“Poverty, whatever can justify the designation of ‘the poor,’ ought to be a transitional state to which no man ought to admit himself to belong, tho’ he may find himself in it because he is passing thro’ it, in the effort to leave it. Poor men we must always have, till the redemption is fulfilled, but The Poor, as consisting of the same Individuals! O this is a sore accusation against society.”

–Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1834; unpublished papers)

The Educational “Achievement Gap”

The research summarized in Chapter One was carried out within a global framework of concerns about economic development, particularly in what was then termed “Third World.” Sponsorship of this research was part of the larger Foreign Aid effort of the United States (U.S.) –because of the role it played in the founding of Liberia, and as a part of the general program of the United Nations (U.N.). Members of the research group were also frequent participants in the training programs of the local Peace Corp effort, and they consulted regularly with other U.S. and U.N. agencies concerned with education. Drawing all of these efforts together was a focus on developing educational reform that was informed by a better understanding of the impediments to acquiring a modern education.

Viewed through the prism of American domestic concerns, this research was part of a contentious national debate about racial inequalities. There was national disappointment when desegregation of the schools, begun by Brown vs. Board of Education (1954), had failed to eradicate marked ethnic differences in school achievement a decade later. America had entered an era of concern about the educational “achievement gap” which remains with us to this day.

The Moynihan Report

To understand the context and spirit of the times, it is helpful to consider the rarely cited prelude to the influential Moynihan Report written by sociologist and then Under-Secretary of Labor Daniel Moynihan, in 1965:

“The United States is approaching a new crisis in race relations.

In the decade that began with the school desegregation decision of the Supreme Court, and ended with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the demand of Negro Americans for full recognition of their civil rights was fully met…

In the meantime a new period is beginning.

…In this new period the expectations of the Negro Americans will go beyond civil rights. Being Americans they will expect that in the near future equal opportunities for them as a group will produce roughly equal results. This is not going to happen. Nor will it happen for generations to come unless a new and special effort is made…

…The most difficult fact for white Americans to understand is that in these terms the circumstances of the Negro American community in recent years has probably been getting worse, not better…”

Moynihan’s diagnosis of the situation was that social conditions imposed upon Black Americans had brought about a crisis in socialization of the young by disrupting Black family life. He put the matter as follows:

“The fundamental problem, in which [circumstances are getting worse] is most clearly the case, is that of family structure. The evidence “not final, but powerfully persuasive” is that the Negro family in the urban ghettos is crumbling. A middle class group has managed to save itself, but for vast numbers of the unskilled, poorly educated city working class the fabric of conventional social relationships has all but disintegrated…So long as this situation persists, the cycle of poverty and disadvantage will continue to repeat itself.”

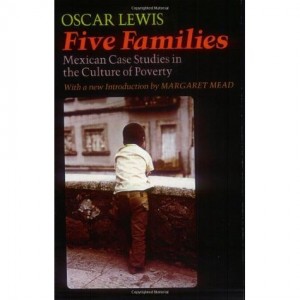

In making this argument, Moynihan drew upon the work of Oscar Lewis, who had conducted years of research among impoverished people in Mexico, South Asia, Puerto Rico, and New York City. Lewis hypothesized that a “culture of poverty” emerges when a capitalist system that marginalizes unskilled workers (and makes escape from their circumstances remote) is combined with a kind of social structure marked by the absence of compensatory social supports (e.g. extended family networks, kin or clan relations, etc.). Moynihan (1969) integrated Lewis’s approach into his own in the following terms

impoverished people in Mexico, South Asia, Puerto Rico, and New York City. Lewis hypothesized that a “culture of poverty” emerges when a capitalist system that marginalizes unskilled workers (and makes escape from their circumstances remote) is combined with a kind of social structure marked by the absence of compensatory social supports (e.g. extended family networks, kin or clan relations, etc.). Moynihan (1969) integrated Lewis’s approach into his own in the following terms

“The subculture [of the poor] develops mechanisms that tend to perpetuate it, especially because of what happens to the world view, aspirations, and character of the children who grow up in it” (p. 199).

Blaming the Victim

Moynihan and Lewis came under heavy criticism for “blaming the victim.” In particular, their critics took issue with the assessment that family life is a key way that the social forces that give rise to poverty are replicated. If we change what happens at this transmission point, argued Moynihan, and educational intervention can “break the cycle of poverty.” Moynihan was well aware of the theoretical implications of what he was claiming. In response to his critics, he argued that social conditions determine economic conditions, and he suggested that unjust social conditions facing families played a role in bringing about their economic conditions.

It is this particular view that was quickly attacked as “blaming the victim.” This was especially the case for Moynihan. Lewis’s work was often better nuanced, but not always. Both were aggressively critiqued, most comprehensively by anthropologists and sociologists who were disappointed with what was left out of their accounts. Often missing in this work was a description of the wide institutional networks of resources and relations available “and systematically not available” to different groups of persons by race, class, and neighborhood in large urban centers in industrial capitalist state societies (see Valentine, 1969 and a set of reviews in Current Anthropology in 1967 and 1969).

Alternatives to Theories of Cultural Deprivation

At the same time that social theorists were disputing theories of cultural deprivation, American psychologists were developing theories and methods that could supply the data for conjuring up what might be happening in the heads of children raised in environments seemingly injurious to their development.

The liberating news of the new psychology is that it was escaping a mindless (yes, in both senses) behaviorism. Instead, psychologists began to take into account the lively organisms (humans especially, but even pigeons and rats) that seemed to outrun the stimulus and response schedules that behaviorists were using. This shift included a rush to research on the cognitive lives of children and their development to maturity. Jean Piaget loomed large. So too did his critic, Lev Vygotsky, who started to gather attention (although only a taste of Vygotsky’s writing was available in English).

The bad news that followed these developments is that they were forced into political action before they were ready, that is, before the research community had the time and data necessary to understand the limitations of the theoretical and methodological advances they were beginning to organize. The work of George Miller, Noam Chomsky, Herbert Simon, and William Estes were all crucial to this effort, but the work of Jerome Bruner (1961) took center stage in the effort to bring the findings of cognitive psychology to education.

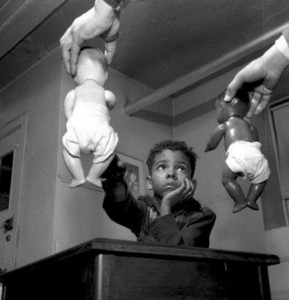

A crucial argument in the Brown vs. Board of Education decision rested on experiments conducted by Kenneth and Mamie Clark where Black children identified themselves with white dolls.

Two lines of academic research seemed to dominate the discussion: one arising in anthropology around the concept of a “Culture of Poverty” and the other arising out of psychological research around the idea of “Mediated Stimulus-Response Learning.” For a moment, they converged to provide an explanation of how poverty and marginalization slowed development. They also offered insight into the strategies that should be adopted to create curricula to help mitigate the recalcitrant problems of educational inequality.

The Supreme Court had finally brought the Declaration of Independence and the end of the Civil War together with the 1954 Brown vs. The Board of Education ruling against segregated schools. This was going to take work: from declarations to demonstrations to new kinds of education in new kinds of classrooms. The political demands and opportunities that were suddenly foisted upon experimental psychologists were extraordinary. It seemed as if the very soul of democracy was at stake, and that educational psychologists had the materials to guide the way.

War on Poverty

Everything was up for grabs (or could be), if only the way could be cleared. And so came a “War on Poverty.” One of the major “weapons” used in this “war” was to provide poor children with a high-quality head start during early childhood so they could succeed in school. Included in the package of Head Start interventions were programs focused on the health of the children and their families, as well as programs supporting adults in their roles as parents and breadwinners. However, it was the intellectual development and school achievement of minority children, especially IQ test measures, that became de facto criteria of success.

In the development of a psychology that served minority education, nothing stands out quite like Martin Deutsch’s (1960, 1967) account of the cognitive consequences of poverty on children’s performance and dreams of what to do once they have grown to maturity. Deutsch called for a strategy of supporting the child-family system, and this fitted the needs of the war on poverty. By the reigning system of beliefs, any head start provided to children would promote school achievement. Any attention to children that might even the playing field in early elementary school, it was argued, could make children eligible for more gainful employment in later life. Cognitive psychology moved quickly into educational policy in the hope that society could free itself from the “cycle of poverty.” Even economists were on board (see, for example, J.K. Galbraith’s 1958 suggestion that we were nearing the end of poverty and moving onto a more equalized society).

Culture of Poverty

The anthropological notion of the “culture of poverty” leaned strongly on an anthropological notion of “culture” popularized by such figures as Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. The culture of poverty was not, in Lewis’ terms, co-extensive with the situation of poverty. As formulated by Lewis, the culture of poverty notion referenced issues of the economic system and community organization.

When Lewis’ work was taken up within the context of the Civil Rights Movement and the War on Poverty, ideas that bore a family resemblance to Lewis’ notions were generalized to provide a rationale for a variety of interventionist social approaches. Both Lewis and Moynihan focused on linkages between poverty and its influences on family and community structure. By contrast, psychologists and educators charged with developing Head Start programming focused on child development through deliberate instruction (particularly during the pre-school years).

Social Class, Race and Psychological Development

The shift from socio-economic critique (embedded in the original Lewis formulation) to focus on child development was signaled in a series of publications (see Passow’s 1963 book, Education in Depressed Areas, 1963 and Deutsch’s 1967 book, The Disadvantaged Child, as examples among many). Here, we focus on a volume edited by Martin Deutsch, Irwin Katz and Arthur Jensen in 1968, Social Class, Race and Psychological Development. This book was dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr. and sponsored by The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI), facts that indicate the liberal roots of the Culture of Poverty movement. The book stands as an excellent summary of a decade of research on the cognitive consequences of the problems of inner-city youth. It also signals, as we shall see, the beginning of one of two possible responses to the increasingly visible failure of “Culture of Poverty” rhetoric to organize progressive social change. The first response started a return to a biological racism, while the second response focused on cultural difference not cultural deficit.

In the introduction to Deutsch’s 1968 book, Social class, Race and Psychological Development, Ernest Hilgard, a highly respected elder of the American academic learning theory movement in psychology, made explicit the ways in which government and philanthropic resources were being marshaled around the child development option:

“…The government stepped in…granting funds through The Office of Child Development, the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and other agencies. These funds, and those from private foundations, provide an opportunity for the behavior scientist to be of service, if he is ready… First, he can contribute to the understanding of the situation as it exists, examining our social structure, social classes, social mobility, the causes and consequences of poverty. Second, he can look to his research data to see what might be done to correct the effects of poverty on children, and he might also look for ways in which his science might help to ameliorate conditions that have resulted in poverty in the first place” (p. iii).

The articles that followed Hilgard’s introduction focused mainly on child development and intervention programs.

Psychological Theories of Cognitive Deficit

The idea that growing up in conditions of poverty produces an experiential deficit (cultural deprivation) that in turn produces a shortcoming in psychological functioning coincided with two significant lines of research then influential in American academic psychology. The first was a strong belief in the critical role of early experience in cognitive development. The second was a strong belief that well-designed regimes of learning-oriented training, particularly training organized around learning mediated by language, could compensate for the effects of early deprivation. Much of the foundational work on early experience and cognitive deficit had been conducted during the 1950s, primarily with animal models, but it was increasingly examined at the level of human development (a point of view that has again become dominant).

In his influential book, Intelligence and Experience, J. McVicker Hunt (1961) explicitly refers to the work of Lewis, arguing:

“First of all, cultural deprivation may be seen as a failure to provide an opportunity for infants and young children to have the experiences required for adequate development of those semi-autonomous central processes demanded for acquiring skill in the use of linguistic and mathematical symbols and the analysis of causal relations. The difference between the culturally deprived and the culturally privileged is, for children, analogous to the difference between cage reared and pet-reared rats and dogs… It should now be possible to arrange the institutional settings where children now culturally deprived by the accident of social class of their parents can be supplied with a set of encounters with circumstances which will provide an antidote for what they may have missed” (p. 323).

This same kind of linkage between a “culture of poverty” and impoverished intellectual development can be seen clearly in Cynthia Deutsch’s (1968) essay, Environment and Perception:

“The slum child is more likely than the middle-class child to live in a crowded, cluttered home-but not cluttered with objects which can be playthings for him. There is likely to be less variety of stimuli in the home, and less continuity between home and school objects. Where money for food and basic clothing is a problem, there is little for children’s playthings, for furniture in which to store the family possessions, and for decorative objects in the home. Where parents are poorly educated, there is likely to be less verbal interaction with the child, and less labeling of objects (or of the distinctive properties of stimuli) for the child. There is less stress on encouraging the production of labels by the child, and on teaching him the more subtle differentiations between stimuli (for example, knowing color names and identifying them). Thus, in the terms used earlier, the slum child has, in his stimulus field, both less redundancy and less education of his attention to the relevant properties of stimuli. As a result, he could be expected to come to school with poorer discrimination performance than his middle-class counterpart” (p. 79).

Deutsch, like Hunt, believed that proper training could help mitigate the effects of insufficient early experience. She pointed to research by Covington (1967) in which children were who designated as higher or lower status on the basis of their parents’ education were asked to discriminate between pairs of abstract stimuli. The findings showed a marked difference between the two groups. Happily, after fourteen sessions during which subjects were asked simply to look at the stimuli, the children identified as lower status improved twice as much as the upper status children, by then performing at an indistinguishable level. On the basis of this and related evidence, Deutsch concluded that with appropriate training, children could learn to make the kinds of perceptual distinctions that are important to education like Hunt, believed that proper training could help mitigate the effects of insufficient early experience. She pointed to research by Covington (1967) in which children were who designated as higher or lower status on the basis of their parents’ education were asked to discriminate between pairs of abstract stimuli. The findings showed a marked difference between the two groups. Happily, after fourteen sessions during which subjects were asked simply to look at the stimuli, the children identified as lower status improved twice as much as the upper status children, by then performing at an indistinguishable level. On the basis of this and related evidence, Deutsch concluded that with appropriate training, children can learn to make the kinds of perceptual distinctions that are important to education.

The task of developing pedagogical methods for designing compensatory early education programs was turned over to the field of experimental child psychology, which came into being in 1964. In its initial years, the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology published articles that aimed to transform existing theories and methods used to study the presumably universal laws of learning spanning the phylogenetic spectrum. This work depended heavily on mechanisms of learning that American stimulus-response theorists had initially developed to account for learning in rats, cats, dogs, and other animals (see Hull and Spence, for example). A basic assumption underlying this work was that apparently complex behaviors could be understood as occurring through the accumulation of stronger and more numerous stimulus-response associations shaped by differential reinforcement.

A particularly influential line of work drew its inspiration from a study by Margaret Kuenne (1946) and examined the phenomenon of transposition and its relation to learning in the development of children. Kuenne’s study reported on the ability of young children to learn that when shown two stimuli, selection of the larger one always produced a reward such as a piece of candy. Of particular interest was whether the children, having learned to make the correct choice between two stimuli of a particular scale, would also pick the larger of two new stimuli on a different scale from those that they had learned about already. This process was referred to as “transposition.”

A key finding of Kuenne’s study was that when asked to choose among two stimuli quite different in size from the originals, 3-year-old children failed to transpose the size relationship, but 6-year-old children transposed consistently. Kuenne proposed that the ability of the older children to respond to the relationship between stimuli, rather than the absolute properties of the stimuli, indicated that the older children were using language to mediate the relevant relationship. In her words (1946):

“This study hypothesizes that the simple mechanisms mediating transposition of response in infra-human organisms are identical with those responsible for similar behavior in children in the pre-verbal stage of development. With the acquisition of verbal processes, however, and the transition to behavior dominated by such processes, it is hypothesized that the child’s responses in the discrimination learning situation become keyed to words relating to the cue aspect of the stimuli” (p. 488).

It is easy to imagine how Kuenne’s study could be used to differentiate children of the same age, but of a different social class. If poor children did not perform up to middle class peers of the same age, a cognitive deficit would become visible. Even more intriguing is that in this setup, the mechanisms underlying the problem could be specified if it could be shown that middle-class and poor children were treated to quite different learning environments.

Sheldon White brought existing lines of evidence in favor of the “verbal mediation” hypothesis to argue that, from approximately five to seven years of age, the infusion of language into the processes of thought undergoes a fundamental change. Citing the work of L. S. Vygotsky and A. R. Luria, White (1965) characterized this “5-7 year shift” in the following terms:

“Presumably, the speech of the younger child is primarily a social tool for expressive and instrumental purposes. Toward the kindergarten years, speech becomes an instrument to regulate the self as well as the environment; the child talks to himself, effectively instructs himself, while problem-solving” (p. 206).

When taken up in the context of early childhood education as a weapon in the war on poverty, these ideas and their associated practices embodied the assumption that models of learning and instruction derived from behaviorist studies of rats and pigeons could be used to organize curricula for preschoolers from poor, marginalized communities. Although the “cognitive revolution” had dampened ardor for using stimulus/response learning procedures as the index of cognitive development, the notion that children living in poor environments are methodologically akin to rats in isolated cages, unfortunately, has not made its exit. It is worth pausing to consider the extremes to which this view could take people.

Perhaps the iconic case is Bereiter and Engelmann’s (1966) effort to create a model curriculum in Teaching Disadvantaged Children in the Preschool. In their book, Bereiter and Engelmann identify the principle of “direct instruction,” which was based on ideas linking the seeming disorder of life inside a culture of poverty (where ends and means do not meet) to learning theorists’ notions of how to provide an effective head start (where limited predefined ends are strung together until a child has a grasp of the wider situation). Bereiter and Engelmann saw this drama played out in the linguistic capacities of the children put into their care, and they moved to confront the problem directly:

“The speech of the severely deprived children seems to consist not of distinct words, as does the speech of middle-class children of the same age, but rather of whole phrases or sentences that function like giant words. That is to say, these “giant word” units cannot be taken apart by the child and re-combined; they cannot be transformed from statements to questions, from imperatives to declaratives, and so on. Instead of saying “He’s a big dog,” the deprived child says “He bih daw.” Instead of saying “I ain’t got no juice,” he says “Uai-ga-na-ju.” Instead of saying “That is a red truck,” he says “Da-re-truh.” Once the listener has become accustomed to this style of speech, he may begin to hear it as if all the sounds were there, and may get the impression that he is hearing articles when in fact there is only a pause where the article should be. He may believe that the child is using words like it, is, if, and in, when in fact he is using the same sound for all of them-something on the order of “ih.” (This becomes apparent if the child is asked to repeat the statement “It is in the box.” After a few attempts in which he becomes confused as to the number of “ih’s” to insert, the child is likely to be reduced to a stammer.) If the problem were merely one of faulty pronunciation, it would not be so serious. But it appears that the child’s faulty pronunciation arises from his inability to deal with sentences as sequences of meaningful parts. Even a sophisticated adult will have difficulty pronouncing a very long word if he is unable to deal with it in parts (the reader might take a try at EMPIANASROFLALILIMINLIAL, reading it aloud once and then trying to repeat it from memory). In the Cognitive Maturity Test, children are called upon to repeat sentences of varying degrees of complexity. The severely disadvantaged child will tend to give merely an approximate rendition of the over-all sound profile of the sentence, often leaving out the sounds in the middle, as is common when people are trying to reproduce a meaningless series-this in spite of the fact that the words themselves are often very simple, like “A big truck is not a little truck” (p. 34-35).

Later, Bereiter (1968) characterized the underlying logic and practical application of this approach in the following terms (which we again lchcautobio at length as a way to demonstrate the underlying assumptions embedded in the ways issues were being discussed):

“The language program we have used was originated by my colleague, Siegfried Engelmann. His outstanding achievement in this program, I believe, is a bold simultaneous solution to the problem of time, and the problem of priorities. As Engelmann saw it, the child’s primary need was for a language that would enable him to be taught. Once the child had that, you could go on and teach him anything else you pleased. Such a language did not have to be distilled from a recording of actual verbal behavior but could be constructed, much as Basic English was constructed, by a consideration of the needs it had to serve. Such a language could be taught to children in a relatively short time (in practice, two to six months), and it would then be possible to add the refinements of complete English and also to teach other things in a more direct and normal manner)” (p. 341).

Teaching disadvantaged children a miniature language that someone else has made up for them may sound a bit 1984-ish to the doubters among us. However, it should be noted that the principle of starting with a miniature system, which is part of but more easily grasped than the entire system, is a respectable and widely used pedagogical device. Reading instruction that begins with a limited vocabulary that follows a few consistent spelling rules is an example of this concept, as are physics lessons that begin with consideration of a homogeneous frictionless environment.

Teaching disadvantaged children a miniature language that someone else has made up for them may sound a bit 1984-ish to the doubters among us. However, it should be noted that the principle of starting with a miniature system, which is part of but more easily grasped than the entire system, is a respectable and widely used pedagogical device. Reading instruction that begins with a limited vocabulary that follows a few consistent spelling rules is an example of this concept, as are physics lessons that begin with consideration of a homogeneous frictionless environment.

These ideas about language learning were adjusted to making claims about learning and cognition among human children and were met with a variety of objections. Because they were influential to our work, in what follows we concentrate on the ideas that emphasized the culturally situated nature of language use and its acquisition.

Cultural Difference, Not Cognitive Deficit

Linguistically sophisticated social scientists in the U.S. spearheaded the emblematic attack on the cultural deficit perspective, including the ways it mobilized a specious view of language. William Labov, a linguist who studied social class and ethnic/racial variations in language use, appeared as an articulate and influential spokesperson. Others include Roger Shuy, Walt Worfram, Ralph Fasold, and William Stewart (see Baratz and Shuy, 1968).

In 1970, Labov published data undermining the application of standardized tests of linguistic ability to poor Black children. He claimed that the low scores of children who spoke non-standard (Black/African-American) English on standardized language competence tests arise from the inadequacies of the testing, not from the inadequacies of the children. To demonstrate his point Labov arranged for a comparison of the language used by an eight-year-old boy, Leon, in three settings: a standardized test, a less formal test conducted by a local resident in the child’s home, and a far less formal interaction involving Leon and a friend in which the adult test administrator provoked the boys to speak.

Labov drew two major conclusions from his observations. First, he asserted that what applied to his test-like situation (derived from the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities) applied to IQ and reading tests as well: they would underestimate such children’s verbal abilities. Second, he insisted that the social situation is the most important determinant of verbal behavior. By extension, he argued that adults who want to assess children’s capacities must enter into the right kind of social relation in order to find out what the child is capable of doing.

Labov’s critiques resonated with many social scientists on both narrowly scientific and more general ideological grounds. By 1970, many were ready to move away from the language of a “cultural deficit” model, and they placed their bets instead on a model of “cultural difference.” Underlying this shift, scholars seemed to believe that it was possible to organize institutional settings (preschools) in such a way that curricula could provide an “antidote” to a culturally deprived status. Everything was up for grabs: how cultural deprivation was formulated by common sense, how it was described and diagnosed by social scientists, and how it was mediated and maintained by social policy. However, the underlying belief that change was possible remained intact.

The Initial Problematic of LCHC: Academic and Practical Challenges

The intellectual rationale for the founding of the research laboratory grew in response to the controversies surrounding ideas of culture of poverty, a belief in the centrality of early experience on later intellectual development, and a confidence in the pedagogical theories growing out of American learning theory.

The Liberian research had shown that, at a minimum, standard experimental procedures and tests imported from outside a given cultural group are inappropriate for generalizing claims about intellectual ability. It had also shed doubt on the potential effectiveness of standard formal educational procedures to close academic achievement gaps. Both of these lessons had been seriously neglected in domestic research in the U.S. It seemed only common sense to us at the time that the logic that applied in Liberia could apply on the others side of the Atlantic.

Assuming the right social conditions could be created, the stage seemed set for domestic, comparative research that focused on the role that social science might be playing in creating exactly those social inequalities that it was certified to alleviate. The operative word is “assuming.” As the history of science reminds us, it can be a non-trivial task to create the conditions needed to make observations relevant to a scientific theory. And, it can be an even more daunting task to take insights gathered from research with Petri dishes, antibiotics, farm machines, or neutron bombs. Over and above good intellectual reasons to continue pursuing issues of culture and development begun in Liberia, there were also serious socio-political issues that had to be confronted before such an effort could be seriously undertaken.

One of the key assumptions of work in Liberia was that in order to understand how culture influences the mind, it is necessary to investigate those areas of experience where cultures provide people with dense practice. This meant that we had to look at people’s everyday experiences in contexts of importance to them. In Liberia, we had only approximated such conditions, and we were acutely conscious of the shortcomings of our own efforts. Local students who had achieved the rare heights of college education, combined with the hospitality and curiosity of local villagers, mediated what little we knew of local cultural life. Our efforts were also implicitly backed by the authority of the government that sponsored our presence in their homelands and by the money associated with the presence of Americans in the poor countries of the world.

Achieving access to people’s everyday lives in this limited sense was a great benefit to the work, but it came at a high cost. We could accompany people to their work sites and sit around asking questions or posing various puzzles, but we were unalterably foreign. We needed expert help from people who understood from the inside how things worked in order to keep us from blundering into trivia. Our most effective helpers were high school and college students, young people (mostly men) who had one foot in the world of Western schooling, but retained a local knowledge of how things work outside of school.

As time went by, we came to understand that our helpers were often marginal people. Only rarely did we find someone who had advanced into relatively select circles of indigenous knowledge as well as into the culture of the school and modern life. Nonetheless we had entry, and we sought to work out ways to teach about what we were doing in exchange for what we learned.

In making the transition to New York City in 1969-1970, an entirely new set of problems had to be faced. Paramount among these was cooperation from local minority scholars who could provide insider knowledge of everyday cultural practices in their own communities. When Cole first began to explore the possibility comparative research within the U.S., he contacted Dean A. J. Franklin who was faculty at Medgar Evers College, a heavily minority institution within the City University of New York. Together they discussed whether there was any way in which black and white researchers could collaborate on research relating cultural variables to cognitive development. Although there were major doubts, Franklin read about the Liberian research and continued talking to Cole and to his colleagues at Medgar Evers College.

Finding a route to mutually beneficial collaborative research was a difficult task. African American leaders were leery of white researchers taking responsibility for research on the chance that it might be helpful in combating the oppressive forces of racism in American society. They were, of course, both right and wrong. As were we. There was great progress to be made. Important progress, as we shall see, but mainstream psychology could not deliver what was needed then, and only a little better situated now.

Finding a route to mutually beneficial collaborative research was a difficult task. African American leaders were leery of white researchers taking responsibility for research on the chance that it might be helpful in combating the oppressive forces of racism in American society. They were, of course, both right and wrong. As were we. There was great progress to be made. Important progress, as we shall see, but mainstream psychology could not deliver what was needed then, and only a little better situated now.

In his discussions with local African American colleagues, Cole argued that he could be seen as a “technician,” not a “colonizer” –– that is, an experimental, cross-cultural psychologist who knew how to do alternative kinds of research. That research could not be done alone, but it could be done in cooperation with people who had complementary and necessarily specialized knowledge that was one part of the solution to a common problem. In this case, the problematic was to better understand the relationships of culture and cognition in their historical and social contexts as a resource for addressing the very real problems of social inequality. Black scholars, on the other hand, wanted to formulate a Black psychology that was rooted in their historical experience in an effort to try to deal with their predicament in America and the world.

The promise of the Liberian research was that, if properly organized, collaboration could produce the principles of a cultural psychology, of which Black psychology could provide one example. Over time and to some degree, this argument prevailed. More than at any time since, there was constant pressure to orient psychological research not just to social problems, but also to the ways that various groups, both mainstream and disenfranchised, understood the problems.

There was a second serious problem. Even if it proved possible to forge a coalition with minority group scholars, what was the institutional feasibility of the work we were proposing? Just what could we promise? For an early discussion of these issues, see Cole & Bruner, 1971.

Then, as now, the vast majority of research on cognitive development took place in highly constrained social situations such as those confronting Leon in the episodes taken from Labov’s work. How could we start the process of psychological analysis from prior knowledge of the everyday activities outside of state-scripted institutional activities? Like the problem of inter-ethnic scholarly collaboration, the problem for everyone involved was how to connect the research with the everyday activities of people in an intellectually responsible way. For better and for worse, the decision was made to see if a program of comparative cognitive research, following the logic and the spirit of the Liberian research, could be organized. Cole remained at Rockefeller University and LCHC began to take shape. This history is charted in the following section: The Rockefeller Years.

Chapter Two Compositors: Michael Cole, Joe Glick, Lois Holzman, Ray McDermott

Chapter Two References and Additional Resources

Back to Section One Introduction and Chapter One

Forward to Section Two Introduction