During the period when large, collective projects of the sort described in Chapters 12-14 were being carried out, a number of smaller, independent projects were carried out by Lab members for their Ph.D. theses and explored themes that ranged across the intellectual issues that had concerned LCHC since its inception.

As life would have it, all of the people engaged in these projects, although they have written up their work for various venues, are too occupied with problems of transition and security, and have only had time to prepare rough draft accounts of their work. So, we present these lines of work here in abbreviated form until such a time as the authors expand their presentations. Each individual draft account is accompanied by links to original documents or sources of publication so that readers can follow each of these threads backward to their sources or forward into the intellectual landscape into which they are entering.

The Sociogenesis of Idiocultures

Deborah Downing-Wilson’s research explored the ways small group cultures are created, common understandings among previously unacquainted individuals are achieved, and the importance of inter-cultural interaction for the formation of a cultural identity. She conceptualized the genesis of culture as a collective narrative process – a creative meaning making endeavor that entails ongoing negotiation and adaptation; affective investment; the synchronization of previously learned systems of symbols and practices; the development of new, hybrid practices; and the formation and definition of group boundaries.

The following selections from her book about this project (2011) provide a taste of the processes she observed:

As a research tool I modified the BaFa’ BaFa’ cultural simulation game, designed by Gary Shirts (1977), which has been widely and successfully used for three decades as a tool for teaching cross-cultural sensitivity (Sullivan & Duplaga, 1997). The idea behind BaFa’ BaFa’ is to give participants an opportunity to experience cultural border crossing in a safe space, and to reflect on and unpack their experience without the prejudices and constraints that real-life border crossing often includes.

In the standard version of BaFa’ BaFa’, participants are divided into two groups. Each group spends about an hour learning a different set of cultural norms that will govern their interactions. The groups then exchange members for short periods of time in an effort to learn about the other group’s culture. The goal is to learn as much as possible about the other group’s values, customs and norms without directly asking questions ? much like we are forced to learn when we travel to a foreign country.

Because the two cultures in the simulation are vastly different (one was geared toward community spirit and sharing, the other was focused on personal achievement) there is ample potential for misunderstanding when moving from one group to the other. During the simulation, each group develops hypotheses about the other culture which are tested when the two groups come together in the end to talk about their experiences.

I was intrigued by the reports of a heightened polarization, or stronger-than expected affinity with one’s group that formed after very brief periods of ‘enculturation’ in BaFa’ BaFa’. It appeared as though BaFa’ BaFa’ contained the necessary ‘seeds’ (a few simple rules and artifacts) for planting small group cultures.

BaFa’ BaFa’ was originally developed as an experiential teaching aid, not as a research tool. In order to address questions related to the ways that small cultures come into existence, persist and are transformed over time, the BaFa’ BaFa’ I extended the time frame of the simulation. The bi-weekly scheduling of a university course provided the basis for thinking of the sequential class meetings as generations of cultural experience, where solutions to problems developed in one meeting could be accumulated and passed on in the next. I hypothesized that if I slowed down the simulation and let the two cultures evolve over the academic quarter, the participants would have the opportunity to come to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of cultural processes, as well as the time to reflect on and write about those processes in weekly field notes and reflection papers.

The Initial Setting and Origin Myth

On the first day of class, the students (who had expected a standard lecture class, where they would sit and take notes, read, and take exams) were given a cursory introduction to the simulation including an origin myth. In the next class session, the students (now divided into two groups which were temporarily labeled “Alpha” and “Beta”) met in two different conference-style classrooms on adjoining floors of the same building on campus. When the Alpha group found their room, they were greeted warmly by “Mother Rachel,” who served toasted raisin bread and apple juice. The conference room furniture had been rearranged to create a casual and homey atmosphere. “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys was playing softly in the background. By contrast, the Beta group entered a “business meeting” conducted around a large table in the center of the room. They were greeted by Mrs. Wilson, the “banker.” Beta participants were treated with professional courtesy, issued pre-printed name tags, and seated at the conference table. Self-service water, coffee and donuts were arranged on a side counter.

Each group was told a bare-bones mythic fable from which their cultural narratives could be launched. The folk tale “Stone Soup” was chosen for the Alpha culture, the more communal of the groups. In this classic legend, a traveler enters a village of hungry people. Instead of asking for food, he produces a stone from his cloak, drops it into a pot of boiling water, and begins to smack his lips over the delicious soup he is preparing. As he attracts the attention of the townspeople, he convinces each of them to add a little of whatever bits of food they have in the house to his cauldron. In the end, there is indeed a lovely pot of soup for everyone to enjoy.

A tale based on the Old Testament “Parable of the Talents” was written for the Beta group. This story honors individuality and personal achievement. It tells of the aging leader of a financial institution who entrusts each of three valued employees with a large sum of money. Their task is to use the cash as they see fit, and to report at the end of the year on the status of their investments. The first employee builds a more impressive bank, the second saves the cash, and the third, through hard work and shrewd trades, doubles her investments. It is this third employee that is chosen as successor to the leader of the group.

These two classic tales were chosen to exemplify two different sets of values and two different lifeways. They were designed to provide different cultural frames of reference through which the students approached the tasks and situations they encountered as the enacted the simulation. They also served as ethical anchors for the two developing cultural groups. In order to insure that the students “got the message” from each of the parables, and to establish from the outset the practice of integrating the simulation events with the participants’ larger life narratives, the students’ homework assignment for this first day was to write their own one-page story, either actual or fabricated. Their story should capture some element of what they considered to be the “spirit” of their group.

In addition to an origin story and the contrasting cultural scenes sketched above, we provided the participants in each group with a bare-bones “cultural tool-kit”. These initial artifacts would serve two purposes in the simulation. First, the artifacts could be easily tracked as they were selectively deployed and adapted to meet the challenges the participants would encounter as the simulation evolved. Second, the two sets of materials and procedures would prescribe unique ways of interacting that could be readily learned by each group, but that could not be easily deciphered and duplicated by outsiders. One culture (Alpha) involved rigidly regulated social interactions, and work/games that required little expertise. In the Beta culture, participants were free to interact socially as they wanted, but their work/card game was complex and competitive. Descriptions and instructions were minimal, providing space for differential interpretation, expansion, and evolution of the rules and behavioral norms as the two cultures emerged.

Initial Results: Appropriation of the Origin Myths

The student responses following their first exposure to the origin myths of their group were our first bits of evidence that their initial cultural experience had been effective in communicating the core differences between the two cultures. We were fairly certain, given reports of the initial BaFa-BaFa simulations that some such process would take place, but we had little idea of how much cultural learning would occur. Nor could we anticipate what, in particular, the students would write about. The personal stories they told quickly indicated that the contrasting cultural systems were discernible across a wide variety of narrative contents.

For example, Alpha participant, Vivian, submitted a true story about being rescued by a group of helpful citizens when her mother’s car broke down on a rainy night with six-year-old Vivian, Vivian’s younger twin brothers, and grandmother on board. A man in a red pickup stopped to help, but Vivian’s mom was afraid and sent him away. The man returned with his wife, but her car was too small to fit the family and Vivian’s mom would not hear of splitting them up. He recruited his neighbor with a van, and his son who had some mechanical expertise, and together they were able to get the car running and the family to safety. In the final paragraph of her story, lchcautobiod below, note the explicit connections that Vivian draws between the Stone Soup parable, her childhood memory, and her own personal development in terms of how she intends to incorporate this new information into her future actions:

The man and his son must have figured out what was wrong with the car because they all showed up at Wendy’s before we were even finished eating. I have kind of forgotten all about that night, but my mom still talks about it sometimes, so I’m not sure if I remember the night or just her stories about it. When I heard the Stone Soup story yesterday I started to think about the fact that our bad situation that night was too complicated for one person to solve but it could only be solved if everyone did something. The man with the stone was kind of like the man in the red truck. He got a bunch of people to come together to help us. I think I will always remember that now and try to pitch in when I see people in need of assistance even if someone else is already trying to help out because sometimes we all need to be in this life together (Vivian, SS, 4/3).

Beta culture’s Bruno also tells a true family story, about his grandfather who owned a small salt company in Korea:

One day as grandfather was waiting to unload his salt from a barge in Inchon harbor it began to rain. In the rain a huge snake slithered up on the deck, causing the workman to run before unloading the salt. It rained for several days while grandfather worked frantically to keep his inventory covered and dry. When the skies cleared grandpa saw that the snake had actually been a large rope that had washed up, and that all of the other merchants’ salt, which had been unloaded in the rain, had melted away.

In his closing comments below, Bruno credits the happy outcome to his great-grandfather’s “persistent nature”, which is central value of Beta culture:

Only our great-grandfather’s salt was safe on his boat. The price of salt skyrocketed that day, more than four times the usual price. That day our great-grandfather made a large fortune thanks to the “snake” and the rain, and his persistent nature most of all (Bruno, FTC, 4/3).

After reading the students’ stories, we were satisfied that they had adopted the moral and aesthetic moods of their respective cultures and were able to generalize them across a wide range of social situations. These cultural currents would underlie the norms and practices that the students would engage in as the simulation progressed.

Following their initial session where they were introduced to the origin myth, the separate groups where they were exposed to the differing tasks and the cultural values embedded in them of their respective cultures.

The Work of a Stoner is all Play

The Alphas learned that their society was a benevolent matriarchy where warmth, affection and tolerance were valued above all else. Alphas were instructed to stand close, touch often, and show genuine concern for each other’s welfare. They were never, under any circumstances, to be impatient, unkind, angry, or aggressive. Alpha etiquette required clan members to greet each other fondly, and then move immediately into concerned inquiries and detailed discussions about the health, achievements, and wisdom of each other’s grandparents and other ancestors. Polite Alphas pay full attention to each other in conversation. Newcomers wishing to join a conversation in progress should listen quietly for a while to be sure that they can contribute appropriately, and then wait to be invited before speaking.

Bob Marley singing “don’t worry ’bout a thing” in the background pretty much sums up the rhythm that emerged inside the Alpha culture. We should not have been surprised when the Alphans immediately named their group “Stone Soup” and began referring to themselves as the “Stoners”. The Stoners learned that theirs was a wealthy tribe. In fact, resources and money were so abundant that neither worry nor work would play a visible role in daily life. A large pot of “gold” coins was displayed prominently in the center of the room. The Stoners were told that they should take anything they needed from it, but to be sure and put back whatever was left at the end of the day. The hoarding of money, or any display of attachment to, or particular interest in money, was considered extremely rude.

The Stoners were divided into four “families” and issued explicit rules about appropriate inter and intra-family conduct. Their days were spent enjoying each other’s company. The room that the Stoners called home was stocked with “comfort food” as well as a variety of craft supplies, like rough woven cloth, needles and thread, yarn, markers, glue and such, all or none of which the players could use as they wished. Stoners could eat and drink, play their card game, listen to music, sing and dance, or engage in craft projects, but they should never forget to value friendship and camaraderie above all.

For Beta’s It’s all about the money

Betans learned their worth was determined during the 15 minutes that they would spend on the trading floor each day. A successful Betan must be honest, consistent, persistent, and able to drive a hard bargain. Students would discover on their own that time management was an important element of Beta success, as the more transactions that could be accomplished during a single trading session, the more opportunities a Betan would have for increasing his or her wealth.

While the Stoners were making nice, the Beta group chose the name “Fair Trade Cartel,” and began calling themselves the “Traders”. The Traders were grouped into four trading teams, and while personal achievement was their ultimate goal, success was only possible through in-team cooperation and between team-competition. The majority of their time was spent trying to gain the competitive edge necessary to be successful on the trading floor.

Trading cards were distributed, along with a warning: the trading language and the rules of trade that were about to be orally shared with the group were closely held secrets that conferred huge advantages on the trading floor. This insider knowledge was never to be written down or shared with anyone who was not a Trader. Any leakage of these details would greatly jeopardize the success of the group, and limit the players’ earning potential. It’s important to note that no penalties or procedures for enforcing the rules were introduced, or even suggested. This left the players free to create, or not, whatever means of policing each other they felt necessary.

The Traders learned that all business transactions must be accomplished using a special set of words. This system sounded complex when heard for the first time, but it was actually quite simple when understood. There were only thirteen permitted words, six for colors and seven for numbers. The card game that the Traders were about to learn was a lot like “Go Fish” and would require the players to describe the color and number of the cards they were looking for.

An uninformed listener might walk into an animated trading conversation, which sounded terribly complex due to the almost infinite possible combinations of first initials and vowel sounds. In reality, only 13 different words were being communicated. After a few awkward attempts, most of the students picked up producing the language quickly. Understanding each other was a different skill altogether, and took a little longer to master, but before long, all of the Traders became fluent in “Tradolog”, as one Filipina student dubbed the language.

At the end of the first week of the simulation class a passersby would have mistaken the departing Stoners for a group of close friends leaving a party, complete with hugs and fond farewells. The Traders strode out the door with apparent purpose and direction. Tim was singing “Ain’t nothin’ gonna breaka my stride?” to the great amusement of his Traders teammates.

Already Stoned! No-shows, Tardiness, Boredom and Lack of Purpose

Despite our insistence on punctuality, and the students’ understanding that there would be a quiz on the assigned reading at 8:00 am, seven Stoners were missing at 8:15. Five students would show up before the class was over, but two just did not bother to attend. The beginning of class had been designated as the only time that the cultural rules could be explicitly discussed. This meant that absent and tardy students might miss out on some of the information necessary to participate fully in their culture; they might never become fully contributing members of their culture. This could seriously jeopardize the students’ progress and that of the entire simulation. We were left to question how, in a culture that is intended to be relaxed and anything but time-conscious, can we instill a desire in the students to be on time for a class that meets at eight o’clock in the morning?

Already into it! Present, Punctual, Engaged

On the same day the Stoners were dealing with lateness and no-shows, the facilitator for the Traders arrived at 7:45 a.m. to find an animated group waiting outside the door of the conference room, eager to begin the simulation. As soon as the door was unlocked, the students rushed in and began re-arranging the furniture to create a “trading floor”. Each of the small trading teams clustered in a different corner of the room. When donuts arrived the students quickly helped themselves from the table in the back of the room and returned to their corners without conversing with anyone outside of their immediate group. Sam hurried in at 8:03. He was winded and apologized profusely because his bus had been late, and he had sprinted across campus to get there as soon as possible. Everyone else had arrived on time. The Traders cleared the center of the room and retrieved their sample sets of trading cards from the banker’s file boxes. A small silver counter bell was introduced to mark the beginning and end of the exchange sessions. When the bell was tapped three times in quick succession and the announcement “the trading floor is now open” was made, everyone immediately sprang from their seats and the negotiations began. We were more than a little surprised at how unselfconscious the students seemed to be about using the rather silly language and body gestures that proper trading required.

In both cultures, we were able to see the rapid appropriation of local cultural practices that were consistent with the “cultural starter kits” we had provided. In the weeks to follow, the interactions between the two groups produced unexpected ruptures in the easy flow of the activities. These ruptures revealed many ways in which culture mediates both social interactions and the linkages between social interactions and the societal processes of which they are a part and which they constitute. A great many lessons were learned from this cultural simulation.

Collaborative Video Production as a Tool of Participatory Action Research

Camille Campion’s work was a direct outgrowth of the research conducted at the Town & Country Learning Center. As we wrote in Chapter 13, the strategy of mutual appropriation we used in that project created a runaway object — the needs of the community were so pressing and pervasive that it threatened our ability to specify the rapidly growing and changing object of analysis. One problem that dramatically presented itself to us was the lack of safety of the children and youth traveling by foot from home to school. Following this thread, we found ourselves at a school meeting where we learned about a local, community-initiated project to insure student safety going to and from school. Camille became attached to this issue, as recounted below:

In 2008, I began conducting a Participatory Action Research (PAR) project with Project Safe Way, a resident-led non-profit organization whose main purpose was to ensure students’ safe passage to and from school. I started working with this group as a result of having participated as a graduate student researcher at T&CLC for nearly two years. Over time, it became apparent that we needed to also focus our attention outside the walls of the center and seek to understand the local environment in which the students lived. On several occasions during my site visits, students voiced concerns about their safety, particularly on their way to and from school. They had been victims of hit and runs, theft, sexual harassment, and other abuses.

As you can expect, these were troubling stories to hear. I wanted to do something about it. I decided to learn more about the neighborhood and sought to gain local knowledge alongside residents in order to imagine possibilities and co-create strategies for local change. This line of events led me to my doctoral PAR project, which I conducted using what I have called a Collaborative Video Production (CVP) method.

From September 2008 to May 2009, I attended the weekly Friday morning meetings of Project Safe Way. The group had obtained a grant from a local community foundation which served as the meeting place for some 20 adult volunteers. During these meetings, I mainly participated as an observer taking notes about what the group discussed. I learned that they monitored a designated area and had “corner leaders” wearing bright yellow vests and carrying walk-talkies on eighteen corners surrounding the local schools. Each corner leader would report on the happenings of the week – harassments, trash, infrastructural issues, deviant characters, drug use, etc.

I would arrive a little early and leave a little late so as to causally talk to the group members; informally, often over coffee and bagels, I got to know them better as they did me. I was able to begin to gain the members’ trust by being consistently present and taking an active interest in their work. The rapport we built during this initial period played an important role in the continuation of the project and the members’ prolonged engagement. This period marks the first phase of the collaborative video production project, although at the time, we had not yet decided to create a video together.

My colleague from UCSD, Makeba Jones, also attended PSW’s meetings as part of a separate project. She and I decided to interview the members about their life stories, perceptions of the neighborhood, and local ways of making-meaning. In order to make the interview experience meaningful to the members as well, we decided to film their story telling and then use their videos to co-produce a short promotional video which the group could use to introduce the program to new communities and for getting additional grants.

Many of the members, as they often recounted during meetings, saw their participation in PSW as a way to “give back” to the community — some were ex-gang members, others ex-drug users, and they all wanted to provide better opportunities for the youth than they had experienced. Their stories were inspiring, and we wanted to capture them, learn from them, and have them learn from each other. Over several weeks, Makeba and I set up and interviewed 13 members. After filming and collecting the interviews, they were transcribed and I analyzed each text using an experience-centered approach. Interesting patterns and stories emerged here which greatly contributed to my understanding of PSW and also my understanding of their understanding of themselves. The interview and analysis of the texts marked Phase II of the CVP project.

It was during Phase III, the collaborative editing of the video, that many of the group’s dynamics, of which I was formerly unaware, were made visible to me (a year and a half after I began working with PSW!). A subset of members and I worked together weekly to produce the video. (It is important to mention here that PSW had undergone some structural changes a few months earlier. There were now small task forces who spearheaded varying projects, such as creating positive relationships with SD Police. These task force leaders made up the editing team.)

After we created a storyboard, I provided the team with transcripts of the interviews so we could decide which segments, lchcautobios, etc. to use in the video. Surprisingly, they did not want to use much of the material that was recorded by the corner leaders’ interviews. I had assumed that these members, who played such a visible role in the group’s activities, and whose stories we had found so compelling would be given a prominent role in the video. Instead the production group asked me to interview other folks who were peripherally part of PSW but who held positions of power in the community (i.e., school principals). I found myself in the position of arguing that they must give voice to the PSW members who worked “on the ground” – folks whose identities seemed deeply intertwined with their role in PSW (as I learned during Phase II).

During this editorial work, as those present discussed what to include and what to exclude from final video, a great many tensions that remained hidden in all of my previous experience within the community came to light. Competition for work with the sponsoring foundation, old conflicts, concerns about allowing people with criminal records to be seen in the films, and many other such observations opened up a whole, previously missing layer of information about the community and the problems it confronted. Among the lessons I learned was how the process of creating the final video product transformed the multi-voiced collective narrative of the project members into a cleaned up master narrative that was heavily influenced by the parent organization which funded PSW.

For a complete account of this work, see Camille’s thesis: Collaborative video production as method, process and text in participatory action research.

Understanding Online Affinity Groups through the Lens of Activity Theory

Rachel Cody Pfister’s thesis project followed several years of research pursuing LCHC’s long-term interest in using the Internet for organizing collective activity that promotes learning and community. This work indicates how far the Lab had moved from its early days using store-and-forward methods described in earlier chapters. The text below is taken from the abstract of her thesis, Unraveling Hogwarts: Understanding an Affinity Group through the Lens of Activity Theory.

My dissertation used the framework of activity theory to understand the development and evolution of Hogwarts at Ravelry (H@R), an online group devoted to the interests of Harry Potter and fiber crafting (knitting, crocheting, weaving, and spinning yarn). The organization and practices of H@R are inspired by the popular Harry Potter book series, and members role-play as students of their own fiber crafting version of the magical school of Hogwarts. They take classes on Harry Potter topics, write reports, take tests, and craft items to submit as assignments.

I argue that H@R is both an affinity group and a wildfire activity. It is an interest-driven community with particular characteristics that foster learning and production. It has a membership that is diverse in members’ individual needs and goals, but who are united through the shared values and collective object of the group. A core value of H@R is supporting individual members as well as the shared collective object.

The dissertation takes as its moment of departure a series of events in H@R’s fifth school year, when participation declined and H@R leaders used role-play to reorganize the group’s practices and rules. Drawing from three years of participant observation, interviews, and archival research, I then trace H@R’s development from its creation through the end of its seventh school year.

I argue that the participation problems of Year 5 were due to underlying contradictions that gradually shifted the system of activity away from the group’s original collective object to a new object that failed to support all members. Collective discussions about this shift resulted in an expansive cycle of learning, through which leaders and long-term members successfully analyzed and rectified the accumulating contradictions that were destabilizing and threatening the future of the group.

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the possibilities and outcomes of affinity groups such as H@R, but there is little understanding of how these groups develop and are sustained. I address this gap by making visible the process by which H@R developed, evolved, and was sustained over several years despite tensions and changing members and needs.

General Semantics and the Cultural-Historical School of Psychology

At roughly the turn of the millennium, an unusual opportunity to re-examine questions of language and thought that had featured in the Lab’s concerns since “before the beginning,” when Gay and Cole began to conduct research in Liberia (see Chapter One). A local entertainer and businessman, Sanford Berman, had approached UCSD to set up an endowed chair in General Semantics. Mike, in his capacity as a Professor of Communication, was made the faculty contact person who was tasked with helping to locate the endowed chair. The Department was looking to hire a prominent new faculty position, and an endowed chair.

The Department searched for an appropriate candidate, but the person it wanted to hire was turned down by an all-campus committee that did not think the person qualified for the chair. The second candidate, who was qualified for the chair, turned the Department down. In the third year of the search, a former member of the Department asked to return to UCSD. There was no open line — unless Mike took the Chair.

Fortuitously, Sanford Berman was both a successful entertainer, a hypnotist whose stage name was Dr. Dean, and a graduate student of Irving Lee, a devotee of general semantics. Equally fortuitously, Mike was familiar with general semantics from his days as an undergraduate. Mike also knew of A.R. Luria’s research using hypnotism as an experimental treatment in his work on the combined-motor-method.

Due the difficulties of locating a suitable external candidate coupled with the need for an open line in the department, Mike eventually became the Sanford I. Berman Chair of Language and Communication, a title which has since been taken over by Carol Padden.

The endowment from the Chair provided a modest amount of money for research support. This money was spent to study the ideas of general semantics and assess how they might be used to fit into the curriculum of the Communication Department (Mr. Berman’s primary concern was to create a large undergraduate course that was taught regularly). Given that general semantics had long ago become disfavored in academia, this was not an easy task. The first results were a set of summaries of the major ideas of Alfred Korzybski and a symposium at a meeting of the International Communication Association, meetings in which several faculty members at UCSD discussed the relation of their ideas to those of general semantics. This symposium engaged with the dictum, first coined by Korzybski, “the map is not the territory.” Paper topics included: 17th Century map making (Chandra Mukerji), ontology and cyberculture (Thierry Bardini), lexical knowledge without a lexicon (Jeff Elman), and the contributions of General Semantics to a unified theory of human communication (Michael Cole and Etienne Pelaprat).

In 2010, Greg Thompson obtained a post-doctoral fellowship both to follow up on the theoretical work that his predecessors had done in putting together the summaries of general semantics ideas and to create the kind of undergraduate class that Mr. Berman aspired to. Over the course of this work, Greg was able to create a successful undergraduate class and to piece together key ideas present in general semantics as developed in the second half of the 20th Century and the ideas of L.S. Vygotsky of a few years earlier.

Below is Greg’s summary of some key ideas in general semantics and their relevance to cultural-historical theories of human psychology:

General Semantics is a field of study developed in the early 20th century. General Semantics (hereafter “GS”) was founded on the idea that language and thought are interdependent processes. GS founder, Alfred Korzybski applied this insight to a number of everyday problems varying from individual psychological problems such as psychosis to massive societal problems such as intercultural misunderstandings and global warfare. In its heyday in the middle of the 20th century, GS drew a wide array of scholars from many different disciplines including figures such as: Edward Thorndike, Margaret Mead, Leslie A. White, Benjamin Lee Whorf, Rudolf Carnap, Dorothy Lee, Charles Morris, e. e. cummings, Carl R. Rogers, and Gregory Bateson.

Two core concerns unite GS and the interests of the lab. The first of these is semiotic mediation. Semiotic mediation refers to how our understanding of the world is mediated by language. In this vein, Korzybski argues that thinking and speech are interrelated processes, and he thus offers a conception of semiotic mediation that is very similar to the conception of semiotic mediation that Vygotsky proposed and which has been a central and long-standing theme of the lab’s work.

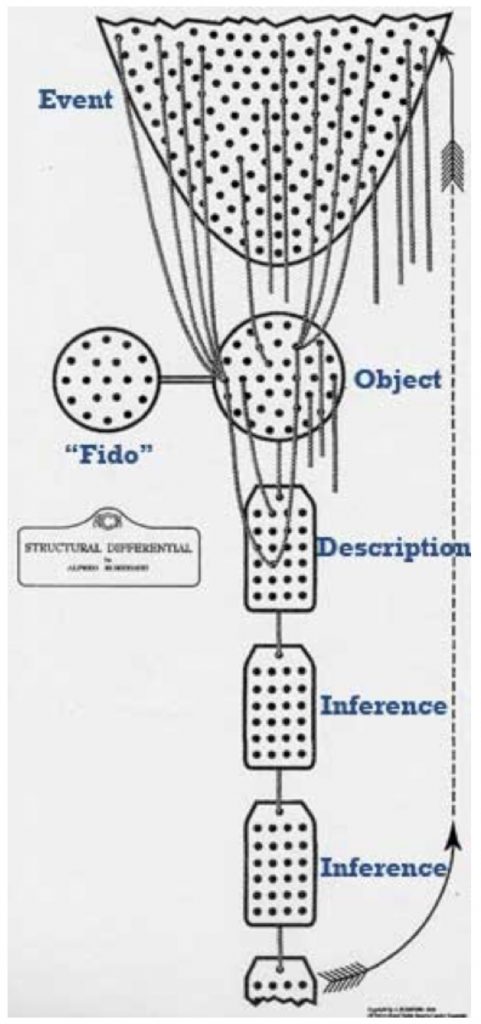

The concept of semiotic mediation is perhaps best illustrated in a diagram frequently employed by Korzybski (see Figure 1) and referred to as the “structural differential.” Korzybski often insisted that the diagram should be represented in three dimensions so that the student can feel with their hands the different levels of abstraction. But for present purposes, a two-dimensional representation will do.

As a whole, the diagram is meant as a representation of the human process of abstracting. In the diagram the top level represents reality in all its complexity (Korzybski would refer to this as “submicroscopic reality” in order to make it clear that there is much about reality that humans cannot grasp). The infinitude of reality is indicated by the broken parabola which opens upward, suggesting it extends indefinitely. The strings hanging down from the broken parabola down to the first circle indicates the level of objects that are perceived. The strings from the parabola to the circle indicate that when we identify reality in terms of objects, some aspects of infinite reality are picked out while other aspects are neglected (B1 and B2 in the diagram). Yet, this is only the beginning of abstracting and does not capture what our uniquely human capacity for abstracting.

The next level down is the level of the Label (L in the diagram), i.e., the level of language and the word that refers to the object. The strings from the object to the label again indicate that only some aspects of the object are picked out by the label. The next level (L1 in the diagram) indicates the level of inferences and statements which are made about the label, and thus about the object. From there, the string of continuing inferences and statements represents the fact that further inferences and statements can be made about preceding abstractions ad infinitum (thus, Ln). According to Korzybski, it is this possibility for infinite reflexiveness that is what makes this process of abstracting distinctly human.

Finally, the bottom-most level (Ln) connects back to the broken parabola representing reality. This suggests that the process of abstracting feeds back into reality, shaping and changing the reality that can then be understood in new ways.

This model that Korzybski offers provides a way of understanding human epistemology writ large, that is, it is intended a way of understanding how we perceive and understand reality. Of particular interest to General Semantics was how this model of human abstracting processes can help us to understand how we perceive and understand fellow human beings. Applying the structural differential to our understanding of people points to important potential troubles when we rely on labels for understanding other people. The structural differential points to the fact that when we understand a person (Oh) by a given label (L), we are likely to fail to understand the vast majority of who that person is (B1, B2, ? Bn). For example, we might consider how a label such as “Muslim” tells us only some small aspects of the person that it refers to while leaving other aspects of that person hidden from view (e.g., age, gender, career, ethnic and national background, family status, sexual orientation, political leanings, etc.).

In addition, General Semantics points to the problem of our semantic reactions, that is the immediate reactions of thought/feeling that we have to particular words and things. In this regard, General Semantics was applied as a form of therapy to help people overcome their irrational semantic reactions (hence, the title of Korzybski’s book Science and Sanity). Once one better understands the process of abstracting that is represented in the structural differential, then one can begin to understand maladjusted semantic reactions and can become a saner and psychologically healthier person.

A second core concern that the Lab shares with GS is the GS notion of the non-essentialist human subject. This concern flows from the application of the structural differential to the labeling of humans. Rather than seeing humans in terms of psychological labels, humans are seen as relational processes that develop and change across time and context. The temporal nature of human development and change is captured by the GS concept of indexing. The idea is that we index any references to persons so as to recognize that we are making reference to that particular person, say Eve, at a particular time, e.g., Eve2017. The contextual nature of human development and change is captured by GS scholar and anthropologist Gregory Bateson’s notion of the “organism-in-the-environment” (This critique of the notion of an essentialized subject was particularly notable in the work of Dr. Berman and his dissertation advisor Dr. Irving Lee who both criticized the common racial and ethnic labels of their day (e.g., Berman 1982, Lee 1942, Lee 1956). In this connection, many leading GS scholars were involved in early forms of anti-discrimination movements.

As Sanford Berman Post-doctoral Fellow, Greg took up both the concern with semantic reactions and with labeling. In one paper (Thompson 2014), he analyzes an instance of labeling as it happens in a tutoring session in order to show how this process of abstracting works in actual human interactions. The tutoring session is between a white female college tutor and an African-American high school student. The student has been struggling with percentage problems on the ACT exam and they are working out of a book of questions from old ACT exams. At the beginning of the tutoring session the student has what Korzybski would call a semantic reaction to the mere thought of the test. She says “I just look at the test and my brain freeze[s].” The tutor offers her a different interpretation suggesting the label for the student of “smarter than you think”. When the student first approaches the math problems, she is very hesitant and uncertain. Yet, by the end of the session, she confidently and assertively approaches these problems. The central question of the paper is: what were the conditions of the interaction that contributed to this transformation?

Greg argues that one of the central contributions to this change was the nature of the local interactional context that had been established between the tutor and student – what Erving Goffman (1974) referred to as the frame. The tutor and student together manage to build up the framing of this particular tutoring session as a kind of “rehearsal” that captures both the seriousness of the testing situation and the support of a friendly encounter. As Goffman noted, rehearsals involve a decoupling of events from their usual “embedment in consequentiality” such that “muffing or failure can occur both economically and instructively” (Goffman 1974, 59). At the same time, the seriousness of the rehearsal suggests an isomorphism with the seriousness of the test itself, thus allowing for the transfer of understanding from the context of the tutoring session to the context of the text. In the end, this framing of the interaction as a rehearsal provides the context in which the label “you’re smarter than you think” (when said by the tutor to the student) can effectively be made to stick to the student, while also effectively changing her semantic reaction to the subsequent test questions such that she now encounters them confidently and assertively.

This work also connects with another of the lab’s central themes: the importance of contexts for motivation. As Alexander Luria noted: “Many observations support our view that the consideration of the voluntary act as accomplished by ‘will-power’ is a myth, and that the human cannot by direct force control his behavior any more than ‘a shadow can carry stones.’” Instead, Luria suggested: “Our researches convince us that such a control comes from without, and that in the first stages of the control the human creates certain external stimuli, which produce within him definite forms of motor behavior. The primordial voluntary mechanism evidently consists in the external setting, the production of cultural stimuli mobilising and directing the natural forces of behavior.” In other words, Luria’s suggestion here is that the external settings in which we find ourselves are very consequential for shaping our behavior. Responding to a slightly different concern (here, the concern that cognitive processes are particular to a given cultural group), Cole, Gay, Glick, and Sharp (1971) similarly noted that “cultural differences in cognition reside more in the situations to which particular cognitive processes are applied than in the existence of a process in one cultural group and its absence in another” (p. 233). Greg’s paper similarly points to the power of contexts in affecting cognitive processes and enabling the student’s transformation.

Two additional papers by Greg further developed the joint concern of GS and the lab with the effects of small scale communicative contexts upon individuals. Thompson and Dori-Hacohen (2012) analyzed the affective and interactional consequences of interactional framings, demonstrating how these are unwittingly built up in conversation such that they have serious consequences for the conversational participants. Work by Stone and Thompson (2014) took up this same concern with the supra-individual context of learning in a kindergarten classroom. This work developed a conception of “classroom mood” as another example of a supra-individual context that enables and constrains the possibilities for student learning.

These three papers also point to the work mentioned above and below by Deb Downing-Wilson, Rachel Cody Pfister and Tamara Jackson Powell, whose work illustrates the power of contexts to transform people that are subsumed by those contexts.

Simulations as a Tool of Medical Education

Tamara (Tammy) Jackson Powell was one of the early participants in the research conducted at the Town and Country Learning Center (Chapter 13). As a former collegiate athlete, Tammy led activities that combined core academic activities such as the use of elementary mathematics with other non-academic activities such as a (relatively) long distance running activity. Early on, these activities were seen a partial response to the health problems facing the community.

In the fall of 2008, LCHC was undergoing review as an Organized Research Unit on campus, and through this process connected with William Norcross, a clinical professor in the departments of Family Medicine and Public Health. Norcross had a long-standing interest in community-based health interventions and took interest in the health education activities forming at Town and Country Learning Center. He connected Powell with Lindia Willies-Jacobo, the incoming Assistant Dean for Diversity and Community partnerships at UCSD’s School of Medicine.

Willies-Jacobo was also the director of the Program for Medical Education – Health Equity (PRIME-HEq), a learning community focused on training future physicians to address health disparities. The PRIME-HEq program was part of a UC system-wide effort to train physicians to better meet the needs of the diverse Californian population who are traditionally underserved by the medical system. A partnership developed between the PRIME-HEq program and LCHC to offer two community-based health education programs: a sex education course for teens at the Town and Country Learning Center and a teen wellness program taught at TCLC’s local high school, Lincoln High, called Healthy Minds Healthy Bodies.

For Powell’s dissertation, she examined the origins, development, and sustainability of the Healthy Minds Healthy Bodies program. By means of participant-observation, interviewing, and video-analysis, she observed how, over the course of three-and-a-half years, the program transitioned from a student led, volunteer-based health education service project to a required course for first-year medical students participating in a new underserved medicine learning community. With this transition of purpose and institutional status came other unforeseen changes in, and contradictions between, the practices, tools, and procedures that medical students used to carry out the operation of the program. This also corresponded with a shift in the atmosphere of the training sessions, which became more formal, less interactive, more evaluation-focused, and less simulation-based.

These changes were connected to evolving and at times conflicting expectations, goals, and objectives for Healthy Minds Healthy Bodies, which was a part of multiple activity systems (the School of Medicine, PRIME-HEq, graduate student life, Lincoln High, etc). Powell applied cultural-historical activity theory as a tool for analyzing these organizational contradictions, which allowed her to not only investigate the origins of the tensions, but also to help stakeholders imagine future trajectories for the program. She argued that the original objective of the program was volunteer community service and that as it became a required elective course, experiential learning emerged as a new objective. Separately, these were competing interests. However, it was possible to synthesize these orientations in the form of service-learning. Expanding the program’s motivating object into service-learning could create synergy and coherence for the multiple actors and systems involved, as well as help to address contradictions within the program.

Powell’s research into service learning in higher education was contemporaneous with and substantially overlapped with the work of Deb Downing Wilson. Powell also worked with PRIME-HEq to refine their simulation-based training modules, which tied in simulation research, which was of great interest in the lab with Rachel Cody Pfister and Deb Downing-Wilson.

Chapter Compositors: Camille Campion, Rachel Cody Pfister, Deborah Downing-Wilson, Greg Thompson, and Mike Cole.

Back to Chapter 14

Read more at the Projects Page

Engage in the discussion on the LCHC Autobio Forum