Culture, Development, and Schooling: Literacy in Liberia and the Yucatan

As noted earlier, research conditions at Rockefeller University made it possible conduct international cross-cultural work that followed up on the research conducted in Liberia. It also enabled the development of research that used an analogous approach in the context of New York City. Because they are quite distinct in their specifics, we present these two lines of work in successive sub-sections in this chapter.

Despite their differences, their overall impulse shared the strategy of creating research methods that began on the one hand from experimental psychology and on the other hand from ethnographically grounded anthropology. Although our account is conveyed chronologically in the text, both lines of work were going on simultaneously, with a good deal of shuttling to and fro — across continents and across town.

Our subsequent investigations of the links between literacy, schooling and development pursued different paths. One focused on the schooling/cognitive development relationship by using experimental methods combined with an attempt to embed them in everyday activities developed in Liberia. The second investigated the influence of literacy (the ability to read and write a spoken language) independent of any experience of formal education. Both approaches, outlined below, were conducted with a fundamental skepticism about the measures that we typically used to address these issues.

Schooling “versus” Age in the Yucatan

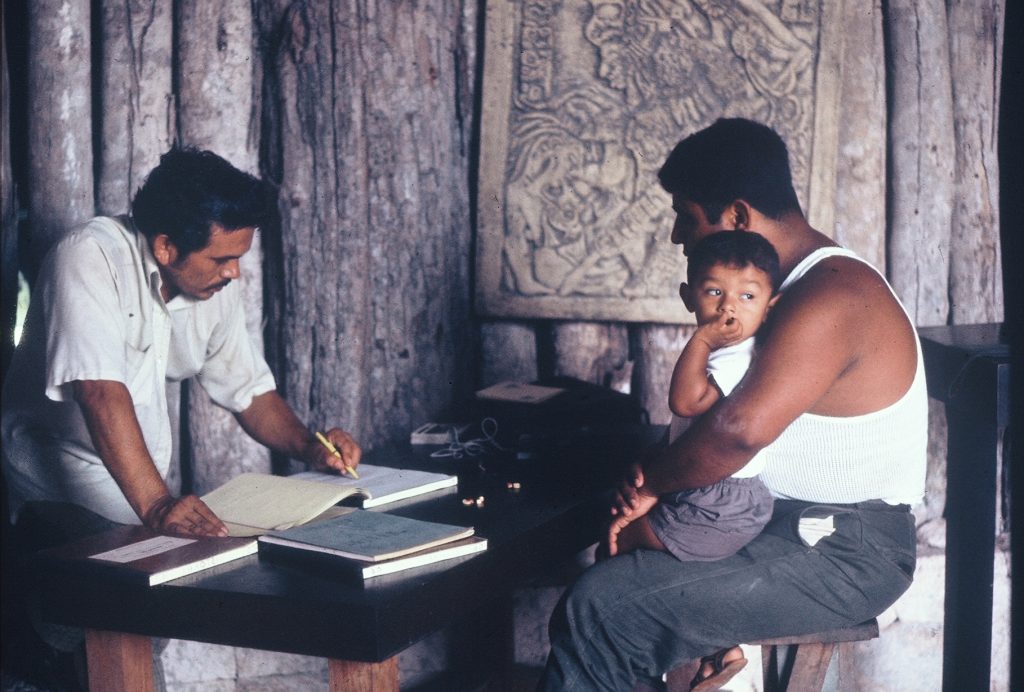

The Yucatan was the site of research by Michael Cole, Charles Lave, and Donald Sharp (see, Cole, Sharp & Lave, 1976; Sharp, Cole & Lave, 1979). The studies there were designed to follow up on the enticing findings of the Cultural Context work, which suggested that the influence of schooling on tests of cognitive development reflects the acquisition of a specific set of cognitive skills and not a general level of ability. The choice of the Yucatan as a research site was motivated, in part, by a shortcoming of Liberia as a site for research on this issue. In Liberia, schooling was too recent a development in the rural areas to generate large enough sample sizes based on a broad range of age/education indices to be investigated systematically. By contrast, schooling in the Yucatan had been present in varying amounts for many decades, offering the opportunity to study a broader spectrum of such combinations.

Following methods developed in the Liberian research, the studies in the Yucatan spanned a wide variety of classical cognitive domains that were central in ongoing debates on the consequences of schooling, including classification tasks, various kinds of memory and problem solving tasks, and the like. Considerable care was taken to insure that the language of the test, the procedures, and the stimulus materials used in the test were broadly familiar. By extension, the experiments were conducted in an informal and friendly manner by trained and supervised native Mayan/Spanish/English speakers.

The results reinforced and extended the findings obtained in our earlier school/non-school comparisons and are summarized here:

A) For cognitive tasks where the solution is based upon functional relations among problem elements, especially if those problem elements are common to everyday experience, schooled and non-schooled populations perform alike. Age comparisons in such tasks reveal that there is an increase in correct performance from childhood to adulthood (roughly, 6-20 years).

B) For cognitive tasks where the basis of solution chosen by the experimenter requires the use of taxonomic classification systems, schooled populations outperform non-schooled populations, unless the taxonomic structure of the task is made explicit.

C) For cognitive tasks where specialized information processing strategies are required for solution to the problem, schooled populations outperform non-schooled populations in ways that relate directly to the hypothetical strategy (e.g. “rehearsal”).

D) For cognitive tasks where language itself is the topic, non-schooled populations are more likely than schooled populations to treat the answers to hypothetical reasoning questions as matters of empirical fact.

Daniel Wagner similarly carried out a carefully executed study of the role of schooling in the development of short-term memory, which supported the conclusion that a general change in basic cognitive abilities is linked to schooling rather than maturation. Finding that performance on a widely used memory task increased entirely as a function of years at school, not chronological age, Wagner (1974) concluded that without formal schooling, “higher mnemonic strategies” might not develop at all.

So long as one believes in the validity of the psychological tasks as indices of a general cognitive ability, these data appeared strongly to support the idea that schooling is central to increasing the cognitive performance reported in standard textbooks, and not age or maturation, per se. The crucial question for us, then, became whether the measured abilities were specific to school-like tasks or whether they reflected a general change in cognitive dispositions.

Cognition arising in the domain of everyday life

Another interpretation, which echoed the various doubts engendered by our prior cross-cultural research, was that the results were a kind of mirage of overgeneralization. Here is how we posed the problem at the time:

“It is perhaps easier to see how strong our assumptions about test performance and cognitive development really are if we consider some examples from very different domains of behavior. Suppose, for example, that we wanted to assess the consequences of learning to be a carpenter. Sawing and hammering are instances of sensorimotor coordination. Learning to measure, to mitre corners, and to build vertical walls requires mastery of a host of intellectual skills that must be coordinated with each other and with sensorimotor skills to produce a useful product (we are sensitive to this example owing to our own lack of success as carpenters!). To be sure, we would be willing to certify a master carpenter as someone who had mastered carpentering skills, but how strong would be our claim for the generality of this outcome? Would we want to predict that the measurement and motor skills learned by the carpenter make him a skilled electrician or a ballet dancer, let alone a person with ‘more highly developed’ sensorimotor and measurement skills?” (Cole, Sharp, & Lave, 1976, p. 227).

There is no need to go more deeply into these issues here; they will be returned to again and again in this narrative. However, they should be kept in mind as we encounter the domestic side of the research program of LCHC because they point to a key logical problem in the entire enterprise of comparing schooled and non-schooled people with respect to their cognitive abilities, modes of thought, and other such notions. This problem echoes the problem of comparative, cross-cultural research more generally. In brief, the problem is the following: In order to compare the ways schooled and non-schooled people think, it seems necessary to present each group with learning challenges about which they have equal knowledge to begin with. This requirement is a simple extension of the problem of using equally familiar stimuli.

Such a “common” task cannot be a problem that is representative only of the experience of people with schooling. It most decidedly should not mimic the domain of schooling. Rather, it should be a problem arising in the everyday life of the village. Alternatively, one might try to find a task that is equally unfamiliar to schooled and non-schooled people alike. Here we have the idealized notion of a “culture free” cognitive task that continues to animate scholarly attention. Nevertheless, the process of inquiry as a discursive practice carries with it cultural pre-suppositions of the highly educated. Insofar as we could imagine consequences, they seemed to be related to the kinds of changes in values that occur for people who became educated, including changes in their ability to navigate the governmental institutions (e.g., the health care system) that might be long lasting effects of schooling. That supposition was born out many years later in work conducted by Robert LeVine and his colleagues (see also, the introduction to LeVine et al., 2012 by Mike Cole).

At this point, we were left with deep concerns about the entire technology of cognitive psychological analysis as it was institutionalized in the relevant disciplines of the 1970s. Fortunately, as the work in the Yucatan was coming to an end, a new project in Liberia provided a different avenue through which to develop a methodology we could put more faith in.

Literacy without schooling: The Vai

Scholars have often posited literacy as the great invention of human history that transformed mental function–underpinning the accumulation of systematic knowledge, the transformation of human thought, and the development of civilization. Institutionalized in schools, literacy has been identified as the engine that produces the cognitive and social consequences attributed to involvement in schooling. But what about literacy “itself,” the ability to read and write a system of inscription representing oral speech?

Scholars have often posited literacy as the great invention of human history that transformed mental function–underpinning the accumulation of systematic knowledge, the transformation of human thought, and the development of civilization. Institutionalized in schools, literacy has been identified as the engine that produces the cognitive and social consequences attributed to involvement in schooling. But what about literacy “itself,” the ability to read and write a system of inscription representing oral speech?

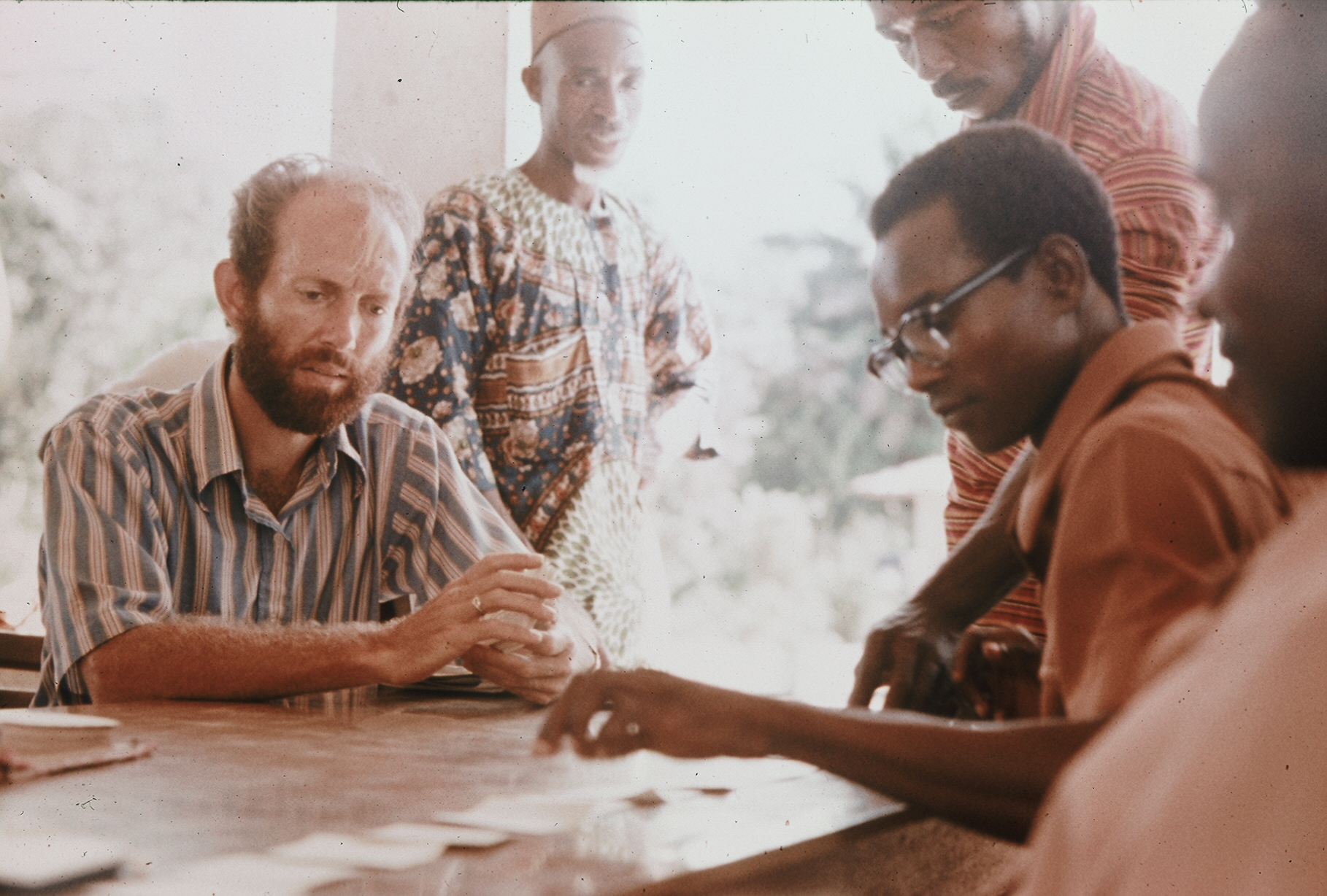

In the early 1970s, Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole received support to study the developmental/psychological consequences of literacy and schooling among the Vai, a tribal group residing along the northwest coast of Liberia bordering on Sierra Leone. The Vai had first caught their attention while working on the Cultural Context Project because they had been using a writing system of their own invention for more than 100 years but had no system of formal schooling. The Vai seemed to provide a rare “experiment of nature” in which literacy and schooling, so tightly bound up in almost every society in the world, could be teased apart as factors in social and cognitive change.

Ethnography and initial field research

The Vai research was carried out in three overlapping phases. First, the research team conducted an ethnographic study and an extensive survey of the social correlates of literacy and schooling. This phase was conducted in recognition that the research team needed to have some idea of how literacy was interwoven with life experiences among the Vai. That is, even if literacy was not fused with schooling, they presumed that it was likely associated with other life experiences that could plausibly account for the development of cognitive abilities. As part of this sociological survey, the research team added a battery of psychological tests that had been used to assess the cognitive consequences of schooling in earlier research. These initial inquiries sought to answer the most straightforward question one might pose: does Vai literacy substitute for schooling in producing improved cognitive performance on learning, classification, and problem solving tasks?

Different forms of literacy in the Vai

From this preparatory research, Scribner and Cole found three kinds of literacy among the Vai: about 20% were literate in Vai, 16% had some degree of literacy in Arabic (mostly, but not entirely, to read from the Qur’an) and about 6% were literate in English, which they had acquired in school. Neither Vai nor Qur’anic literacy substituted for schooling with respect to standard psychological test performance. In general, however, those who had been to school performed better on the tests, especially when asked to explain the basis of their performance.

The survey and parallel ethnographic observations indicated that, unlike literacy acquired in school, Vai literacy involved no mastery of a body of esoteric knowledge or new forms of institutionalized social interaction. There was no tradition of text production for mass distribution, nor were there traditional occupations that required literacy. Further, Vai literacy did not prepare the learner for a variety of new kinds of economic and social activity in the modern economic and governmental sectors. Rather, learning almost always occurred as a matter of personal interest and was carried out in the course of daily activities –most often, when a friend or relative agreed to teach the learner to read and write letters.

At the same time, Vai literacy skills clearly played a useful role in traditional occupations as a means of keeping records about family matters or business transactions. Especially widespread was the practice of writing letters to relatives living in different parts of the country, which were exchanged through the ubiquitous taxicabs that plied the Liberian countryside.

Metalinguistic survey

Metalinguistic survey

In a second round of experimental research, the focus narrowed to test the widespread notion that practice in reading and writing changes a person’s understanding of the properties of language itself. The tasks in this “metalinguistic survey” included the ability to define words, engage in syllogistic reasoning, distinguish between an object and its name, make judgments about the grammaticality of various utterances, and explain what was wrong in the case of ungrammatical utterances.

There was no support for the notion that literacy promotes meta-cognitive awareness in general. The only one of these tasks that consistently yielded a positive influence of Vai literacy was the ability to make correct judgments about source of difficulties in ungrammatical spoken phrases. In seeking an explanation for this “outlier” result, a plausible explanation was suggested by observations of Vai literates discussing letters that they received or were in the process of writing. Such activities often involved discussions of whether phrases contained in a letter were written in “proper” Vai.

These exchanges suggested that it was plausible to attribute Vai literates’ skill in grammatical judgments to their practices when writing and reading letters.

Tracing cognitive change to cultural practices

The next challenge suggested by the metalinguistic survey was to extend the range of tasks that sampled actual practices of literacy derived from the accumulated ethnographic observations that were a part of the research team’s activities from the very beginning. For example, the research team analyzed a large corpus of letters they had collected. They found that while the contents were likely to be relatively routine (and hence easy to interpret), the letters nonetheless contained various “context setting” devices that accounted for the fact that the reader was not in face-to-face contact with the writer in a shared setting.

The research team speculated that extended practice in letter writing might promote a tendency to provide fuller descriptions of local events needed for interpretation by someone at a distance. They tested this notion by creating a simple board game that was similar to games common in the area, but different enough to require explicit instructions. Vai literate and non-literate people were asked to learn the game and dictate a letter to someone in another village in enough detail for that person to be able to play the game based on the written instructions alone. Consistent with expectations, Vai literates were far better at this task than non-literates. Importantly, among Vai literates, a person’s degree of experience in reading/writing was positively associated with setting a context when explaining the game.

Following this path of analyzing specific practices, the research team found a variety of effects of Vai literacy. Notably, Vai literates were better able to fulfill rebus-like tasks that required people to integrate information from pictures and transform their sounds appropriately to come up with a meaningful new word or phrase. For example, the word for chicken (ti-ye) and the word for paddle (laa) when combined yield the word, “waterside.” The person is shown the pictures of the chicken and paddle and asked, “What place is this?”

Overall, Vai literates were highly proficient at this task, although even non-literate Vai people were able to read the pictured phrases, and interpret them in terms of oral language in order to answer this question roughly 50% of the time. Detailed analysis of the data indicated that Vai literates were especially good at interpreting sentences that required several sound transformations, whereas these sentences were very difficult for non-literates. The research team obtained very similar results when people were given a set of pictures and asked to “write” a sentence by laying out the pictures in a sequence. Engagement in Vai literacy practices promoted quite specific, relevant, psychological skills.

When Scribner and Cole brought together all of their results, a consistent pattern appeared: the more closely a given cognitive task fit the actual practice of using the written language, the more clearly the influence of that practice showed up in the test results. By locating the process of cognitive change in cultural practice and by applying this principle to the practices of schooling Scribner and Cole approached a balance between analysis of everyday practices and the design of experimental methods that their earlier research had been striving for. From this perspective, experiments were treated as models of indigenous practices, not as context-free indices of hypothetical psychological abilities.

This shift in focus also suggested a different way to think about the issue of “general” versus “specific” changes in cognition. It became possible to link the generality of the consequences of literacy to the pervasiveness and nature of cultural practices using literacy in a given society.

Domestic “cross-cultural research”: A focus on ethnicity and social class

The initial research studies conducted in New York City took their shared focus from the debate between the difference and deficit theorists discussed in Chapter Two. On the one hand, they oriented to research using memory and classification tasks that figured in the Liberia research and the data upon which cultural deprivation theorists relied. On the other hand, they faced the problematic of breaking out of the school into everyday life, while somehow remaining within the analytic orbit of psychology. This began the long process of gathering data about language use and problem solving in the lives of children in their homes as well as in their schools.

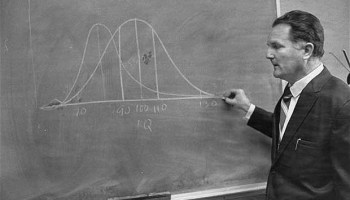

Following the memory and classification trail

A focus on studies that combined modes of classification with modes of remembering was one line of research that was relatively easy to initiate that would speak to Arthur Jensen’s claims about the difference in modes of learning that were characteristic of African American populations. A key issue in Jensen’s studies was that of basic levels of memory development. Level I, or associative learning, was defined as retention of input and rote memorization of simple facts and skills. Level I was seen as an elementary (or “natural”) form in which new experiences are simply incorporated into memory associatively. Meanwhile, Level II was defined as the ability to manipulate and transform inputs. Level II marked a higher-level form of conceptual learning that requires active transformation of the incoming information in order to retain it and to use it more effectively in later instances.

Jensen followed the standard procedure of using published vocabulary frequency norms to create his experimental materials. This was a purposive choice by Jensen, who assumed that he was obtaining culturally equivalent stimuli and thus a “fair test.” However, our cross-cultural research had made us deeply suspicious of such claims. So it was only natural to redo some of the standard experiments, taking special care to make certain that the words being used to test for higher-level conceptual learning were in fact equivalent among different socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

Jensen followed the standard procedure of using published vocabulary frequency norms to create his experimental materials. This was a purposive choice by Jensen, who assumed that he was obtaining culturally equivalent stimuli and thus a “fair test.” However, our cross-cultural research had made us deeply suspicious of such claims. So it was only natural to redo some of the standard experiments, taking special care to make certain that the words being used to test for higher-level conceptual learning were in fact equivalent among different socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

A number of experiments were undertaken to examine the evidentiary base of Jensen’s claims about the differential inheritance of “higher order” intellectual abilities. These experiments could all be considered variations on the hypothesis that Jensen’s methods were flawed because he assumed equal familiarity with the materials that the children were presented. When procedures were changed to use indigenous norms, the presumed difference between ethnic groups with respect to conceptual ability disappeared.

Free recall task

Free recall offered an interesting method to use in this case because it was the kind of experimental task that Jensen used to bolster his argument, and it was a task we had studied extensively in West Africa. As used and interpreted by Jensen, the free recall task suggested that Anglo children underwent a change in the way they remember between the second and fourth grades, while Black children do not. The change in amount remembered was thought to be associated with “clustering,” or remembering groups of words together, which was taken as a measure of “conceptual organization” in recall.

The developmental difference in clustering that Jensen focused on counted as evidence of the failure of Black children to develop the underlying ability to create conceptual clusters and employ them as a tool of memory. However, Black and Anglo children did not differ when presented lists randomized in a way to make the use of a clustering strategy irrelevant.

Again, the error of this approach was that it assumed that items being used as part of the tests were from population norms that equally represented both groups. We argued, however, that they were not. Rather, they were derived from textbooks and a few corpora of spoken language that were recorded in school-like situations.

Categorization and recall

In some ways, Sylvia Scribner’s study of categorization and recall, which followed up the Cultural Context work, stands as a model for all of these studies. Scribner conducted two experiments with Liberian children, adolescents, and adults to determine the relationship between preferred mode of organization of categorizable material and use of organization in recall. She began by determining an individual’s preference for categorizing the materials they would late be ask to remember. She found that various child and adult groups differed in the types of organization they imposed on the material in a sorting task. Those exposed to school and other modernizing influences showed a preference for taxonomic organization. All of the experimental subjects, however, used their own form of organization to order their subsequent recall of the material. Cultural difference appeared to be linked to differentially organizing processes, not in the ability to conceptualize.

Very similar findings were obtained in studies of children from mixed socioeconomic schools in New York, where class differences appeared in preferred modes of organizing the materials used in the memory test, not in memory ability nor in the ability to use concepts to organize remembering.

“Indigenous” vs. unfamiliar stimuli

In some respects, the most suggestive finding in this line of work came from the work of A.J. Franklin and Lenora Fulani among Black and White adolescents. They began by collecting a set of “indigenous” stimulus materials from Black youth they encountered across a spectrum of conditions, including school, alternative schools, and local hangouts. Participants were asked to generate as many examples of a number of local categories as they could, from which drugs, types of dance, and soul food were chosen to use in a recall study. These “Black categories” were matched by three “universal categories” taken from the set of categories common to both earlier African and local research (tools, utensils, clothing). The Black students came from a school that was for poorly performing, socially problematic youth. The White students came from a parochial school. Under these circumstances, the Black students both remembered more of the items (they topped out after 5 trials), and they clustered the to-be remembered items more than the White students did.

A follow up study suggested that when the youth encountered unfamiliar, scrambled lists, their recall was disrupted. What did not appear in these studies was any reason to believe that one group or another excelled in higher-order cognitive skills involved in free recall tasks. Such a conclusion may appear bland from the long view of the present, where free recall tasks have ceased to be widely used in the manner described here. However, at the time they struck to the heart of our critique: Performance was plastic. It was dependent upon a host of factors that, when properly included in the experimental procedures, could make anyone appear to perform normally.

Dialect and Ethnicity in Story Recall

An entirely different source of previously un-inspected population differences in research on the development of remembering concerned the dialect in which the experiment was conducted. Perhaps because they did not recognize that Black children spoke a distinct dialect of English, as Labov and others insisted, no psychologist had yet taken the trouble to conduct an experiment with Black and White children comparing the use of Black English and Standard English.

A study by William Hall and his colleagues remedied that situation. Ethnic and social class variations in story recall served as the frame for a study of the relation between language dialect and recall memory. The subjects were Black and Anglo preschoolers, and the experimenters were a Black and an Anglo man. Using the careful logic of experimental psychology, half of each ethnic group was read their story and spoken to in Standard English. The other half was spoken to in what was then referred to as Black English.

All the children were told a series of stories, each illustrated by a page in a picture book. As the experimenter turned the pages, the children were asked to listen closely so that they could tell the story back after it was presented. For example, one story was about a little girl who broke a flowerpot, feared her mother would be angry, found out that her mother was not angry, and then replanted the flower. The children’s recall of the various stories was recorded.

The results showed a very marked effect on children’s recall in response to the dialect in which the story was told. Black and Anglo children recalled the same amount when a story was told in their own dialect. But performance dropped in each case when the dialect did not match their ethnicity. Clearly, no conclusions about differential “remembering ability” associated with the ethnicity of the children could be appropriate.

Non-experimental Studies of Children in Different Settings

The paucity of evidence about what actually went on outside of school (in children’s families and neighborhoods) posed a central challenge to our efforts to provide a sounder basis for understanding the sources of performance differences among children of different socioeconomic backgrounds and ethnicities. Two studies sought to provide some of the basic information.

Preschoolers Talk in the Classroom and the Supermarket

The first such line of research addressed issues raised by Labov’s work on variations in language use in different social circumstances. We particularly focused on claims that children who were thought to be virtually devoid of any language ability in standardized testing situations actually displayed impressive rhetorical skills in less formal and constrained circumstances. We wondered if those claims could be replicated in a more or less standard form that could be quantified for purposes of closer comparison. We also wondered if it was possible to create easily repeatable and culturally appropriate social circumstances in which children could be recorded as they moved between formal instructional/testing settings and informal settings of great interest to them.

This was the topic of research carried out by Gillian McNamee, William Hall, and Michael Cole. McNamee and Cole were engaged in the study of a group of children in a preschool in central Harlem, conducting different forms of play activity and observing/helping out in the classroom. They obtained permission to conduct an activity in which pairs of children from the classroom went with McNamee to the nearby supermarket, bought something to bring back to the class for a snack, and then talked about their adventures afterwards.

The results of this activity provided an interesting confirmation of Labov’s pioneering work under more constrained and quantifiable conditions. However, the scoring scheme suffered from some of the same shortcomings as Labov’s. It did not provide evidence that the constraints on talk in the two settings were equivalent –that the children, in effect, were confronting the same task in the supermarket and the classroom. The team needed an analytic apparatus to identify how the constraints on talk differ in the two settings.

The solution the researchers came up with was to use a formalism developed by John Dore, based on the idea of “communicative acts” that could be reliably identified and categorized both for adult and child utterances. The categories were based on propositional content, grammatical structure, and their function in conversation. For example, requests solicited information (“Is this an apple?”), while descriptions were statements about the properties of events, beliefs, etc. (“I saw an elephant in the zoo eat spaghetti and he ate a popcorn and some a dese”). Using these categories as scoring devices permitted a more refined way to describe, and thus compare, language use in the two settings.

A number of interesting results emerged from this work. First, as seemed obvious from the start, there was almost twice as much talking in the supermarket than in the classroom. Second, different kinds of conversational acts dominated the discourse in the two settings. In the supermarket, the children’s talk was dominated by descriptions. The children often pointed out something of interest or commented on what someone else had said. In the classroom, the children were most likely to be engaged in responding to questions from teachers. Often these were yes/no questions. But on the rare occasions that the discourse produced descriptions, those descriptions were just as long in the classroom as they were in the supermarket.

These results strongly suggested the critical effect of a change in social context on the relative frequency of different speech acts. Labov was entirely correct in his arguments that young Black children come to schools able to use language as tool of argumentation and thought, not just an emotional accompaniment to action. At the same time, these results highlight the fact that learning the discourse/cultural pattern of the classroom requires that one learn to respond effectively to the school’s demand to use the kinds of speech acts appropriate to pre-scripted teacher demands. They also mark the importance of an ability to interpret (and accept) the intentions implicit in teacher talk.

Language Use at Home and School: Ethnicity and Social Class Variations

The debates involving the role of language in the homes of the poor begged for someone to obtain a sufficiently substantial corpus of everyday speech to substantiate their claims of cultural/linguistic differences and deficits. That someone was William Hall.

With a number of colleagues, Hall collected a large sample of spoken language among 40 families with pre-school children. For this research, pre-school children were fitted with little vests that had transmitting microphones sewn into them, so that all of the speech in the child’s environment was recorded. Twenty of the families were White and twenty were Black. In each racial group, half of the families were middle class and the other half were of lower socioeconomic status. The children were between 4 ½ and 5 years of age. Half were male, and half were female.

Recordings were made across various situations spanning a normal day, including time at home before school, time spent in school, and after-school activities up to bedtime. The basic data were all taken from naturally occurring conversations. The tapes of these conversations were meticulously transcribed and then put into a database that contained all of the raw data in written, as well as spoken, form.

Overall, the results revealed no differences in the number of opportunities that young children had to talk at home. However, there were certainly differences in the amounts and variety of talk that was occurring at home and at school as well. Table 1 (reproduced in text format below) provides a summary of the total number of words taken during two different 15-minute samples of talk at home and in the classroom.

Table 1. Mean Total Number of Total Words in Adult Speech

Middle Class Black Parent: 78,412 Teacher: 30,297

Middle Class White Parent: 81,273 Teacher: 28,931

Lower Class Black Parent: 32,958 Teacher: 22,460

Lower Class White Parent: 72,727 Teacher: 38,990

The clearest result from comparing volume of adult talk across settings and groups is that the poor Black children hear less total talk — not only at home, but also at school. A combination of being Black and being poor, thus, reduces the overall level of talk. There may be a class difference: the White middle class children who heard a larger amount of talk at home, heard less than their working class peers at school.

The same pattern appears when the measure of language environment was the number of different words the children were hearing. Once again, the combination of being Black AND poor makes its appearance. Yet again, this was the group with the least language experience in the classrooms. These numbers are in Table 2 (reproduced in text format below).

Table 2. Mean Total Number of Different Words in Adult Speech

Middle Class Black Parent: 4,132 Teacher: 2,076

Middle Class White Parent: 4,004 Teacher: 1,810

Lower Class Black Parent: 2,140 Teacher: 1,615

Lower Class White Parent: 3,670 Teacher: 2,382

Hall and his colleagues pursued the implications of this work in many directions, particularly in relation to the design of assessment instruments to measure children’s progress in learning to read. For example, Hall and his colleagues conducted an analysis of the relationship between the words that appear on vocabulary assessment tasks and the words that the children heard at home and school. Their results showed that the school communicative environments of children from different social class and ethnic backgrounds did not differ in any significant way. There were actually fewer such words used in school in the sampling periods than at home. School talk is school talk. But the home environments did differ along social class lines. Most notably, the discrepancy was once again greatest for children who were poor and Black (see Table 3 below).

Table 3. Mean Number of Vocabulary Assessment Words Produced by Significant Adults Broken Down by Race and Class

Middle Class Black Parent: 17.89 Teacher: 12.11

Middle Class White Parent: 21.11 Teacher: 11.44

Lower Class Black Parent: 10.55 Teacher: 12.00

Lower Class White Parent: 17.67 Teacher: 12.89

Once again, the combination of being Black AND poor made its appearance. This, again, was the group with the least language experience in the classrooms. This research provided answers to the main research questions:

Is the vocabulary used in creating readability formulas equally represented in the different social-class/ethnic groups?

Do the words used in various IQ tests appear equally often in the vocabularies of the different groups being tested?

The answer was a clear NO. Based upon their analyses, Hall and his colleagues asserted that existing reading formula designers “unintentionally but effectively build class and race bias into their lists” (Hall, Cole, Reder & McNamee [Dowley], 1977, p. 478). One of the effects of this bias is that poor Black children are confronted with a more difficult task in learning to read because they are learning with a relatively unfamiliar vocabulary. As a consequence, Hall et al. conclude, “If curricula are not changed, we must at least be aware that we are demanding much more of those children whose lives are not represented in the materials they use in school” (p. 479).

There is a strong conceptual relationship between these results on language use and the earlier mentioned research on memory and classification. By using norms from “the population at large” to construct psychological tests or reading formulas, psychologists slip an insidious bias into their attempts to assess academic ability and to organize instruction to help those children who are struggling. Instead of contributing to closure of “the achievement gap,” standard operating procedures exacerbate the very problems they are supposed to solve. As was the case for the experimental work on categorization and recall, tests of reading drew deferentially on possible vocabulary knowledge in a manner that the conflated background knowledge and reading skill.

A Common Focus: Ecological Validity

No matter the direction from which we approach the problem of comparative research on cognitive development, we repeatedly came up against the same, seemingly intractable issue. Whether dealing with questions of schooling’s influence in creating a “5-7 shift” or seeking to determine if people literate in Vai acquire new cognitive abilities that generalize beyond ability to read and comprehend text, the question of how assessment tasks fit into the life world of the person being evaluated would not go away.

In posing the issue in this way, there was a subtle shift in our thinking. At first, our position with respect to “test findings” was at best skeptical. We found that in the case of factors such as familiarity of the to-be-learned materials, the subtleties of experimental arrangements mattered. However, there was something missing. At best, we could stay unconvinced and bend our efforts to “overturning” some purported facts. However, the problem we faced was deeper. Raising doubts alone does little to advance knowledge. Therefore, we sought a more positive approach that could open up new domains of inquiry in a constructive way (for a discussion of various approaches under consideration, see Cole and Means, 1986).

Sylvia Scribner characterized the problem from the experimental side as needing to “locate” the experiment. Viewed from the perspective of the socio-cultural world within which the experiment is presumably “located,” this issue was referred to as one of ecological validity. We turn to this concept in Chapter 4: The Cognitive Analysis of Behavior in Activity.

Chapter Three Compositors: Michael Cole, Joe Glick, Ray McDermott, and Lois Holzman

Back to Section Two Introduction

Forward to Chapter Four