tests varied as a function of years of schooling (e.g., years of practice solving school-like tasks), only served to reinforce our earlier conclusion: Our experiments were good models of schooling practices, but the research we were conducting was mute regarding any general cognitive consequences of schooling.

Toward the end of the Yucatecan monograph, Donald Sharp, Mike Cole, and Charles Lave made the following speculation about the possible usefulness of schooling even if it did not produce generalized changes in intellectual abilities:

“…the information-processing skills which school attendance seems to foster could be useful in a variety of tasks demanded by modern states, including clerical and management skills in bureaucratic enterprises, or the lower-level skills of record keeping in an agricultural cooperative or a well-baby clinic” (p. 84).

It would be decades before this idea was put to the test, much less shown to be correct and expanded upon in a manner that addresses contemporary social policies that promoted universal education throughout a good deal of the world (LeVine et al.).

There remained an unnoticed factor in the search for objective and ideally quantifiable measures of contextual variables and cognitive consequences. While, as many observed, rural Third World children who had been to school performed on tests more like their American counterparts than their age mates who had not attended school, these same children’s failure in school was the very reason that had brought psychologists with diagnostic tests to Liberia and the Yucatan in the first place. To judge by the test scores, school performance should not have been a cause for concern.

Clearly there was a disconnect between the consequences of schooling as measured by standard psychological tests and by measures of academic achievement. It was the test that was taken as criterion, even when accompanied by school failure.

This line of reasoning about the distinctive role of language in school was reinforced by the study of young children’s talk when we took them to a supermarket and then back to the classroom. The major finding of that work can be seen as a demonstration of a strong disconnect between school and non-school-based knowledge acquisition processes. In school, the kind of speech acts one is allowed to use (and the circumstances for their use) are quite different from riding in a shopping cart while on an adventure. In the market, the children could initiate turns of talk and describe things of interest to them. Back in the classroom, they were placed in a position where they had to respond to teacher questions about events that had taken place elsewhere – that is, they had to learn what now might be referred to as “school discourse.” Talk in school was special. Considered as a context, not a place, classrooms took on special interest, along with clubs and other organized settings, as places valuable for studying learning and cognitive development as culturally mediated process.

Coming to Terms with Vygotsky

In light of the extent to which L.S. Vygotsky’s writings came to play a significant role in the work of LCHC over the decades, it may appear odd that thus far he has played little role in our narrative. In this section, we provide a summary of how our involvement in Vygotsky’s ideas about culture and development increased and diversified during LCHC’s residence at Rockefeller, a trend that continued at UCSD and will become important in later chapters.

The Reception of Vygotsky’s ideas during LCHC’s “Prehistory” period

In part, the relative absence of Vygotsky from our writing in the 1970s was a matter of simple ignorance. Despite the time that Cole had spent working with Alexander Luria, he had received no formal training as either a developmental psychologist nor as an historian of ideas; for a long time he did not understand Luria’s enthusiasm for Vygotsky’s work.

However, even as we began to learn more, we were put off by what we knew about Vygotsky’s ideas concerning primitive thought, as illustrated for us by the manner in which Luria interpreted his research results in Central Asia. In that work, Luria (1971, 1976) had famously concluded that the cultural-historical change from pastoralism to modern industrialized modes of life brought with it a generalized change in modes of thought from “concrete-functional” to “theoretical.” He assumed, invoking the theory that he had helped Vygotsky to create, that the cultural-historical changes wrought by modern life extended from perception through classification and reasoning to the personality as a whole. As cultures (presumably) progress, Luria proposed, so does the complexity and power of human psychological processes. This was just the sort of conclusion, based upon what appeared to be the same methodological practices, which we had been criticizing in our cross-cultural research. This tension can be seen in Cole’s introduction to the English translation to Luria’s 1976 book, Cognitive Development, Its Cultural and Social Foundations.

Moreover, at this time, Vygotsky was recruited as an ally by others engaged in cross-cultural work in a deficit-oriented manner that particularly concerned us. For example, Greenfield and Bruner (1966) interpreted their results on the failure of unschooled Senegalese youth and adults to solve Piagetian and other cognitive tasks in terms that explicitly evoked Vygotsky and Luria. They concluded their article with a strong statement about the cognitive consequences of schooling that seemed to fly in the face of our own research results. In short, in this view, some environments “push” cognitive growth better, earlier, and longer than others do.

As noted in Chapter 2, this cultural/cognitive deficit view carried over from cross-cultural research to the analogous issues in the U.S. all too uncritically. For example, Bereiter and Engelmann (1965), linked Vygotsky into their narrative of cultural deprivation arising from language deprivation as follows:

“As Luria and Vygotsky have explained, controlling one’s actions through one’s own words is a necessary step toward the mastery of dialectical reasoning, which in essence is controlling verbal behavior through “internal dialogue” by means of which one may solve a problem, working a step at a time…. and the deficiencies of culturally deprived children in this use are most striking” (p. 38).

It is no wonder that we approached Vygotsky reluctantly. He had found himself in what we considered “bad company!” But approach him we did.

Converging Sources of Vygotsky’s Influence on LCHC

Despite crosscutting inhibitory influences, a confluence of events began to remedy our inattention to Vygotsky, although it took several years for his ideas to become a central line of development for LCHC.

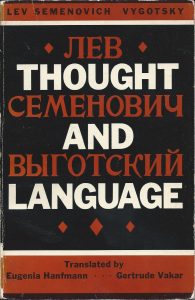

An early reconsideration of Vygotsky’s ideas was promoted by the invitation to write an article on culture difference and deficit with Jerome Bruner. Bruner had written the introduction to Vygotsky’s book, Thought and Language. He had also adopted a view of cultural differences and the cognitive impact of schooling that fit too comfortably with the kind of culture/cognitive deficit views that we were contesting.

The article reviewed the literature discussed in Chapter 2. After a lengthy period of negotiation, the article ended with what we believed was a more nuanced conclusion concerning the issue of differences and deficits as they manifested themselves in the American setting. The point of view adopted was that cultural deprivation represents a special case of cultural difference that arises when individuals are faced with demands to perform in a manner inconsistent with their past (cultural) experience. In the present social context of the U.S., the great power of the middle class has rendered differences into deficits because middle-class behavior is the yardstick of success.

Although this single discussion did not resolve all of the issues, it did begin a fruitful relationship that brought us into contact with one of the leading developmental theorists in the contemporary study of culture and thought. It also forced us to continue rethinking issues of development and learning that were central to Vygotsky’s approach (Cole & Griffin, 1980).

When Sylvia Scribner joined the nascent LCHC in 1970 she brought with her a strong background in Marxist theory and an unpublished paper on the cognitive consequences of literacy that drew heavily and approvingly on Vygotsky’s ideas (finally published in 1992). Her enthusiasm for conducting cross-cultural research to test Vygotsky’s ideas about the relation of writing to thought was a major reason for undertaking the Vai project.

At almost the same time, Luria began to prepare an intellectual autobiography with the understanding that Mike would be an editor. Since Luria constructed his autobiography largely as a playing out of ideas he attributed to Vygotsky, Mike was virtually forced to go back and reconstruct what made Vygotsky’s ideas so central to Luria’s career. To compound matters, Luria arranged for Mike to prepare two Vygotsky manuscripts for publication at Harvard University Press, where Luria’s American publisher, Arthur Rosenthal, had become the director. Knowing himself inadequate to the task, Mike asked Scribner for her advice. She brought Vera John Steiner, an admirer of Vygotsky’s work, into the process. The task proved to be far more than a matter of translating two monographs; it occupied several years and four editors in constant dialogue to arrive at a manuscript acceptable to Rosenthal and Luria. All of this work meant coming to grips in a serious way with Vygotsky and Luria’s ideas about development.

Further impetus for engagement with Vygotsky’s ideas was provided by the unexpected public response to Steven Toulmin’s glowing review of the resulting book, Mind in Society. Toulmin astounded us by dubbing Vygotsky the “Mozart of Psychology.” We found ourselves in the odd position of being treated as “Vygotsky experts” because we had produced this edited volume. We knew full well that we still poorly understood Vygotsky, but the attention focused on him by our colleagues meant that over time we had to work even harder at figuring out whether and how to reconcile his ideas about culture and development with our own.

Further impetus for engagement with Vygotsky’s ideas was provided by the unexpected public response to Steven Toulmin’s glowing review of the resulting book, Mind in Society. Toulmin astounded us by dubbing Vygotsky the “Mozart of Psychology.” We found ourselves in the odd position of being treated as “Vygotsky experts” because we had produced this edited volume. We knew full well that we still poorly understood Vygotsky, but the attention focused on him by our colleagues meant that over time we had to work even harder at figuring out whether and how to reconcile his ideas about culture and development with our own.

Beginning to Appropriate Cultural-Historical Theory: The Rockefeller Years

LCHC’s first serious introduction of Vygotsky’s theorizing into its publication repertoire appeared in a small textbook on culture and cognition published by Cole and Scribner in 1974, Culture and thought: A Psychological introduction. Referring to Vygotsky and Luria’s views on culture and cognitive development, the text suggested that human productive activity is the basis for human developmental transformation in “mental products”—a very different approach than could be found in writings on cross-cultural research at the time.

“[The socio-historical approach] represents an attempt to extend to the domain of psychology. [In] Marx’s thesis that man has no fixed human nature but continually makes himself and his consciousness through productive activity…The central idea…is that man’s nature evolves as man works to transform Nature. The sweep of this concept – that both subject and object, man and his product, arise from a unitary process of activity—can best be grasped by an understanding of what Marx meant by production. Marx used the term to refer not only to the making of material products but to mental products as well (law, religion, metaphysics, and so on); similarly, productive activity encompasses not only manual but mental labor – labor in the broadest sense” (p. 31).

Cole and Scribner (1974) emphasized (as did Vygotsky) that the complex, dynamic, and interrelated nature of all phenomena makes it impossible to simply extrapolate principles from Marx and apply them to the scientific question at issue. However, at the end of their text, after reviewing extant cross-cultural data for a wide variety of classical psychological processes, Cole and Scribner fastened on the concept of functional system as a potentially useful way to conduct cross-cultural research in the future.

In the context of the study of brain localization, Vygotsky and Luria had argued for the view that higher [culturally mediated] psychological functions are complex, organized functional systems, which they conceived of as organizations of cognitive processes, themselves flexible and variable, that are directed toward a specific end. The key change in thinking that was signaled in the Cole and Scribner text on cross-cultural research was a shift in focus away from thinking of psychological processes as discrete and discretely measurable elementary psychological functions to focus instead on human functional systems in which the socio-culturally organized settings and cultural practices play an integral role.

Here we see the first signs of a line of theorizing applicable to the Lab’s early cross-cultural research that also held promise for providing a positive account of how universal “basic” psychological processes (“elementary psychological functions”) could be aggregated within “situations” (culturally specific functional systems of activity) to enable human thought and action. These ideas pushed LCHC researchers toward a way of thinking of schooling as an historically evolving system of activities that were distinct from but related to the “everyday lives” of people in different times, spaces, and places..

The gradually increasing influence of cultural-historical psychology appears most concretely in two of the major projects that were being completed at the time that LCHC left Rockefeller University. The first was Scribner and Cole’s own engagement with the notion of the psychological consequences of Vai literacy discussed in Chapter 3. The second was in our work on ecological validity described in Chapter 4.

With respect to the Vai project, we began with the notion that it might be possible to verify Vygotsky’s claims about the special properties of print-mediated action. Our major focus was on examining the interconnections between written language and the activities it mediates. In the Vai research on the practices of schooling, “literacy as embodied in practice” rather than “literacy as a set of isolatable cognitive skills,” turned out to be the most useful way to make sense of the results obtained. Characteristic of our prior cross-cultural research, the conclusions drawn about the influence of writing on cognitive development among the Vai were critical as well as laudatory about Vygotsky’s ideas, in this case, his ideas about the consequences of literacy.

When we took on the task of writing about the MCS Ecological Validity Project, we began to see a quite different significance and usefulness in Vygotsky’s ideas. Broadly speaking, he was helpful in highlighting unresolved problems with the experimental psychology of learning and the need to develop an alternative psychology of learning at the person-environment interface (understood as the local sociocultural context). While the monograph Ecological Niche-Picking (1982) devoted only a few paragraphs to Vygotsky, they proved prescient:

“What we find especially attractive about Vygotsky’s theory is the way in which he incorporates features of social/environmental forces directly into his specifications of cognitive processes, both as their sources and part of their content. But what Vygotsky did not prepare us for is that children and adults would spend so much of their time arranging their environments so that they did not need to engage in cognitive activity without environmental support. While internalization of activities originating in the environment may be a proper characterization of what people become more able to do as they grow from infancy to adulthood, and what they do when constrained sufficiently, non-internalized thinking, in which cognition resides in the environment as much as in the individual, is a pervasive phenomenon.”

We agreed with the primacy of the interpersonal in this formulation but in our observations of children in various settings—schools, tests, and clubs—we had been constantly confronted with how little we need to postulate internalization in order to describe the children’s behavior. We expressed our concerns in this way:

“To Vygotsky’s statement that “All higher functions originate as actual relations between human individuals” (1978, p. 57), we would add that under many different circumstances of everyday life, that is where they remain. People learn about themselves and about each other by the work they do constructing environments for acting on the world. And this is how we must come to know them as well.”

Vygotsky pointed us in the direction of creating an account of human thought processes that focused on how the “inner” and the “outer” are primally interwoven through culturally mediated and socially organized interpersonal interaction. In this respect, we were part of a broader intellectual movement seeking to overcome the intellectual-philosophical dualistic divide between the “inner” and “outer” in human psychological functioning. Former LCHC participants have continued to be inspired by his writings and to expand upon his methodological insights and empirical findings, not as abstract psychological concepts, but as applicable to current socio-cultural-political life conditions.

Chapter Five Compositors: Michael Cole, Bud Mehan

Back to Chapter Four

Forward to Section Three Introduction