In order to understand the mixture of academic and social issues that came together in the formation of LCHC, we begin by elaborating in a little more detail the socio-historical circumstances within which the lab emerged. We then summarize the basic program of cross-cultural research that provided the initial set of academic issues motivating the formation of LCHC as a research laboratory.

The Social-Historical Context

During the 1960s, several social trends converged to focus scholarly and social attention on the relationship between cultural experience and intellectual development. The first trend was a global focus on spreading and intensifying formal education as a mode of economic and social development, a necessary accompaniment to the process of de-colonization. The second trend was the intense international conflict known as the Cold War in which the Soviet Union and its allies were pitted against the U.S. and its allies for global influence. In an era of intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear weaponry, winning this conflict was seen as a matter of national survival and of preserving “our way of life.”

The International Context

The launch of Sputnik in 1957 challenged the U.S. in profound ways. In particular, the existing sense of technological superiority was shattered.

In the aftermath of Sputnik, the U.S. initiated a wide variety of educational reforms focused on science and technology (what are now referred to as the STEM disciplines) in an effort to “catch up” in the technological race that it previously thought it was leading.

The importance of elevating the educational capacities of “Third World” nations represented a point of convergence between domestic desires to improve the educational achievements of the U.S. population and international efforts to promote economic development in “under-developed” nations. Comprised largely of former European colonies, the “Third World” became an important arena of Cold War competition as each side sought to extend its influence through programs of foreign aid that provided support for building formal educational infrastructures.

The international programs created to fulfill these educational goals shared a common understanding of their task, which focused on their role as a coordinating mechanism of otherwise contending nations. These goals were expressed in the planning documents of The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). International academics and policy makers agreed that low levels of economic, political, and cultural development were associated with immature thinking that would ultimately block the economic changes that the United Nations (UN) architects of the future were imagining for the world.

This premise, which linked socio-cultural-economic development with intellectual development, was expressed clearly in the statements of UNESCO’s founders when they spoke of the need for a “wide diffusion of culture” to the Third World. This “giving them culture” orientation comes through clearly when, in the same document, UNESCO wrote that “ignorance is not an isolated fact, but one aspect of general backwardness which has many features, like paucity of production, insignificant exports, poor transport and communications, deficient capital and income, [etc.]” (UNESCO, 1951, p. 4).

Much in the spirit of UNESCO’s view, development economist Daniel Lerner similarly argued that a key attribute of modern thinking is the ability to take another person’s perspective and empathize with their point of view. Lerner was quite specific about the relationship between psychological modernity and modern economic activity. From his perspective, the ability to take another’s point of view, “is an indispensable skill for moving people out traditional settings…Our interest is to clarify the process whereby the high empathizer tends to become also the cash customer, the radio listener, the voter” (Lerner, 1958, p. 50).

Taken together, these experts supported a belief that Third World peoples lacked critical forms of intellectual ability owing to deficiencies in their environment. As a consequence, so went this logic, they could not enter into modern economic and political relations. The solution, then, was to spread formal, industrial-style education into the Third World along with our “goods and services.

The Domestic Context

In parallel with the international situation, social processes within the U.S. made education a focal point for discussions about race, ethnicity, and social inequality. The 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision initiated the process of desegregating American schools, although it did not produce any visible change in the relative achievement of African American children. This situation, given the name of “the achievement gap”, has remained a central issue in debates about American educational policies today.

In 1964, the U.S. initiated a “war on poverty”. One of the nation’s major weapons was  Project Head Start, a massive program of early childhood education and health care. Based upon a variety of reputable data on child development, it was believed that early childhood intervention would show successive reduction of the achievement gap. In addition, it was argued that children would progress more seamlessly through the grades given a proper head start. However, this hoped-for solution did not appear to work.

Project Head Start, a massive program of early childhood education and health care. Based upon a variety of reputable data on child development, it was believed that early childhood intervention would show successive reduction of the achievement gap. In addition, it was argued that children would progress more seamlessly through the grades given a proper head start. However, this hoped-for solution did not appear to work.

The Intellectual Context

In light of the broad interest in using formal education as an engine of human development, a number of governmental and philanthropic organizations became actively interested in research that would help plan how to organize for mass education. During the late 1950s and continuing throughout the following decade, a number of social science research programs were mounted to provide empirical information about cultural variations in psychological development, including how such variation should influence educational practices. These programs of research sprang from different theoretical sources including psychology, and a broad range of developmentally relevant disciplines gathered under the rubric of developmental science.

Jean Piaget: Cross-Cultural Evaluation

By far the largest of the projects to come directly out of this movement was motivated by broad interest in Jean Piaget’s theories. Early in his career, Piaget (1928) argued for the existence of important developmental differences in cognitive development associated with cultural variations. Citing the work of Lucien Levy-Bruhl (1910) and Émile Durkheim (1912), Piaget distinguished between two kinds of societies. He suggested that each kind of society had its own mode of thought, which Lévy-Bruhl characterized as “primitive” and “civilized” and which today might be distinguished as “traditional” and “modern.”

Piaget (1966) wrote an influential article in which he called for cross-cultural evaluation of his ideas and summarized then-extant research to conclude that education could be considered one of four basic factors associated with development. This represented something of a concession for Piaget because in some of his writings he had argued that formal education fails to promote development because schools are institutions where accommodation overpowers assimilation, resulting in inert knowledge. In 1966, however, he suggested that true developmental differences could be created via education insofar as educational experience could provide children more overall experience related to discovering the nature of the world.

In general, the spate of Piagetian research begun in the 1960s found a good deal more variability among societies than Piaget had anticipated. In some cases, little or no difference in achieving Piagetian developmental milestones was observed. In other cases, however, researchers reported that children from traditional, non-industrialized societies lag one or more years in the age at which they achieve the stage of concrete operations as compared to children in Western, industrialized societies. There were also studies in which young teenagers and even adults failed to demonstrate understanding of the principles underlying conservation in the Piagetian tasks. This sort of finding led to the widely cited conclusion that perhaps some societies create experiences for their children (e.g. formal education) that speed up cognitive development and push it to a higher level than others.

See LCHC (1983) for an extensive review of this literature and the other programs mentioned below. See also Cole’s (1988) article, Cross-Cultural Research in the Sociohistorical Tradition.

Cognitive Style Approach

Another prominent program of research began with the idea that cultures are “designs for living” (Kluckhon, 1952). This perspective suggests that one should understand cultural influences on development in terms of cognitive styles –that is, the pervasive tendencies to think about the world in ways that fit into the particular, unique pattern of a given culture.

Several procedures were devised to measure different manifestations of the cognitive style in different domains of psychological functioning: problem solving, perception, regulation of interpersonal interactions, and so on. For example, the extent to which people depend upon their bodies versus their surroundings to judge what is upright might be compared with their ability to extract perceptual figures embedded in a complex visual field based on the assumption that there is a cognitive style associated with “field independence” or its antimony, “field dependence.” These psychological proclivities were then related to environmental factors that might act as an ensemble to create, for example, field independence. At present, this line of work has gained prominence as the study of individualism and collectivism, and it represents perhaps the most active line of current cross-cultural research.

In the 1960s, cognitive style research was part of a broad attempt to demonstrate that different group-wide styles of thought and feeling can arise in quite different geographical environments depending upon key features of how the local culture has formed as a medium for dealing with its environment. In this research, socialization practices and features of the environment jointly entered into such theories. Schooling was not a central concern to cognitive style research because it was seen as part of a more encompassing socio-cultural environment.

Educational Development Corporation

By contrast with either the Piagetian or Cognitive Style approaches, schooling was a central concern in the approach to culture and development that began to develop in Liberia in the mid-1960s. LCHC’s formation began as a small part of an international educational research initiative sponsored by the Educational Development Corporation (EDC), an influential education research organization located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the time, EDC served as an organizational base for number of senior scientists in leading American institutions who had become concerned about the need to organize for a greatly expanded labor pool of scientifically and technically educated people to sustain American economic and political prosperity.

This group pioneered a number of the innovative, activity-centered curricula in the hard sciences and biology. One of its members, Jerome Bruner, was leading the controversial curriculum effort, Man: A Course of Study (1965), which adopted a view of culture as the historically constructed ways in which people deal collectively with their environment. The curriculum sought to illustrate this point and to serve as a provocation to think about how cultural variation, understood in this way, could be made consequential for organizing successful education.

New Mathematics

One of the educational reforms to come out of this discussion was a new way of introducing children to mathematics in elementary school, which came be to called “The New Mathematics.” As part of research on the implementation of this new curriculum, the idea arose to implement the new approach to newly emerging school systems in Africa.

Initial observations were made in the remote town of Gbansu. At the time, the town was most easily reached by light aircraft.

At a meeting of experienced mathematics teachers working in Africa designed to promote uptake of the new curriculum, one person was quite clear about his doubts concerning the utility of the new approach to the problems of African mathematics education. That man was John Gay, one time a graduate student in mathematics at Princeton University. Gay left Princeton and opted for the ministry, ending up in Liberia where he had been teaching mathematics at Cuttington College (Now Cuttington University), established by the Episcopal Church of the United States.

Gay’s arguments drew enough support from the leadership of EDC to support an initial attempt to dig more deeply into the difficulties that children were experiencing in adopting the new curriculum, Gay and Michael Cole were allowed to conduct some initial studies to ferret out the sources of poor performance based on apparent conceptual misunderstandings that Gay had identified. This work (Gay and Cole, 1967; Parts One, Two, and Three) attracted sufficient scholarly attention to enable them to obtain a rather substantial grant to follow up on their initial findings.

Gay’s arguments drew enough support from the leadership of EDC to support an initial attempt to dig more deeply into the difficulties that children were experiencing in adopting the new curriculum, Gay and Michael Cole were allowed to conduct some initial studies to ferret out the sources of poor performance based on apparent conceptual misunderstandings that Gay had identified. This work (Gay and Cole, 1967; Parts One, Two, and Three) attracted sufficient scholarly attention to enable them to obtain a rather substantial grant to follow up on their initial findings.

For this second round of work, they recruited the help of Joe Glick, a developmental psychologist with an interest in the issue of cultural contributions to development. Together with Donald Sharp, a former undergraduate assistant of Cole and Glick’s at Yale, and a host of local Liberian college students, this team set out to see if they could put together a more adequate account of cultural differences in cognitive development, including how these differences were related to formal schooling.

Each project sparked a re-examination of how scholars warrant their conclusions about the role of culture in human development, the influence of institutionalized formal education on cognitive development, and the nature of psychological research into these issues. Each project also functioned as steps toward the formation of LCHC.

Refocusing the Discussion: New Mathematics and an Old Culture

At the time when Cole and Gay began their research, the idea that local tribal children suffered from specific forms of cultural deprivation was ubiquitous among the educationalists working in Liberia. As Cole (1978) summarized the situation:

“The list of things that the tribal children could not do, or did badly, was very long indeed. They could not tell the difference between a triangle and a circle because they experienced severe perceptual problems. This made the tribal child’s task almost hopeless when it came to dealing with something like a child’s jigsaw puzzle, explaining why ‘Africans can’t do puzzles.’ I heard a lot about the fact that ‘Africans don’t know how to classify’ and, of course, the well-known proclivity of African schoolchildren to learn by rote came in for a lot of discussion and help” (p. 616).

Although such conclusions drew upon a long history of 19th and 20th century scholarship, not to mention UNESCO documents such as those cited above, the people who made them were basing their ideas entirely upon fantasy. They had the evidence of their own experience. Children who played around the living quarters at Cuttington College experienced what seemed like extraordinary difficulty doing jigsaw puzzles. Students attending the college appeared to experience extraordinary difficulty mastering the mathematics curriculum. Various forms of extreme rote learning were observed in elementary school mathematics classrooms. Yet the broad conclusions about cultural causality based upon such observations seemed overdrawn, especially since they all took place on the educator’s home turf, culturally speaking. And the solutions offered (“flood the country with erector sets”) were not particularly helpful.

Rather than jump to conclusions about Liberian child and adult intellectual disabilities, Gay and Cole approached this issue with the added common sense assumption that, although Kpelle children lacked particular kinds of experiences routinely encountered by children in the U.S., they were by no means lacking in experience. Gay and Cole (1967) explicitly began with the assumption that it was important to know more about “indigenous mathematics” in order to build “effective bridges” to the new mathematics curricula they were trying to introduce. This core assumption led them into an exploration of the way that numbers, geometrical forms, and logical operations are expressed in the Kpelle language.

An additional common sense assumption of this early work was that people would be skilled at tasks they had to regularly engage in as a part of their everyday activities (see slideshow on right). This statement may seem patently obvious or trivial, but its consequences are neither. It led directly to the conclusion that if they wanted to understand why Kpelle children have difficulty with the kinds of problem solving tasks American academics consider relevant to mathematics, they needed to consider the circumstances in which Kpelle people encounter something recognizable to us as mathematics. That is, they needed to study people’s everyday activities that involved measuring, estimating, counting, calculating, and the like as the precondition for diagnosing indigenous mathematical understanding in relation to schooling (see slideshow on house building below).

The fact that we were able to gain scholarly attention to the challenges posed by these two assumptions appears, in retrospect, to be the cardinal contributions of this work. It was not sophisticated by any stretch of the imagination, but it caused people to stop and think.

Estimating Rice: Cultural Tools and Associated Cognitive Skills

One particular task that sparked widespread interest in the academic community was estimating amounts of rice. The Kpelle have traditionally been upland rice farmers who sell surplus rice as a way to supplement their very low incomes. Upland rice farming is a marginal agricultural enterprise and most villages experienced a “hungry time” in the two months between when their supply of food from the previous year had been used and when the new crop would be harvested.

As might be expected from the centrality of this single crop to their survival, the Kpelle have a rich vocabulary for talking about rice. Of particular interest to Gay and Cole were the ways the Kpelle talked about amounts of rice. Gay and Cole had been told rather often that the Kpelle could not measure, and they wanted to see what would happen if the Kpelle were asked to measure in a domain of deep importance to them.

Simple ethnographic investigation revealed that the local standard minimal measure of rice was a kopi, a U.S. tall tin can that holds one dry pint. Rice was also stored in boke (buckets), tins (pint size tin cans), and boros (bags). The kopi acted as a common unit of measure. It was said that there were 24 kopi to a bucket and 44 to a tin, and that two buckets were equivalent to one tin. People claimed that there were just short of 100 kopi to a boro, which contained about two tins. The relationships between cups, buckets, tins, and bags are not exact by our standards. But they are close, and they reflect the use of a common metric, the cup.

Gay and Cole also learned that the transactions of buying and selling rice by the cup were slightly different in a crucial way. When a local trader bought rice, he used a kopi with the bottom pounded out increasing the volume in the container; when he sold rice, he used a kopi with a flat bottom. This small margin of difference made a big difference to people who refer to two months of the year as “hungry time.”

Gay and Cole decided to conduct an experiment on people’s ability to estimate amounts of rice in a bowl using the kopi, the local measuring tool that holds a dry pint in U.S. measurement standards. Using these materials, they conducted a “backwards” cross-cultural experiment modeled on Kpelle practices using Kpelle bowls and cups. The participants were working-class Americans and Liberian farmers. Each person was presented with four mixing bowls of the same size and asked to estimate the number of cups of rice in each. At the same time, they were shown the tin to be used as the unit of measurement. The bowls contained 1½ , 3, 4½ , and 6 kopi of rice. Kpelle adults were extremely accurate at this task, averaging only one or two percent error. American adults, on the other hand, overestimated the 1½-can amount by 30% and the 6-can amount by more than 100%.

These results supported Gay and Cole’s basic assumptions that people would develop cultural tools and associated cognitive skills in the domains of life where such tools and skills were of central importance, as rice was to Kpelle life. Whatever the cultural differences with respect to the domain of mathematics, a total lack of measurement concepts and skills did not appear to be one of them.

A conspicuous feature of the rice estimation task was that Gay and Cole were able to create an experiment that not only incorporated local knowledge concerning content (e.g., the Kpelle system of units for amounts of rice) but also local procedures under which such estimates would be relevant. At markets, one often encountered women selling rice from large bowels containing various amounts. Consequently, this task provided Kpelle people with both relevant content and relevant procedures.

Other Psycho-Educational Tasks

Not all of the methods Gay and Cole used achieved this kind of “groundedness.” Uncertain of the scope of the question they were being asked to address about the causes of children’s difficulties with school-based mathematics instruction, they actually studied a spectrum of psycho-educational tasks, some imported directly from U.S. psycho-educational practices and others made up on the spot. The tasks included simple classification of objects, a basic, 5 piece, jigsaw puzzle, and a vocabulary test of the sort often found in IQ tests. When confronted with these sorts of tasks, attending school appeared to improve performance.

Overall, the data suggested that no generalized lack of mathematical, perceptual, or problem solving abilities stood in the way of mathematics education. When the materials and procedures used in assessment tasks were designed to match closely valued local practices, lack of ability could be replaced by apparent special ability. At the same time, schooling did appear to influence performance in tasks that were routinely used to measure cognitive development.

These results seemed intriguing and worthy of more systematic attention, particularly since many were based upon untested procedures that had been cobbled together in the field. Gay and Cole clearly had conducted far too little ethnographic work to provide more than a hint of what might be learned beyond the domain of mathematics. Fortunately, the attention attracted by this initial foray into cross-cultural research was sufficient to obtain the funding needed to pursue the agenda opened up by the “New Mathematics” project. Equally important, Gay and Cole obtained the collaboration of Joe Glick, who was trained in classical developmental psychology, adding a central area of expertise that was lacking.

Struggling with Context: Ethnographic Psychology & Experimental Anthropology

In the years that passed between the initiation of the New Mathematics Project and the completion of what we will call the Cultural Context Project, the U.S. underwent a fundamental shift in its foreign and domestic policies that brought the civil rights movement into convergence with opposition to the war in Vietnam. Martin Luther King’s dreamers of the early 1960s had lost their great inspirer, and his death was just one of many manifestations of the violence that wracked the U.S.

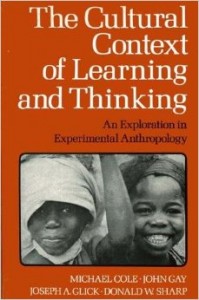

Like a great many academics, the authors of The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking (Cole, Gay, Glick, & Sharp, 1971), a monograph that resulted from The Cultural Context Project, were caught up in the conflicts of the time, which re-framed their work in a significant way. For reasons we return to in the next chapter, this cross-cultural work entered into debates at the national level that were focused on the value of the massive head start program. It also entered into debates at the academic level, fostered by Arthur Jensen’s publications attributing difference in school success to genetically determined factors associated with race.

Like a great many academics, the authors of The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking (Cole, Gay, Glick, & Sharp, 1971), a monograph that resulted from The Cultural Context Project, were caught up in the conflicts of the time, which re-framed their work in a significant way. For reasons we return to in the next chapter, this cross-cultural work entered into debates at the national level that were focused on the value of the massive head start program. It also entered into debates at the academic level, fostered by Arthur Jensen’s publications attributing difference in school success to genetically determined factors associated with race.

This framing of the work is important to consider because it explains why research on cultural differences between people living in rural Liberia and suburban California seemed relevant for the American scene. When imported from Liberia to the U.S., results that showed a great variety in the way rural Liberian farmers solved intellectual problems disrupted the idea that any sort of general deficit afflicted these people. It also struck at the idea that the apparatus of experimental psychology, as then practiced, could legitimately claim to reach conclusions about learning ability.

This line of thinking came to be associated with what is referred to as a “difference interpretation” of cognitive development and cultural milieu. Within the American context, scholars who supported the “cultural deficit” thesis, which assumed that ethnic minority/poor children grew up in environments that were deficient, contested this “difference interpretation” of cognitive development. Both points of view exist to the current day, even as increased knowledge about biological-cultural interconnections has made the debates more complex. We consider the current situation in later chapters, but we pause here long enough to offer a sense of the additional kinds of evidence that several years of research using a broad variety of methods added to conversation.

Putting Together a More Adequate Methodology

A general message that we took away from the New Mathematics project, as expounded in The Cultural Context of Learning and Thinking, is that people will be best at doing the tasks that they perform on a regular basis, the things that are most relevant to them (p. xi). In an ideal world, this meant that the research team would develop a comprehensive “cognitive ethnography” of Kpelle society and use it as a matrix against which to conduct systematic studies of culture, schooling, and cognitive development. In reality, however, they could not wait for such a complex ethnography to be completed because they needed to deliver results within three years – ethnography, schooling, testing, the whole ball of wax.

The approach that emerged to meet this impossible set of demands began, so to speak, from both sides at once. On the one hand, the research team had access to ethnographic information and used it to assess the kinds of thinking that people engaged in. But at the same time, they also had experimental procedures that seemed to be of a simple sort, easily communicated, that could help better understand how age and education were implicated in the levels and modes of performance that people engaged in.

This age/education nexus was of keen interest in Euro-American psychology at the time because there appeared to be broad agreement that a marked change occurs in cognitive processes between 5 and 7 years of age (for more, see the 5-7 shift). This is the age period, for example, that marks the advent of concrete operational thinking as expounded in Piaget’s work. It was also the object of attention of American learning theorists, who linked cognitive transformations to marked changes in opportunities for learning that children began to experience during this age period, whether in school or outside of it (see White, 1965).

With respect to disentangling the factors involved in the 5-7 shift, Liberia was attractive because schooling was still primarily restricted geographically in relation to towns built along the roads constructed by foreign concessions for the extraction of natural resources. In most places, schooling had only arrived recently. Because of this, many people (of all ages) had not experienced formal education. This set of historical circumstances made it possible, at least in theory, to separate the influence of a child’s chronological age from the kinds of changes in experience undergone in connection with schooling and indigenous activities.

Examples of “Ethnographic Psychology / Experimental Anthropology”

From the large set of studies conducted over a four year period, we have select three examples of strategies we used to combine ethnographic investigation of Kpelle language and culture with the analytic apparatus of experimental psychology, which purported to provide evidence about the mechanisms of learning and problem solving.

(1) Learning about Leaves

In a poignant description of her early attempts to learn Igbo during her fieldwork in Nigeria, Elenore Smith Bowen (Laura Bohannan), recounts her great difficulty in learning the names of the different leaves that people used in their everyday life (Return to Laughter, 1954). Beryl Belman, then a graduate student and our project’s “cognitive-ethnographer”, had the same problem when he sought to study local medicines. Leaves are central to local medical practice, and Beryl could not distinguish them, practice though he might.

We used this observation to create a learning experiment in which the task was to classify leaves. The leaves were of two kinds: those taken from local vines and those taken from local trees. In the most straightforward case, people were told that they would be shown a set of leaves, one at a time, and they were to divide them into vine and tree leaves. Under these conditions, all of the uneducated Kpelle adults who were tested made the correct classification either right at the start, or after one pass through the set of leaves. No problem. After 10 cycles through the leaves, American Peace Corp volunteers could not learn to classify twelve leaves despite being identified as leaf or vine after each cycle.

As an indicator of how important local categorizations of leaves would be to those who learned the categories, we included a condition where the two kinds of leaves were assigned to categories at random. In this case, the Kpelle subjects (psychologese for the people who are asked to engage the task) as well as the Americans experienced great difficulty, although the Kpelle gave some evidence of learning while the Americans did not.

The results from the first two “leaves experiments” are more or less in line with what we might expect from the ethnographic examples. However, a third experimental condition greatly complicated matters. In this condition, the two categories of leaves were again to be sorted into categories of vine versus tree leaves. However, in this case, the experimenter did not designate the leaves by referring to them as vine or tree leaves. Instead, people were told that half the leaves belonged to a man name Togba and the other half to a man named Sumo. In this case, the Kpelle participants failed to learn to sort the leaves.

This left us with a puzzle. Why, if we know that local people can sort those leaves when they are asked to do so in a straightforward manner, do they fail to do so when the categories are signaled not by their habitual labels, but by a fictitious “person” said to possess them?

(2) Categorical Organization and Remembering

One of the most extensive series of studies carried out as a part of the Cultural Context Project concerned the way in which people learn and organize sets of objects or lists of words. The specific procedure is referred to as “free recall” because the items to be remembered, although presented in sequential order, can be remembered in any order the person chooses. Interest then is focused on the order in which the words are remembered and how many are remembered. In particular, if the set of items is made up of clearly recognizable and familiar categories, will people remember them in the order presented or “cluster” them by categories? After a good deal of preliminary work to establish the items and categories to be used, the studies were carried out in ways that contrasted age and schooling to the extent possible.

In the most straightforward replication of procedures used in the U.S., people were told to remember a list of common nouns consisting of familiar objects: clothing, food, utensils, and tools. They were read the list and asked to recall the items in any order. This procedure was repeated five times with the order of the items scrambled each time.

These initial “list reading” studies indicated that traditional Kpelle farmers recalled relatively few items and failed to learn many new items with repeated presentations of the list. The sequence in which words were recalled conformed to no recognizable pattern of organization. This generalization held even though the experiment was modified to include monetary incentives, different kinds of words, concrete objects, and a variety of other stratagems aimed at producing good recall.

By contrast, Kpelle who attended high school remembered well, learned rapidly, and manifested a high degree of conceptual organization in the way they recalled the lists. One implication of this work was that developmental changes in free recall and clustering observed in the U.S. might well be measuring something about the influence of years of formal schooling, not age. But as interesting as that possibility might be, it does not explain why people who had not attended school appeared to be so inept at remembering what were, corroborating studies showed, familiar items and categories to the people involved.

A final study in this series further complicated matters. Drawing upon the Kpelle practice of storytelling and riddling, we created a story that mimicked a local genre but contained the same to-be-remembered categories as in the prior research. When integrated as part of the story, the order in which items were recalled conformed to the categories into which they had been grouped in the story.

Again, we have a case where, when a deliberately designed psychological task is presented, Kpelle rice farming people appear to experience extraordinary (to us) difficulties. However, performance markedly improved when the categorical/conceptual relations within the materials they are asked to learn are made clear, either through explicit linguistic designation or mediated by a familiar cultural practice (in this case, using a local story telling practice).

(3) Making Simple Inferences

Our last example illustrates that interpretations of cognitive development based on research in the U.S. fundamentally change when following the procedure of iteratively modifying pre-scripted cognitive tasks to tease out the factors associated with low or high performance. The task in this case was to learn to make a simple inference by piecing together three easily learned associations and then inferring what combination of two of those associations will produce a reward (candy for children, money for adults).

We selected this task for two related reasons. First, it had been used in research with American children and appeared to show the kind of “5-7 shift” in modes of responding associated with stage theories of cognitive development. Because of this, it seemed pertinent to our goal of separating age and schooling in the development of cognitive processes. Second, it was part of a suite of tasks devised to test the idea that changes in performance are symptomatic of a general intellectual change in which language contributes to thought processes in a new way (White, 1965; Vygotsky, 1962). Since features of language use in classrooms were then, and remain, prominent in psychological debates about the effects of schooling, the experimental procedure seemed to offer a promising way to address these concerns.

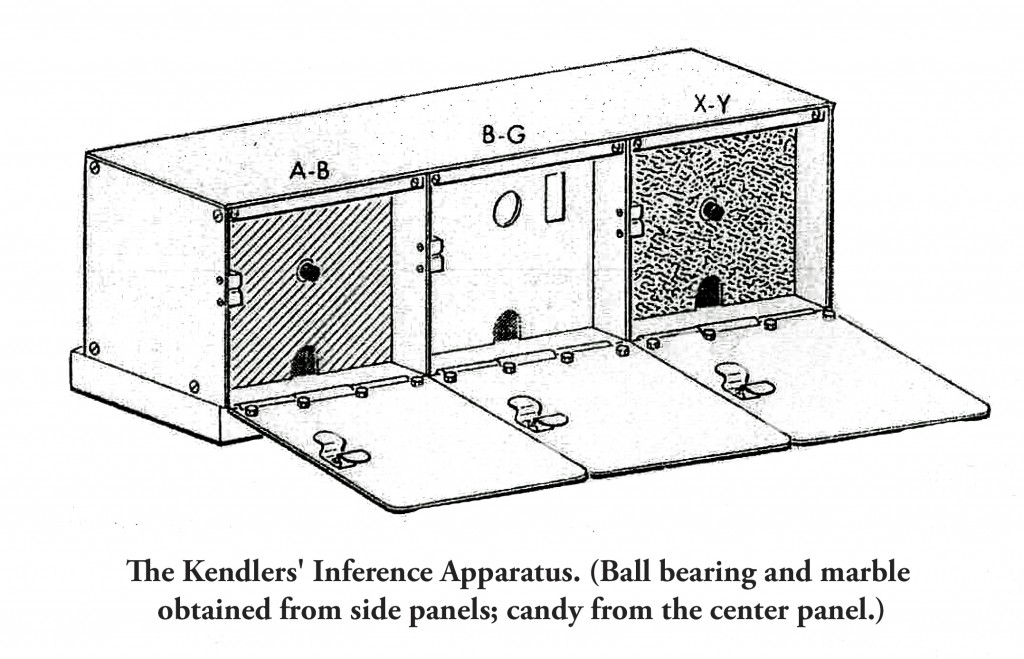

We began this set of studies using the device that Tracy and Howard Kendler (1962) used in their own research (see Figure 1, below). The apparatus was made of tin and when used in the U.S., it operated electronically. Somewhat fearsome, we thought. We learned to operate the apparatus by hand, but the idea was to stay as close to a real replication with the original apparatus as possible.

Figure 1: Inference Box

Subjects were taught that pushing the button on the left-hand panel would yield a marble, which drops into a tray below. Next, they were taught that pushing the button on the right-hand panel would yield a ball bearing. Then, with the two side panels closed, they were taught that putting (say) the ball bearing in a hole in the center would yield a piece of candy. Once all of this had been learned, all three panels were opened at once, and the subjects were instructed to obtain the candy, which they could keep and eat.

The question was: would they choose to obtain the marble or ball-bearing to get the candy, a task they have not been explicitly taught?

Described in this manner, the task facing the subjects was absolutely trivial. However, implemented in real life, whether in Santa Barbara or rural Liberia, the task proved challenging for some of the groups of people studied. In the U.S., the Kendlers found that even at third grade (roughly 8 years of age) only half the children in their studies would immediately start pushing the correct button and then put the correct object into the hole to get the candy. Older groups of children instantly solved the problem.

When this same task was presented to groups of traditional Kpelle (both children and young adults), performance was very unimpressive. Only 15% of the young adults who had never attended school spontaneously solved the problem. School attendance was associated with higher performance, but even 10-14 year-old school children spontaneously solved the problem less than half of the time. Overall, people seemed somewhat confused and even fearful of the apparatus.

As could be expected, we began by creating a logically equivalent task, but using locally familiar materials ––two distinctive match boxes, each with a distinctively colored key in it. One of the keys, when dropped in a wooden box, produced a suitable reward. These changes produced the expected results. When the local materials were used, performance shot up, even for the younger children who had not been to school.

Seeking to pinpoint the part of the process that seemed to be disrupted by the unfamiliar apparatus, we conducted another series of studies, this time including American children of different ages. The details of this work involved arrangements where keys from matchboxes were dropped into the fearsome metal box and other maneuvers that fit the research conventions of the time. The long and the short of the outcome was that if the first part of the task was carried out with familiar materials such as match boxes and keys, even if the keys had then to be dropped into the fearsome metal box to get a reward, the problem was solved with relative ease. But, if the problem began with the metal box, performance was depressed to the level observed with that initial, “standard” apparatus alone.

A bonus in this work was that by bringing our new research questions about the familiarity of the apparatus into the American developmental arena, a genuinely new finding was obtained. When presented with the match box/keys/drop the key in the box version of the task, American third graders now solved the problem (Cole, Gay, Glick & Sharp, 1971).

An Initial Summing up of the Evidence, circa 1971

When it came time to summarize our results, we were hard pressed to formulate an overall explanation of the results. We had succeeded in several cases to combine ethnographic evidence about common local cultural practices with experimental- psychological analysis. In many cases, it proved possible to demonstrate that local people were capable of engaging in various cognitive activities just fine so long as the tasks were, in various senses, familiar (Later, Margaret Donaldson would coin the term tasks that “make human sense” in her book, Children’s Minds).

In other cases, it appeared that the kinds of tasks drawn from schooling activities posed difficult challenges to people who had not encountered school, even when we sought all the means we could think of to make the task comprehensible and doable. With so many missing parts to the puzzle, we confined ourselves to concluding:

“Cultural differences in cognition reside more in the situations to which particular cognitive processes are applied than in the existence of a process in one cultural group and its absence in another” (p. 233).

Note how neatly hedged this summary is. We did not deny the possibility of specific cognitive differences between cultural groups arising from differences in specifiable experiences. After all, we were continuing to argue that the effects of culture on development should be sought through analysis of the kinds of activities that people engage with and are expected to be competent at accomplishing. Schooling is an everyday activity in the lives of children where it is present and they attend, even for a few years. But schooling, on the basis of our research, did not make a general cognitive difference. Rather, it made a difference with respect to those intellectual processes that schooling practices engage.

All of this may seem sufficiently banal to make it a curiosity, but what we claimed about schooling we thought to be a general principle so long as the research was careful to include both the activities of schooling and those of indigenous tasks and knowledges. This proviso meant that, using the scientific means at our disposal, we could not legitimately make generalizations about culture and memory ability or about culture and the development of categorization. We could, however, make warrantable inferences about the specific kinds of activities we studied. The origins of a “cognitive ability” by this view are tightly connected to particular activities or contexts of use.

Taken as a whole, this work cast doubts not only about generalizations concerning culture and cognitive development but also about the conclusions concerning processes of cognitive development that dominated the professional literature in the industrialized world. Conclusions about age-related performance differences in the U.S. appeared to be badly compromised by hidden biases that crept into a study’s design. These doubts, transposed into the arena of American academia in 1971, provided the initial social impetus to create LCHC.

Chapter One Compositors: Michael Cole, John Gay, Joe Glick

Chapter One References and Additional Resources

Back to Section One Introduction

Forward to Chapter Two