In 2003, a group of LCHC participants began to work with teachers and children to design and study a form of child-adult play called Playworlds [1]. Playworlds are a relatively new form of play that can be described as combinations of adult forms of creative imagination (art, science, etc.), which require extensive real life experience, with children’s forms of creative imagination (play), which require the embodiment of ideas and emotions in the material world (Vygtosky’s “pivot”). The development of both children and adults in this intergenerational hybrid form of play has been a central interest to playworld researchers.

LCHC playworlds have tended to look, in many ways, like Nordic playworlds. This is because they evolved from student and scholar exchanges with Pentti Hakkarainen’s laboratory in Finland, named Silmu, at the University of Oulu. In Silmu and at LCHC playworlds, children and adults bring a piece of children’s literature to life through scripted and improvisational performance, costume and set design, as well as multimodal rehearsal and reflection.

The LCHC playworlds did not come about to study a particular phenomenon or to answer a particular question. Rather, in 2003, there was a coincidental convergence of people at LCHC who had been working in and studying Fifth Dimensions (5thDs), all of whom were particularly interested in play, art, and the creativity of young children as culture producers. Many of these visiting scholars, graduate students, and post-doctoral researchers were coming to LCHC from outside the academy, where they had worked closely with young children as early childhood teachers or as therapists. Others had worked primarily as researchers, but were committed to uniquely collaborative modes of research/teaching with preschool teachers.

This group of researchers decided to see what would happen if we imported Gunilla Lindqvist’s (1995) creative pedagogy of play, a key component of which is playworlds, into the US. Several of us had recently observed Lindqvist-inspired playworlds at Silmu. Lindqvist, the designer of the first playworlds in Sweden and the author who coined the term, intrigued us because she reinterprets Vygotsky’s theory of play to argue that children’s play is an early form of the artistic and scientific endeavors of adulthood. Therefor, children’s play produces new and intrinsically valuable insights — insights that can be of value to adults and children alike. This view is not found in contemporary Western European and American biological, psychoanalytic, cognitive-developmental and cross-cultural psychological theories of play, nor in most preschool and early childhood therapy practice (Nilsson and Ferholt, 2014).

The first LCHC playworld, the “Baba Yaga playworld,” took place with four- to five-year-old children and their two teachers in a preschool over the course of four months. The second playworld, the “U.S. Narnia playworld,” took place with five- to seven-year-old children and their teacher in an elementary school on a military base over the course of 14 months. The first playworld made possible the second, and several different studies emerged from this second project, covering topics including narrative development, methods for the study, of play and the chemistry of cognition and emotion constituting experience (perezhivanie).

LCHC playworlds then continued in Sweden when Monica and Beth conducted a playworld project to study the meeting of playworlds with the work of three Swedish preschools that were inspired by the Italian Reggio Emilia Approach, and also new ways of conceiving of play in relation to learning. This project took place at Jonkoping University and the HallonEtt preschools in 2013-2014, and this project led in turn to several grant applications for continued playworlds research in Sweden. These proposed research projects would tackle issues such as the role of aesthetics in early childhood education, international “learnification” (Biesta, 2006) of Early Childhood Education, and ways to use playworlds focused on food and eating to help the many child refugees who are new arrivals in Swedish preschools.

Robert and Monica are now both at Jonkoping University, which has generously supported this Swedish playworlds research, but Beth, Sonja, Anna, and Kiyo have been co-writing the research project applications, thus continuing the LCHC tradition of international research. These collaborations have been made possible by each of our continuing work with playworlds since our times working together at LCHC, but also by the fact that our initial playworld research at LCHC remains notably emotionally alive today for all of the 2003-2005 playworld participants, researchers, as well as teachers. The early LCHC playworlds replicated some of the characteristics of playworlds in the research teams, where intergenerational team of researchers worked together as witches who ate humans and learned how to swim, lost and lying children, heroic siblings, and hedgehogs.

Engaging in Playworlds evoked intense emotions and new ways of thinking in all of the participants, and the subsequent ways in which we acted toward each other were often carried back to the laboratory. Methodologically, through our ongoing playworld collaboration we are “bridg[ing] segregated and differently valued knowledges, [and] drawing together legitimated as well as subjugated modes of inquiry” (Conquergood, 2002, p.151-152). By integrating the knowledge acquired in the playworlds with knowledge we brought from the social sciences and our human experience, we brought back into conversation the excluded knowledge, knowers and means of knowing of childhood (Ferholt, 2010; Ferholt et al., forthcoming.)

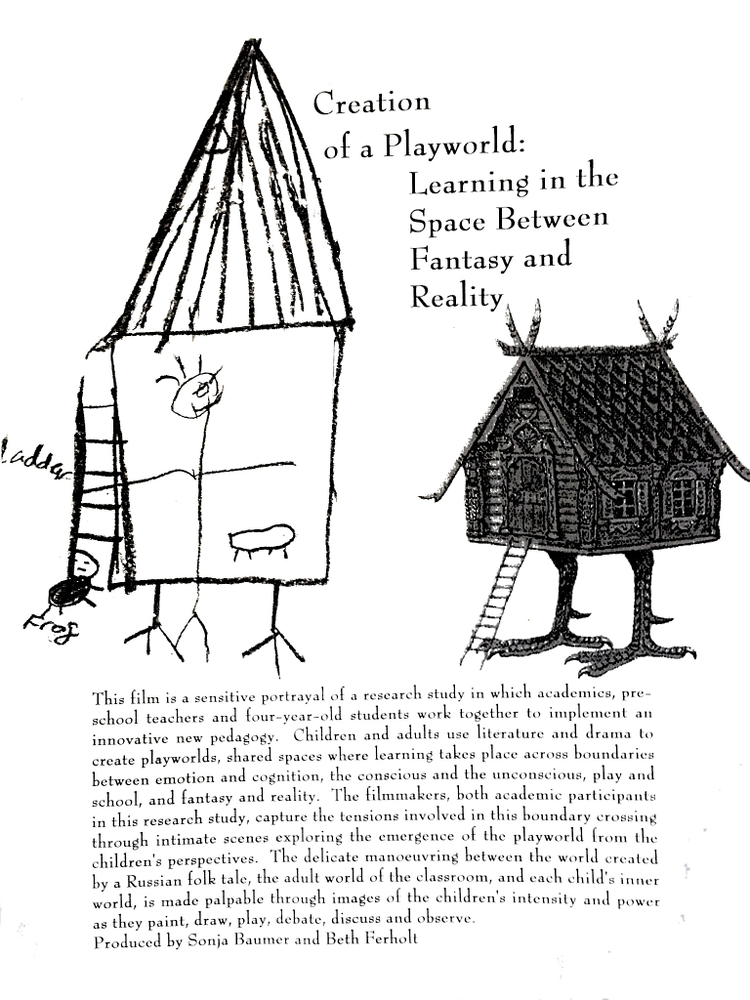

The Baba Yaga Playworld

The Baba Yaga playworld was based in many versions of the Baba Yaga folk tale about a witch who lives in a hut with chicken legs. We merged these versions of the tale into a single power point document, which we displayed on the wall and which was read aloud by a character that was the “narrator” of the playworld. The researchers came to the classroom once a week, at first just to talk, draw and play with the children. Later, they came in costume to act out various portions of the composite Baba Yaga tale. The acting sessions began with scenes that were more scripted, in which the children participated only as audience members, and they culminated with an acting session during which the adults, who were in role, invited the children into the story. After acting sessions, there were related projects that were guided but fairly open ended, such as painting and drawing the events of the day, making small huts-with-chicken-legs sculptures, painting the actual hut without its chicken legs, etc. As the semester progressed, the children began to work with those characters that were played by adults to bring the story to its conclusion, i.e. to save the hedgehog from becoming Baba Yaga’s stew.

After the adult acting portion of the project had finished, the children began to play the Baba Yaga stories with intense engagement, and to invite the adult participants into their play scenarios. The children’s teachers were not participants in this playworld, so these invitations took place only during the researchers’ weekly visits to the classroom. For the rest of the week, the children played without adults. At this point in the project, we sensed that there was great opportunity for the children to develop the playworld, but the teachers decided that the project was over.

Several aspects of the Baba Yaga playworld interested us, but there was not enough data gathered in response to any given question to allow us to generate well grounded conclusions. So we began to design a project that would allow for the investigation of the following aspects of playworlds. We examined the development of a close-knit community of children in the classroom and the role of gesture in this knitting process. The children in the Baba Yaga projects appeared to develop an increased awareness of each other such as looking out for each other when they became scared of Baba Yaga or were having trouble expressing themselves, etc. They were often imitating the stomping of Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut (the hut that had appeared in person in their classroom during the playworld, see video clip above). Both the children and the adults appeared to be markedly emotionally involved in the playworld. The children who were having the most difficulties according to the teachers (for instance a child who spoke almost not at all and a child who disrupted the class very often), appeared to be most engaged in the playworld and also appeared to overcome some of their teacher-identified “difficult” behaviors in the playworld.

There were instances during the playworld when the ethical responsibility of the researchers and teachers came to the fore, in this case when one child began to have nightmares about the hut on chicken legs, and the one American researcher wondered if the researchers had “scared” this child. We also began to think that it was through the making of a film of the playworld for an outside audience that many of these most interesting aspects of the playworld came to our attention. For example, editing the film for aesthetic results appeared to increase communication between researchers, and increase understanding, of some key elements of the playworld.

A concrete result of the Baba Yaga playworld was the formation of the International Playworld Network (IPWN). The IPWNW is an organized group of playworld scholars who have now been collaborating in their playworld research, through joint conference presentations and playworld conferences as well as though our international research projects, for over two decades. These scholar’s work, and the playworlds that have been the focus of their studies, including the LCHC playworlds, are discussed on the Playworlds Web Page.

The Narnia Playworld

The US Narnia playworld was designed to respond to some of the questions that arose, but were unanswered, in the Baba Yaga playworld. The first priority of the researchers was to find a US setting that could tolerate a playworld that would continue until the child participants wanted it to end, or until the end of the school year, whichever came first. The site that was chosen was the classroom of one teacher, a visual artist who had been teaching in public elementary schools on a US military base.

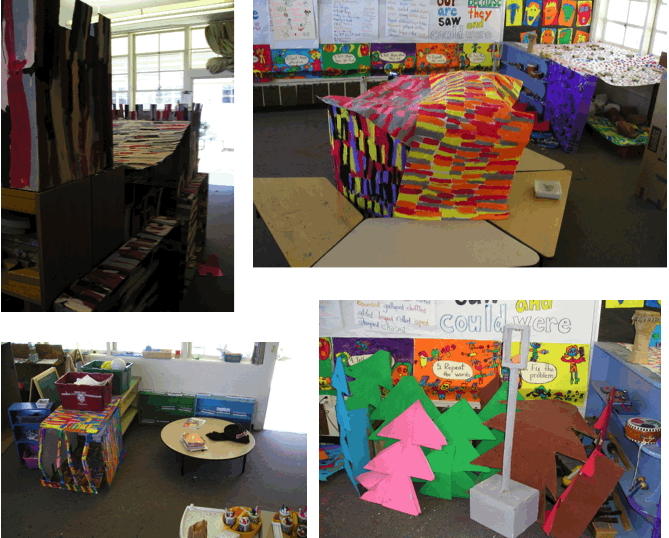

In the US Narnia playworld, the first half of the novel was read aloud to the children before the acting began, but the second half of the novel was never read to the children. Instead, over the course of the project, the children became more active participants, collectively writing and directing their own resolutions to the novel’s central conflicts. Over the one-year period during which the playworld took place, some or all of the participants enacted parts of the novel in 14 playworld sessions. Following the enactments, the students, researchers and teacher engaged in group discussion, followed by free play and/or art activities.

Most of these 14 sessions included all four researchers, who played the child heroes of the playworld. The teacher joined during the seventh of these sessions, playing the evil White Witch, and the children joined during the eighth of these sessions, as themselves. For the final of these sessions, the children were the primary planners of the adult-child joint play.

All of these playworld sessions involved set pieces and props created by both the adults and children, including some props that were designed to appeal to the participants’ senses of touch, smell and sound. By the time that half of these sessions were completed, the teacher, who had been moving the set pieces to the side of the classroom at the end of each playworld session, began to leave the set pieces in place throughout the week. The classroom was filled with the large, colorful structures, and the teacher conducted all of his classroom activities in and around a cardboard dam, cave, castle, etc.

After the final session of adult-child joint acting, the children decided to present a play of the playworld to their families. This initiated a series of child-conceived sessions which were unanticipated by the adults. Their teacher, with some input from one of the researchers, helped the children to design, direct and rehearse this play. The time the class spent on this process continued to grow until it was taking whole days and crowding out other scheduled activities. The children presented the play to their parents in the final week of the school year. After the school year was complete, the adults continued the playworld through many different forms of playful analysis, including adult-adult interaction that incorporated filming, drawing and painting.

Whereas the Baba Yaga playworld research project data included only audio and video recordings of the acting, art activities, and field notes by the research participants, the US Narnia playworld project combined a pre- and post-test quasi-experimental design with participant-observer ethnography. Ethnographic data included field notes, audio and video recordings, interviews, and email correspondence. Field notes were written after each site visit by the four participating researchers and by an external observer. The teacher also wrote field notes. Audio and video recordings were made of all playworld sessions and of all interviews.

Data analysis of ethnographic data included two types of analysis: analysis of discourse and communicative exchanges using transcriptions from the video and audio recordings and the juxtaposition of the material of a playworld with poetic representations of this playworld (Ferholt, 2010). These second methods of analysis merged with the design of the research project, collection and analysis of the data, and presentation of the findings. Furthermore, in as far as collaboration with the teacher included ongoing researcher-teacher joint analysis in a form that mimics the playworld, the playworld itself can be described as having still been in progress through this second method of analysis.

Evidence from the US Narnia playworld that has been analyzed to date demonstrates that participation in a playworld improves children’s narrative and literacy skills (Baumer et al., 2005) and that playworlds can lead to the socio-emotional development of both adults and children (Ferholt, 2009; Ferholt & Lecusay, 2010 (This paper presented with examples from the video data). Analysis of this data has also been used to expand Vygotsky’s concept of the “zone of proximal development” to include development of adults participating in the zone with the child (Ferholt & Lecusay, 2010).

Cross-cultural projects that involved the US Narnia playworld data include a study of imagination and the use of psychological tools in playworlds that were created in different countries but were based in the same work of literature (Hakkarainen & Ferholt, 2012), and collaborative analysis of agency and engagement in a US playworld (Ferholt & Rainio, 2015).

Work in progress also focuses on the fact that US playworlds have provided unique evidence of the synergy between emotion and cognition, a notoriously difficult process to study, but also one recognized to be of central importance to cognitive and social development. This work includes a study of perezhivanie in the US Narnia playworld (Ferholt, 2009; Ferholt, 2015; Ferholt & Nilsson, 2016a; Ferholt & Nilsson, 2016b). Details of these materials and links to the authors are available on the Playworlds Web Page.

Chapter Compositors: Beth Ferholt and Robert Lecusay

[1] This group consisted of Sonja Baumer, Beth Ferholt, Kiyotaka Miyazaki, Monical Nilsson and Anna Rainio, who were joined by Robert Lecusay, Lars Larson, Kelli Moore and many others.

Back to Chapter 13

Forward to Chapter 15