It is difficult to overstate the overall impact of the 5th Dimension (5thD) experiment on the subsequent directions of the Lab’s research. Over the next two decades, a combination of factors expanded the initial 5thD project far beyond the limited set of settings we had envisioned as an object of research in our initial plans. It was by no means the only line of research carried on by LCHC members, but it inspired and supported other lines of research, as later chapters will describe.

Several factors seemed to feed on each other, collectively contributing to what was, for us, a torrent of interest and activity around the 5thD. Among these were pragmatic and theoretical interests, including the mania over the apparent potential of digital computers to transform education, the social crisis arising from the erosion of affirmative action programs, a sudden interest in new forms of outreach from universities to their surrounding communities, and an upsurge of interest in our approach to designing activities for the after-school hours. Whatever the set of circumstances, interest by many colleagues and institutions provided us with unprecedented opportunities to push the boundaries of our initial ideas about designing “same tasks (5thDs) in different institutional settings” (see Chapter 6). In this case, it was not psychological tests that constituted the tasks, but the many varieties of 5thD programs placed in different settings in order better to understand the conditions of successful programs (even as we had to watch some fail). At the same time, we were able to trace how they were transformed by and/or transformative of their local environments during their lifetimes.

In this chapter, we summarize the main lines of research that grew out of the initial 5thD design experiment described in Chapter 11. To the extent possible, original materials are located on the Projects Page.

The Distributed Literacy Consortium

At the end of the first full-blown experiment with the 5thD described in Chapter 11, a plethora of questions arose. The activities really did seem promising. New sites were started spontaneously as people heard about what we were doing and wanted to know how to get in on the action. Conscious of the difficulties we faced at UCSD sustaining such a program, we wanted to know what sorts of universities, university departments, and community organizations might create the most favorable conditions for building lasting programs. Were these 5thDs having any positive effects for the students and community organizations in poor neighborhoods?

The first expanded effort to address such questions came in the form of a project entitled “Capitalizing on Diversity, a Proposal for the Distributed Literacy Consortium,” which was supported by a Mellon Foundation program focused on promoting literacy. The project included a team of researchers from five different of institutions of higher learning in five geographical locals who partnered with a total of six community organizations in widely distributed parts of the US. This core team was complemented by teams of researchers with special expertise in evaluation.[1]

Evaluation of voluntary after-school programs is a tricky business. First, what do you use for control groups? What should one be testing for? How can one document processes of learning and development in a manner that addresses ongoing controversies about processes with many policy implications? To take on these tasks, three “evaluation teams” conducted the evaluation work. A “Language and Culture” group focused particularly on sites that were located in neighborhoods with lots of English Language Learners. A “Cognitive Evaluation” team focused on creating useful measures of performance, experiments, and quasi-experiments, as conditions allowed at the different sites. A “Process” team focused on documenting actual processes of teaching and learning as they occurred in those settings where we could arrange the conditions to audio and video record effectively.

Because the idea was to create dense enough interaction among the different implementers that they could effectively help each other, the consortium, which operated between 1991 and 1996, constituted itself as what we subsequently referred to as a “Co-laboratory.” Using the still-nascent potential of the emerging Internet, we instituted a norm of reporting weekly on an email listserv about the doings of the day, the problems encountered, and the insights gained. We also created a staff position for a person whose major job was to promote discussion on the Internet and chase after people too caught up in local affairs to find time for writing updates. Although not entirely effective, these measures produced a steady stream of participant accounts of their projects over time. The listserv was also used to cook up joint projects that provoked children at different sites to communicate with each other. In those earliest days of the Internet, these simple organizational practices were still an anomaly.

The second major focus of the consortium was to identify the common characteristics of various 5thD sites, a topic that was visited and revisited repeatedly. By the mid-1990s, various formulations had converged on a minimal set of principles that were couched in the roughly the following terms:

- A 5thD is a joint project between a university/college and a community institution. The university provides supervised undergraduates to the community institution as labor while the community institution provides necessary space, equipment, and supervision of the activities to provide the students with a valuable research experience.

- The activity includes a mixture of “leading activities” including affiliation, play, learning, and work as multiple sources of motivation for participation.

- Participation structures for small group interactions are designed to minimize power differentials between the participants, particularly the undergraduates and the children with whom they work.

- Heavy emphasis is placed upon the value of communication in a variety of media, including computers, conversation, and writing in the service of meeting goals that are provided within the activity setting.

- Participation by children in the activity is voluntary. Children are free to leave at any time. Consequently, the games and other activities that participants engage in must adhere to goals that the children find interesting.

The Mellon-sponsored project lasted for 6 years, an unusually long period to be allowed to conduct social science research of this interdisciplinary, labor-intensive form. A large number of research reports and eventually a book documenting the successes and challenges of such activities were produced. These can be found on the Projects Page.

As support from the Mellon Foundation was coming to an end, political events in California directly affecting the University propelled the 5thD to a new level of activity, stretching it well beyond its initial focus on elementary school children and desk top computers. This stretching expanded enormously the range and institutions activities that our university-community collaboration could productively engage in.

The Birth of University-Community Links (UCLinks)

In the summer of 1995, the Regents of the University of California made a controversial change in statewide admissions policies. In a special resolution, they declared that, “Effective January 1, 1997, the University of California shall not use race, religion, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin as criteria for admission to the University or to any program of study.”

There were a variety of University programs that sought to encourage minority student enrollment through informational outreach as well as some local and regional research units that were devoted to the study of barriers to educational achievement among ethnic minorities in poor, underserved neighborhoods. Nevertheless, this legal decision left the University with no plausible mechanism for addressing the obvious and continuing inequities in educational access that characterized California’s educational system.

The time seemed right to offer the overall 5thD model system as a pro-active measure for our colleagues at various University of California campuses who shared our concerns about equity and our interest in community-based, university collaborations involving after-school activities. The case seemed a strong one because it offered a publicly visible way of demonstrating faculty commitment to the three-fold mission in the charter of the University of California as a public institution: to combine research, teaching, and community service.

The President of the University at the time was Richard Atkinson, who had just been promoted to the Presidency of UC from his position as Chancellor at UCSD. He knew of the 5thD program and its involvement of UCSD students and faculty in local under-represented communities. Confronted with the Regents’ rejection of affirmative action, he needed to demonstrate that the University had a commitment to equity and diversity despite legal restrictions on how that commitment could be implemented.

Atkinson provided seed money to permit Cole and Olga Vasquez, the designer of La Clase Mágica and a central member of the Mellon project, to visit faculty across the UC system who might be interested in a state-wide effort to adapt the UCSD models and implement programs as at least the start of a response to the Regents’ new policies. Charles Underwood, an anthropologist specializing in faculty and community engagement issues in university-community collaboration, traveled with Cole and Vasquez to help formulate a workable plan. They found support for the idea from scholars located in various departments on all nine campuses of the University.

Even as plans were being made to implement UCLinks programs across the UC system, the situation with respect to affirmative action programs became more acute. During the 1996 election, California voters amended the California Constitution through an initiative known as Proposition 209, or the “California Civil Rights Initiative.” The proposition included the following crucial section “The State shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.”

With new anti-Affirmative Action policies already being planned and implemented, the newly formed UC Links Project was quickly elaborated into a statewide program to be initiated in the fall of 1996. Cole, Vasquez, Underwood, and several faculty crafted a multi-campus proposal for a statewide 5thD-type initiative and submitted it to President Atkinson, who approved and funded it provisionally for two years. It was then permanently funded after having been scrutinized.

The UC Links program exists to the present day. It grew from 14 sites in the 1996–1997 academic school year to 28 sites in the 2016-2017. Since its initiation, UC Links has engaged over 35,000 youth in diverse communities across the State of California as well as approximately 12,000 undergraduates from UC campuses as well as from a number of Links programs that sprouted up in the California State University and Community College systems. UC Links continues to play a prominent role in fostering the growth and sustainability of the network of programs in California through the allocation of consistent core funding and the forging of a distributed network of programs. Through its efforts, the community and university partners of these programs are continually aware of, learning from, and at times linking with each other’s work across geographical, cultural and linguistic borders. Through its key role in establishing UC Links, LCHC is proud to have served as a catalyst for the sustained growth of these programs.

Continued Local and International Expansion of the 5th Dimension Project

Throughout the 1990s and continuing to the present day, institutions in the US and around the world have created activities modeled in various ways on the 5thD. These re-designs vastly increased the range of sociocultural ecologies within which it has been implemented (see Communication in Context: A Case Study of Simon in the Classroom and the Fifth Dimension by Anne Eckles, 1999). Early on, Berthel Sutter at the Blekinge School of Technology in southern Sweden was interested in using the 5thD model to prepare undergraduate students to be software designers. Monica Nilsson, a colleague of Berthel’s, started a 5thD as a means of studying ways to transform and develop school structures and activities.

More…

Projects inspired by the 5thD model sprouted up in several locations in Spain, Mexico and Brazil. They had varied emphases. Some focused on technological skills, some on literacy, some on play as a foundation for later education, some on preschoolers, some on high school youth, some on inclusion of Gypsies in their local community, some living and working on street of Sao Paulo, and some for children with perinatal stroke and early traumatic brain injury. All involved a focus on bicultural inclusion and mutual respect.

The convergence of events that lead to the expansion of university-community programs that took their inspiration from the 5thD seemed to hit its zenith in the late 1990s. This expansion occurred not only locally in the San Diego area or regionally in connection with UCLinks, but also nationally and internationally as a result of collaborative projects in different parts of the US and Europe. A major common goal was to explore what the advent of the new digital media portended for the organization of teaching and learning.

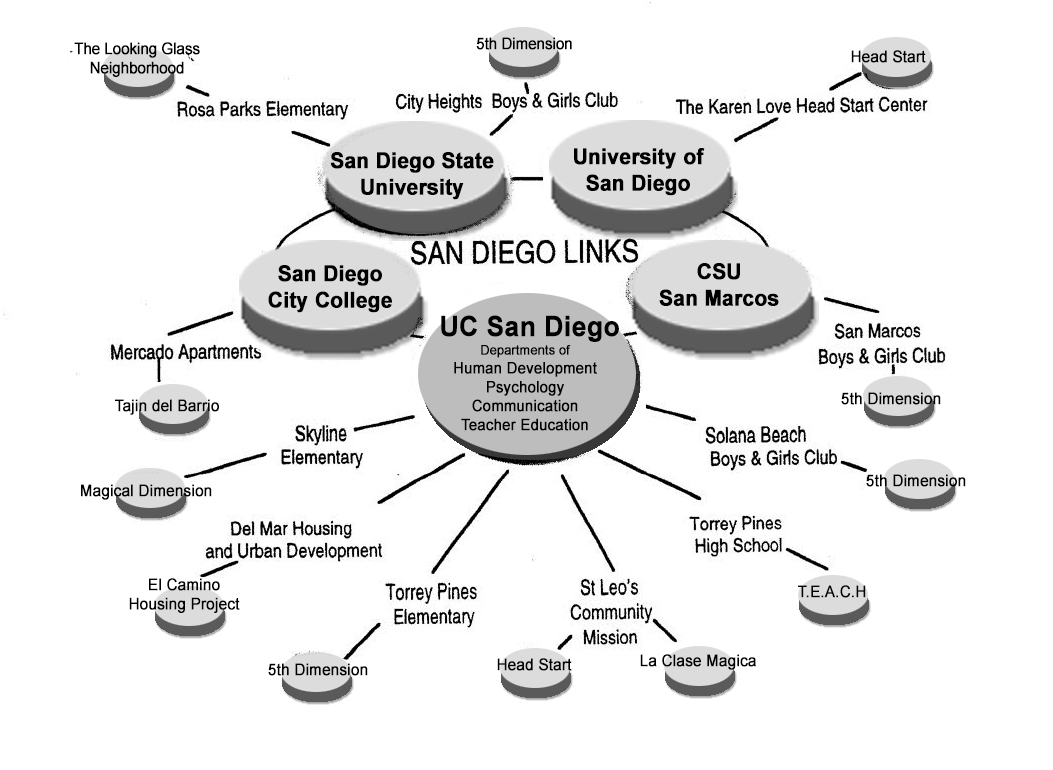

The diagrams below give some idea of the scope of these activities in 1998. The first is a figure mapping 5thD-inspired, university-community links programs in San Diego County, all of them connected in some way with LCHC. Examination of the diagram will show a patchwork of connections, with LCHC and La Clase Mágica at its core, radiating into neighborhoods throughout the San Diego region. Components ranged from the University to Community Colleges and from programs reaching from pre-school through high school.

UC Links in San Diego region

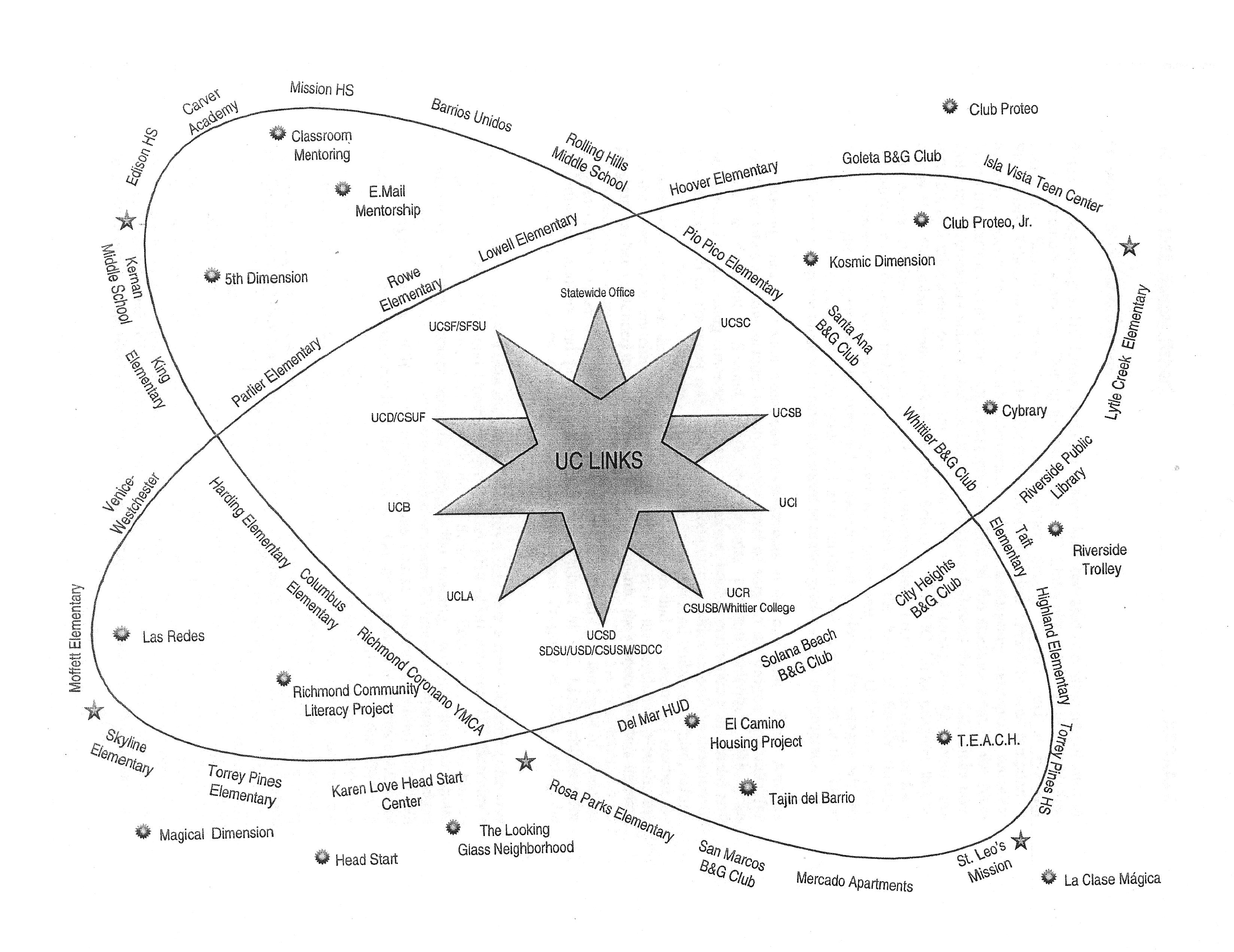

The second diagram provides an analogous description of the program of activities, as interpreted by the UC Links statewide office, now located in the Graduate School of Education at UC Berkeley.

This crazy quilt of activities indicates the kinds of hopes that the UC Links/5thD programs engendered in a broad range of sociocultural ecologies. The variety of arrangements was far beyond anything we could have conceived of at the outset before. Each University-Community system involved some sort of programming that brought undergraduates and children/youth/community adults together in some configuration. All made heavy use of email for documenting their activities and educating the undergraduates, while assisting the local participants to become familiar with contemporary skills necessary to be a skilled computer user for a variety of purposes.

Building on LCHC’s early experience using video to link distant sites in joint activities, researchers in the various partnerships conducted two-way television classes between university courses so that students in the different systems could compare notes and learn from each other’s experiences (For more information, see the report on the UCSD/UCLA Distance Learning Project of 1996/1997). A program was begun that linked LCHC instructors to community college courses where UC Links programs were co-taught as part of an effort by UC’s central administration to ease the pathway from two year to four year colleges.

Simultaneously, there was a growing desire to experiment with new kinds of activities as digital technologies continued to evolve rapidly. Wherever possible, these explorations took place as part of an already-present after-school activity center with a 5thD-like program.

The Demise of the local BGC Fifth Dimension and a Period of Exile

There are many published accounts of the history of the Boys and Girls Club (BG Club) 5thD (see Chapter 11 and 5th Dimension Projects Page). The BG Club was the sole survivor of the first foray into the study of designing, implementing and sustaining such activity systems. In 2005, the program, from an LCHC perspective, was running as close to ideally as we had experienced in our 16 years with the Club. However, the BG Club decided to close for two years for a makeover that would convert it into an aquatic center based primarily on fee-paying programs. A variety of plans were discussed for continuing the 5thD in temporary headquarters during the makeover, but in the end, the decision was to close the club and provide busing to another Club about 5 miles down the freeway.

At first, it seemed that moving to the new Club was an obvious next step for the 5thD. The director at the new BG Club site was a former director at the 5thD’s home Club and was excited about moving the program down to his new branch. A concerted effort was made to implement a 5thD, modified to fit the routines and culture of the new club. However, it quickly foundered. A number of factors were at work. The leadership of the regional clubs had changed, and the new leaders were less familiar with, and less in tune with, the objectives of the program than their predecessors had been in prior years. We had crossed an institutional changing of generations at the BG Club organization. A part of this change was a clash of cultures between UCSD and local Club leadership. This clash displayed itself in the demand that all UCSD undergraduates undergo an FBI check in addition to vaccinations in order to interact with the children. This was not a national policy, nor was it a widespread policy among the Clubs in the area. This demand was accompanied by a proscription of tattoos or body piercing among the UCSD students as well as the Club’s staff. Moreover, the Club staff preferred a command and control approach to organizing after school activities that was antithetical to LCHC’s approach.

Having already signed up UCSD undergraduates for the winter quarter well before the end of the fall quarter, we prepared to cancel the class and call it quits. However, a new opportunity presented itself in the form of La Clase Mágica. Olga Vasquez, who had struck out on her own to enlarge the bilingual/bicultural focus of the 5thD, found her project in a quandary about how to maintain their existing systems. The LCHC group suggested that we run La Clase Mágica while she sorted out what she wanted to do next. Such an arrangement worked well for Olga, as she worked on building the infrastructure for the expansion of the La Classe Mágica programming. Thus began a year and a half of delightful research on the organization of after-school activities in the Latino area of the town that housed the BG Club. Here were the children we did not get to see afterschool in prior years, in their neighborhood.

Acutely aware that we were Anglos, guest-refugees looking for a place to conduct our research, the program at La Clase Mágica was, by all measures, a successful one. We had ample help from El Maga, La Clase Mágica’s analogue to the Wizard-ess. Spanish mixed with English, Japanese, Thai, Vietnamese, Cantonese, and Russian as a mixture of visitors, old time La Clase Mágica families, and new community-based staff put together a program that had a big impact on everyone involved. An idea of the spirit of this enterprise is best obtained from viewing the brief video about La Clase Mágica produced in 2006.

However, over time it was clear that realizing the full potential of this La Clase Mágica required that it be properly integrated into the broader La Clase Mágica Project. It was time for us to go. And as fate, or perhaps the Wizard would have it, we had a place that was anxious to have us around. In the spring of 2007, we bid goodbye to the 5thD, and we joined the ranks of UCLinks using a new way of forming university-community partnerships, which we came to refer to as a process of mutual appropriation.

Chapter Twelve Compositors: Mike Cole and Charles Underwood

[1] The partners were: UCSD/LCHC (Cole & Vasquez), working with a BG Club and the bilingual bicultural site, located in two ethnically distinct neighborhoods in the same costal suburban community near UCSD; CSU San Marcos, (Pat Worden and Miriam Schustack) working with another local BG Club site in North County San Diego; Michigan State University (Margaret Gallego) working with a community site also called La Clase Mágica East at a local community center; Appalachian State University in North Carolina (Bill Blanton) and various school locations; UC Santa Barbara (Richard Duran and Betsey Brenner) and Whittier College (Don Bremme), two different kinds of institutions of higher learning partnered with local BG Clubs in two different California cities.

Back to Chapter Eleven

Forward to Chapter Thirteen